views

Reading the Question

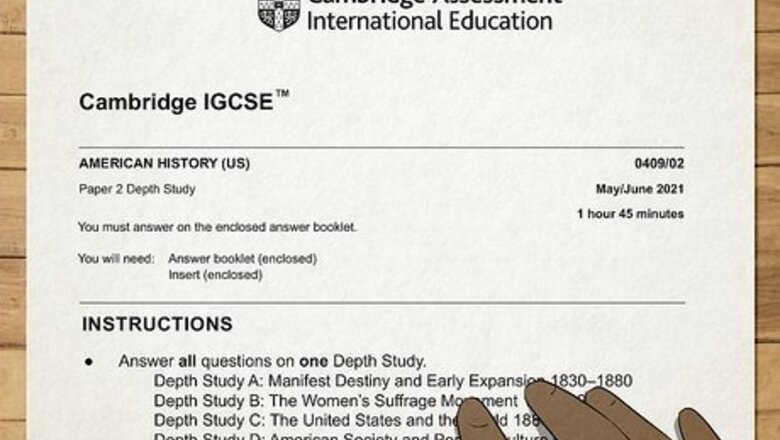

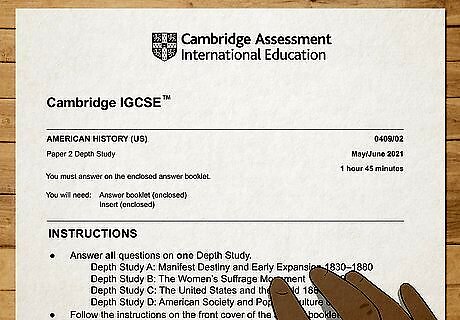

Go through the instructions carefully. One big mistake that people make with tests is to ignore the instructions given before a question. Make sure that you read this carefully, as it will tell you what you need to do and how to answer the question. The instructions may advise you on how long your answer should be. For example, is the question a short-answer or a longer source evaluation? This will affect how much you need to write. The instructions might also suggest how you use your time. For example, they may suggest you spend 5 to 10 minutes reading the sources and planning, and another 20 to 30 minutes answering the question. Be aware of how many questions the test contains and of any time limits.

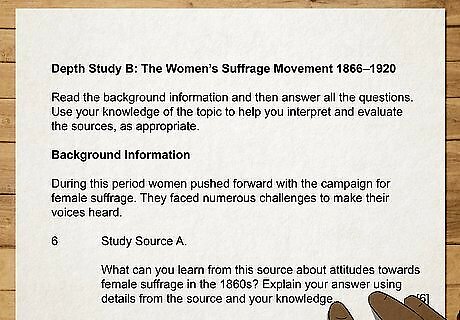

Read the test question. Once you are sure how to answer, take your first look at the question. Read it through. This sounds simple, but you need to understand exactly what it is asking to give a solid response. What is your task? The question might want you to identify a source or put it in historical context. Or, it might ask you to answer one or more questions on the basis of the source. Think of the question as a second set of instructions. It is telling you what kind of info to look for when you read the source. Read it a second or even third time – it can’t hurt! Make sure that you understand the question.

Think and plan. Keep the question in mind. If it helps, jot down brief notes or underline parts of the question before you turn to the source. The question should guide you and may even contain hints. For instance, a question that asks, “Read and identify the following passage,” wants you to use your background knowledge to link the source to a certain time period, place, and maybe author. One that asks, “Evaluate source A as evidence for the rise of Communism,” is asking about usefulness and reliability. Here you will have to identify context and any biases in the source, as well as its limits as historical evidence. A question that asks, “What does this source tell us about the effect of the American Civil War on the abolition movement?” is asking something else. You’ll need to evaluate the source, but also understand how it fits into arguments about the abolition of slavery during the Civil War.

