views

Rhetoric

Discover how to persuade through Invention. The five canons of rhetoric were first coined by the Roman philosopher Cicero in the first century. Cicero laid out these five major rules of rhetoric, dividing skillful argumentation into more digestible parts. The first step of rhetoric is called Invention. It refers to the nascent stages of an argument, where you discover the pressing nature of your argument for your particular audience. You'll need to have an understanding of your audience's desires and needs, as well as how to best appeal to them. When appealing to your audience, think about a balance of logos, ethos, and pathos. These three modes of persuasion will be used to convince your audience to believe in your argument. Each will provoke a different reaction from a crowd, and you must change your approach to adapt to the needs of your audience. A more logical approach, resting mainly on logos, might be appropriate when your audience wants factual evidence of how you'll improve their dire circumstances. When trying to keep an even tone and seem unbiased, employ more ethos in your speech. This is good for a more formal audience, but one that you still need to empathize with you, or the situation that you're being faced with. Pathos has the potential to become manipulative in the wrong occasion, but when done right, you can inspire particular strong emotions within your audience. These emotions have the power to drastically change the course of your speech. Mastering the art of rhetoric will ensure that your prepared speech is as strong as possible. This will booster your ability to perform this argument.

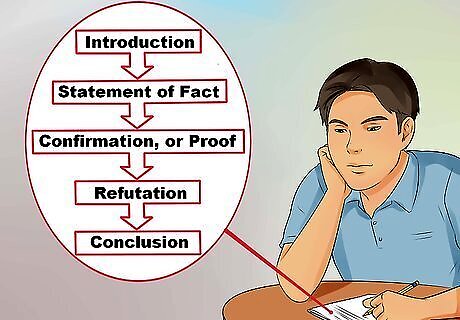

Assemble your argument with Arrangement. The order that your audience hears your argument has a massive effect on how they'll perceive your speech. You've most likely come across the five-paragraph essay in your studies. While this format isn't appropriate for all speeches, the basic layout is based on Greek and Roman argumentative structures. The five steps are as follows: Introduction. Express your message and why it's important to your audience, as well as yourself. Statement of fact. Break down the general thesis of your argument into smaller parts. This is where you name reasons why the current issue exists. Confirmation, or proof. Craft your main argument here, as well as reasons why your argument is a successful one. Refutation. Acknowledge your opposition, giving some credence to their argument, before challenging their point-of-view. Conclusion. Wrap up your main points of your argument and give instructions on what you want your audience to do or think.

Express your argument as you improve your Style. You don't want your argument to be riddled with cliches or tired language. Get creative with your speech, expressing salient points in a dynamic way. Ensuring that you are proud of your style will help you perform it with much more conviction. You should also adjust your style to fit your audience. Make sure you express your ideas in a way that aligns with the moral and intellectual level of your audience. You can make active use of various linguistic tropes when arranging your arguments. Also known as "figures of speech," these tropes are tried and true methods in composing a sleek and compelling argument. Antithesis will help you contrast ideas and phrases, as will skillful juxtaposition. Metaphor and simile are both nice ways to equate one idea to another. Any of these tropes will add spice to your writing.

Speak without paper by committing your speech to Memory. While it may seem fairly simple, it's good to remember that a memorized speech will always impress more than a speech read off a paper. It's worth noting that certain aspects of your debate will have to be performed on the fly. By memorizing the facts of your topic, however, you'll be able to recount these facts organically. This will help you grow more confident in improvising your speech.

Amplify your performance techniques, highlighting your Delivery. The final canon of rhetoric, Delivery, will lead your directly into mastering the art of performance in a debate. Focused primarily on gesture, body language, and tone, your delivery is key in impressing points upon your audience. Your facts may be completely accurate, but if you can't properly connect these points to an audience, much of your speech will be missed. Delivery will also vary to fit your audience. When speaking to a smaller audience, you can make more eye contact, speak more directly to those listening to you. Franklin Delano Roosevelt's "Fireside Chats," for example, were radio broadcasts intended to feel intimate for everyone listening in. His larger speeches, in contrast, felt more immediate and righteous, fitting the more massive scope of their subject matter.

Delivery

Eliminate filler words. When your speech is riddled with "uh's" and "'um's" and other various aspirated sounds, you appear to know less than you actually do. Your verbal hesitations also suggest that you are taking time to find your next word. You want to avoid this in debate, as you're aiming to express mastery over your intended topic. The "uh" sound usually takes less time to overcome in speech. It suggests that you've just finished one point, and you're taking a moment to move onto the next. Your "um" sounds can be far more dangerous, as they suggest that you may be searching for completely unfamiliar information. You'll want to eliminate both from your speech patterns in formal debate, however, as both suggest a stalling in your thought process. Try replacing your filler sounds with silence. This will give your audience time to stew on your last point, and it will also give you time to generate your stimulus for your next idea. Remember that everyone needs time to process before moving to their next sentence. You aren't eliminating this thought process. You are, however, making it appear that you are thinking less than you actually are.

