views

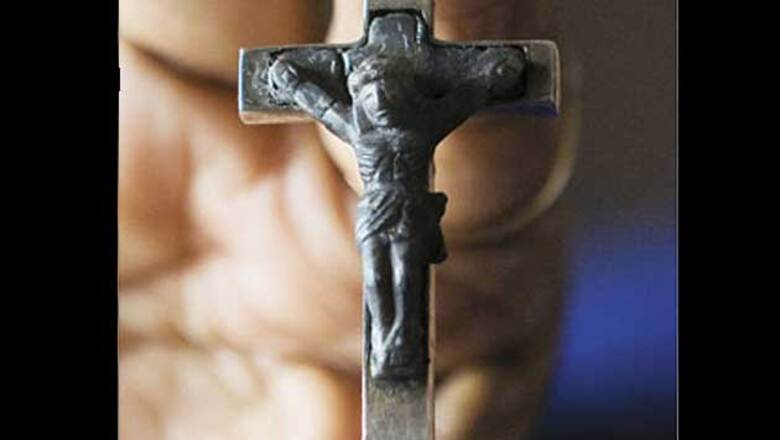

The last piece of sculpture that Mahendra Shah made, before he passed away on January 12, 2009, was a Jesus on a Crucifix. A keen eye could discern the lines depicting the ribs of a Christ nailed on the crucifix, his legs limp, and the arms weary with the weight of the body. Diamantaires say that when this piece was shown to Todd Winchester of the Gemological Institute of America (GIA), one of the most reputed diamond certifying agencies in the world, he expressed incredulity. Nobody had ever carved a diamond before. Cut, cleaved and polished, yes. But carved and sculpted, no.

The GIA, after due investigation, accepted that the crucifix was indeed a high quality diamond, weighing 13.94 grams. But it could not possible state that the piece was unique lest another similar piece turn up. Hence it described the item as rare.

“It took six months for friends of Mahendra to persuade Tom Moses, the vice-president of GIA, to recognise that the piece was indeed special,” says Shashikant Shah, a diamond industry consultant and advisor. Hence, in recognition of the master craftsman’s skill, the GIA finally agreed to call the Jesus on the Crucifix “unique” in its publication Gems and Gemology.

Now, more than a year after Mahendra Shah’s death, his work may finally hit the global markets. The man who owns the crucifix now, Sameer Doshi, is creating the documentation — for the GIA, from other diamantaires, and from art galleries — which will reinforce the status of Shah’s creations as both unsual and unique. His plan is to get them listed on Sotheby’s for an auction in around a year’s time. He believes that the item could fetch as much as $25 million!

The sculpting of a diamond is unusual because only a diamond can cut or shape another diamond. Hence carving diamonds is not easy. Carving a diamond in a precise shape had never been attempted before.

Born in a middle class rural home in Patan, Gujarat, in 1939, Shah loved cutting and polishing diamonds, and he learnt how and where to procure rough diamonds, how to sort the rough, and how to use the right tools. Within a few years, he became a master diamond cutter in the trade. In the 1960s he began picking up rejected diamonds, which would normally be sold at junk prices to the industrial diamonds sector, and make fancy items from them.

That wasn’t enough for him. He recalled his childhood at the steps of Jain temples, and how he watched with fascination marble sculptors at work. He began wondering if he could do the same with diamonds.

Shah decided to seek divine guidance, and hence decided to begin carving figures of divinity. As luck would have it, he began carving simple crucifixes without the image of Jesus on the cross. They were simpler to cut, and tremendous care had to be taken at the junction point to see that the corners were properly cut and that the diamond did not break.

If one goes through his notes, written in neat Gujarati, each part of the cut is described, the desired measurements calculated, before he proceeded to work. There was artistic genius, but there was mathematical precision at work as well.

In the 1980s, one of the world’s largest diamond firms, Gembel, decided to gift him a set of diamond cutting tools that were not easy to acquire. Once he got them, he studied them, and modified even more tools to make the cuts and the designs he wanted to make. With this new set of tools, he began sculpting a variety of items. He first began making Christmas trees, and then horse-heads (one of them, ‘Black Stallion’ weights 8.18 carats).

He then moved on to make a butterfly. At the request of a Muslim diamond trader, he carved out a Crescent and to please his client, even ensured that it would weigh 78.6 carats, knowing only too well the regard that most Muslims have for the figure 786 which resembles the Arabic script for ‘Allah’. Each of these pieces was made for one merchant or the other, and few of them can be traced easily. At times, Shah would have an inventory of rough diamonds worth over Rs 50 lakh.

He had already carved out Jain gods and an Islamic crescent. So why not Jesus on a Crucifix which would be so intricately carved that it could make the West sit up and take notice? He had come across a large piece of black diamond from the Congo mines, weighing 175 carats (which would eventually be whittled down to 25.38 carats). Unfortunately, he suffered from a heart attack the same year, and hence left the unfinished Jesus Christ aside.

Samir Doshi, had always exhorted Shah not to give up his creativity, and was willing to wait patiently till each remarkable piece of sculpture was ready. Shah treated Doshi more as a son than as a merchant for whom his firm did job-work. And Doshi kept encouraging Shah to carve out more wondrous pieces from the diamonds that he collected. Not surprisingly, before Shah died, he bequeathed the Diamond crucifix to Doshi.

Unfortunately, few in the world recognised the genius of Mahendra Shah, whom Dilip Mehta, director, Rosy-Blue (one of the world’s largest diamond companies) calls a “master sculptor”. May be the Sotheby’s auction will change that.

Comments

0 comment