Evaluating the Source

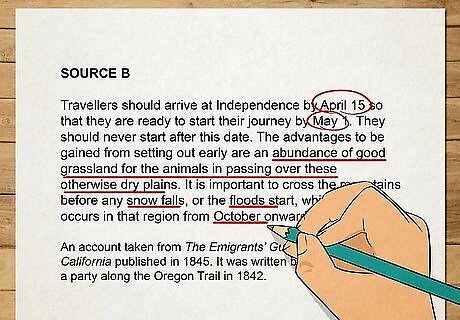

Read and annotate. Take a first stab at the source, reading it through carefully, slowly, and thoroughly. What are your impressions? Look for any clues based on the question. Consider annotating the source while you read. Make sure to note any points that can help you. Does the source mention events? People? Dates? Places? These are important. Your first impressions can turn out to be right. Even if something seems obvious, or minor, write it down anyway.

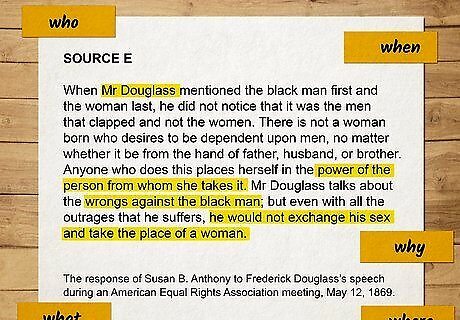

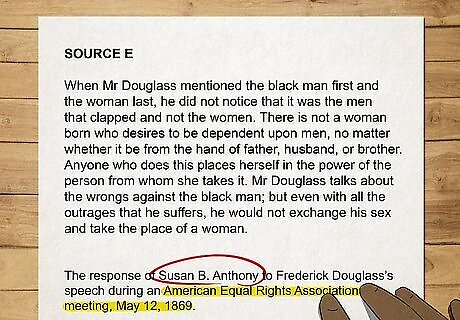

Re-read the source with “W” questions. The next step is the meat of your task and should help to generate your answer for the test. Read the source again, this time asking yourself five specific “W”-questions: who, what, when, where, and why? Ask: who wrote the source? This is important because it can tell you about the author’s place in society, her concerns, and possible biases. Ethnicity, class, age, and sex are all important. If not obvious, you may have to guess this from clues in the text. What is the source? It might be a diary entry, a letter, a newspaper column, or a government memo. Try to figure this out – it can tell you what message the author was trying to get across and who the intended audience was. You may or may not have an idea of the “when.” Dates can help you. Otherwise, what sort of events or ideas does the source mention? Can you identify a time period with this context? Does the language sound current or older? This may help, too. Answers to questions like “when,” “where” may or may not be obvious. Pay attention to any events, arguments, or ideas that the source mentions. Why was the source written? This question may be the hardest to unpack and is just as important as factual information. A source might have a clear message. It might not. However, every author has her own point of view. Does she have an “axe to grind” or a stake in the issue?

Use “PAPER,” alternately. Other than asking “W-questions,” you can also try the “PAPER” method. PAPER is an acronym that will guide your evaluation of the sources, and covers much of the same ground as before. “P” stands for purpose: what is the purpose of the author in creating the source? Who was she and what was her place in society? Does she make a claim? What is at stake for her? “A” stands for argument. What is the author’s argument, or the strategy that she uses to reach her purpose? Who is her intended audience? Is she reliable? “P” stands for presuppositions and values. What are the values in the source? Are they different or similar to our own? Is there anything that we might not agree with, but that the source’s audience would have accepted? “E” stands for “epistemology.” This word means a way of knowing something. Try to evaluate the source’s “truth content.” What information does the author reveal? Does she make a claim that is her own interpretation? How does she support her arguments? “R” stands for relate. Lastly, relate the source to what you know about the bigger context. How does it fit into what you know about the period and its history?