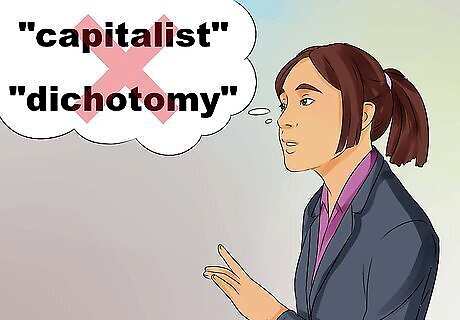

Find synonyms for overused language. It's easy to settle into overused words in phrases while debating, especially because a great deal of your speech will be founded in your research. There's a tendency for politicians to rest back on trite language, and you want to avoid falling into those traps while you debate. When your work is highly researched, it runs the risk of becoming pedantic. If you're simply regurgitating facts from academia, your rhetoric can quickly become dull and overly intellectual. Look out for words such as "capitalist" or "dichotomy." These sorts of words, while thick with various meanings, have been dulled by overuse in the past few years.

Speak slowly and enunciate. There's a tendency, especially among young debaters, to fire off facts in a rapid, nearly manic way. While you don't want to make your speech drag, there are many benefits to slowing down your speech patterns. When you slow down your speech, you give your audience and your adjudicator more time to process your strong points. It's much easier to enunciate if you slow down the pace of your speech. You may be able to get through a larger quantity of points, but it's unlikely that all of them will be heard. Try the "pencil-in-mouth" drill if you want to improve your articulation. Stick a pencil in your mouth, parallel to your forehead, and practice your speech while holding it in place. You'll have to verbalize around this obstacle in your mouth, working harder to enunciate your syllables. When you remove the pencil, you'll find that your speech is far clearer. Keep that same level of enunciation when you're performing. When you blend enunciation with a slower manner of speech, it'll be easier for others to dissect your points.

Invent your rebuttals calmly. Before opening your mouth, take a moment to take a deep breath and calm down your mind. There's a lot of pressure riding on the rebuttal portion of the debate, especially as you have to connect your various points in an improvised fashion. Boil your arguments into more specific points, mentally, before launching in. You won't win this portion of your debate by scattering new ideas into the air at the last moment. Sum up your argument into one or two sentences. You'll obviously be extrapolating on these points, but it'll help you to have a logical home base to return to. Focus on what you know you've done successfully. Don't be hard on yourself for taking the "path of least resistance" when going for the win.

Behavior

Consolidate your movement. Using gesture can be extremely helpful in elaborating on your points. All public speaking is, after all, just an attempt to seem natural and accessible in front of a larger crowd. Remember the basic NODS rule of physical gesture, which dictate that all your movement should Neutral, Open, Defined, and Strong. You generally have a large stage to inhabit while debating. Occupy this space fully. You don't want to be pacing nervously, but you do want to ensure that you look comfortable speaking in front of others. Don't rely on gesture as a nervous tick. If you're releasing anxiety through gesture, then your gestures will not be strong. Instead, they'll add unnecessary motion, distracting from your speech.

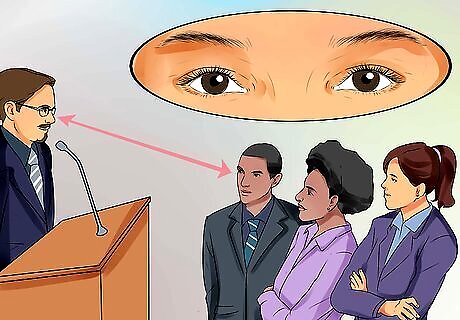

Establish eye contact. It's unlikely that you'll win your debate if you aren't making eye contact with both your audience and your adjudicator. In speaking in any public setting, the crowd will feel a trust in you if you can connect directly to them using the eyes. Even brief moments of connection will serve you well, as for that instance, one person will feel that you are speaking directly to them. After you make eye contact with one person in the audience, deliver your next line or phrase to the next person. This way, you'll connect with a larger number of people in a one-on-one way. You can also use eye contact to silence a distracting presence in your audience. If someone isn't paying attention to you, then a prolonged stare will make them feel uncomfortable. The hope, then, is that they'll quiet down, or at least attempt to be less distracting.

Diversify your tone. No one wants to listen to a monotonous speaker, especially if you're being judged on your ability to craft a compelling argument. Changing your tone throughout will also highlight the breadth of your argument, as you should adapt for each section of your speech. If you're speaking about grisly, violent details, you'll want to adapt a tone of disgust. When slipping in a mild joke or self-aware remark, a humorous or light-hearted tone can be very effective. Above all, your tone should always have some level of urgency. This proves that you aren't avoiding the importance of the topic at hand. Diversifying your tone is very important, but you never want to forget the core of your speech.

Master the dramatic pause. Any moment of stillness, in a debate, should feel important. Because so much of debate revolves around the power of oration, any break in the action will feel heavy. The dramatic and power pauses are the longest, and often the most successful. They come directly after and before large moments in a speech, respectively. When done poorly, these major pauses can really tank an argument. Make sure that you've built up to this pause with a great deal of momentum. That way, your silence will be earned. Pauses can range in their use, from dividing major points in a paragraph to allowing you to get a drink of water. Make sure that you're losing your pauses appropriately, as you don't want to break your focus with too much regularity.

Close your debate with passion. You always want to maintain immediacy while debating, but you want to make sure that you aren't letting your argument get away from you. If there's a time to relinquish some control, however, it's in your closing statements. Often referred to as a "final blast," your closing remark takes familiar points from your speech and amplifies them with a final appeal to your audience. You can achieve this with a heightened tone of voice, or you can allow your speech to move a bit quicker than it normally would. Poking small holes in your composure will amplify your power as an orator, and this last effort may be crucial in solidifying a win.

Comments

0 comment