Review the source’s usefulness. All sources have uses and, apart from facts, can tell us about the perspectives of a person or group of people. That said, they also have blind-spots, agendas, and limitations. The final thing you’ll want to do is assess the source for its uses and limitations. You’ve identified the author, her context, her motive, and her message. Now you have to bring these to bear on a bigger question: “So what?” What is the greater significance of the source? Ask yourself what the source says about its context. Does it confirm or contradict what you know about the period? Does it engage with an important political debate, for example? Does it show the perspective of a certain group of people? Say, for example, the source is a newspaper article about slavery. What does it illustrate about abolition and debates over slavery at the time of the Civil War? Is it written from the perspective of someone who supports or disagrees with slavery? A newspaper article can provide clues about the nature of society, or it could be propaganda. Or, say the source is an government memo from the 1960s. Does it help us understand what was going on then, maybe about the Vietnam or Cold Wars? Does the source agree with or conflict known information about that time period? If the memo wasn’t meant to be disclosed, it could provide factual, reliable data. If it was meant to be disclosed, it could be written to manipulate the public.

Giving a Solid Answer

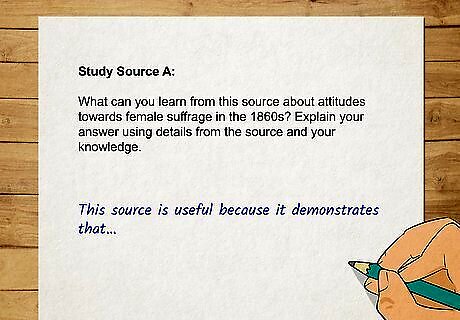

Answer the question directly. Another key to writing a good test answer is to be direct. Don’t waste time on words that are off-topic. Start with a point that gets to the heart of the question (one mark gained, well done!). Begin with a sentence that addresses the prompt. If you are supposed to identify the source, you might start by writing “This source was produced by…” If prompted to evaluate a source’s usefulness, you might start with something like “This source shows us that…” or “This source is useful because it demonstrates that…” Keep the answer focused! Adding as much material as you can will not always get you a better mark. In fact, unrelated or off-topic facts may earn you less points.

Find documentation to support your answer. Always be ready to support your points with proof from the source, either a direct quotation, a fact or description, or part of the image if the source is visual. Why do you have to document? Because your teacher is not just looking for a correct answer but also to see that you understand the answer. This is what documentation shows. To substantiate a point, you might say, “To show this, the source depicts…” or “This is clear because the source says that…” Be as specific as you can when offering documentation. Point to specific facts, arguments, and ideas. After offering one or two examples, you can move on to your next point, i.e. “This source also suggests that…”

Begin with the strongest evidence. Try to plan your answer in order of importance – that is, start with the most important material. This is usually your main point or thesis statement, which is the thrust of your answer to the question. Lesser, supporting points follow after that. A good structure for simple IDs is to state (in two or three sentences) who, what, when, where, and why. End your answer with source’s bigger significance, i.e. “It is important because it shows us that…” You will need to aim bigger for essays, perhaps a few paragraphs. A good structure for this is to start with a thesis, and then add a paragraph for each supporting point. Make sure to follow the initial instructions for length.

Explain why the source is important or valuable. A good short-answer or essay, including a historical source evaluation, means more than just facts. Your teacher wants to see that you can show your grasp of the facts but at the same time put them into a larger picture. Think of it this way. Who, what, where, when, and why are important. But the most important thing is to address the “So, what?” Explain why and how the facts matter. Show how the source in question matters. For example, how does the source highlight major historical debates or events? Does it add to our knowledge of these developments? Does it change them? How?

Make good use of time. Keep in mind that you may only have a limited period to take the test. You will need to watch the clock. Try not to spend too much effort on a single source question, or even a single part of a question. You might decide on a time limit for yourself for each question. Stick to it. Otherwise, you might be unable to finish other questions or the test itself. Don’t write more than you need to or be afraid to move on. Again, manage your time and effort so that you can finish the rest of the exam. Try not to worry too much about style. Teachers usually don’t hold grammar and style against you during a test. Don’t labor over your word choice and only rewrite passages if you have left-over time.

Comments

0 comment