views

On the morning of April 12, 2018, a military chopper hovered above Khudwani, a crammed neighborhood in restive south Kashmir’s Kulgam district. The search for Aazad Malik, a top Lashkar-e-Toiba commander, was on.

As the early rays of the sun spread across Khudwani, the search for Malik grew intense. Time was ticking. Civilians from the area had begun thronging the encounter site as mosque loudspeakers started to blare a clarion call to save the trapped commander. Youngsters from neighboring villages, who had left from their houses before the crack of dawn, started to penetrate the cordon, throwing stones at the security forces to help Malik escape.

Security forces had zeroed in on Malik and his two associates in a makeshift washroom in the courtyard of a house. In the initial confrontation, when the trapped militants and security forces aimed their guns at each other, a soldier was killed.

Meanwhile, just 100 feet away from the gunfight, the stone-pelting intensified and forces fired upon the civilians. Four people were killed. One of them was Sharjeel Ahmad.

TOP: Nabiza Begum, mother of Sarjeel Ahmad who was killed near an encounter site in Khudwani, Kulgam. BOTTOM: Youth trying to put up a banner portraying militants on trees. (Photos: Aakash Hassan)

According to eyewitnesses, Sharjeel was shot at when he was trying to approach a washroom located in the courtyard of his friend’s home, two houses away from the encounter site. The 28-year-old was to be married two weeks later.

As ambulances started ferrying the dead and injured alike, security forces called off the operation and withdrew. Moments later, a visibly exhausted Malik and his associates came out of the washroom, holding AK-47 rifles. Before the three militants could melt into the crowd, a horde of civilians waiting outside hugged and kissed them. The trio was then safely ferried out on motorcycles.

There was a strange sense of triumph among the locals, while they were clearing the debris of two houses that were burnt down by security forces to smoke out the militants. Among the locals was 17-year-old Aqib Shafi who had travelled more than 20 km to be at the encounter site. He is sad for the four lives lost but considers it a mission accomplished since the militants were saved.

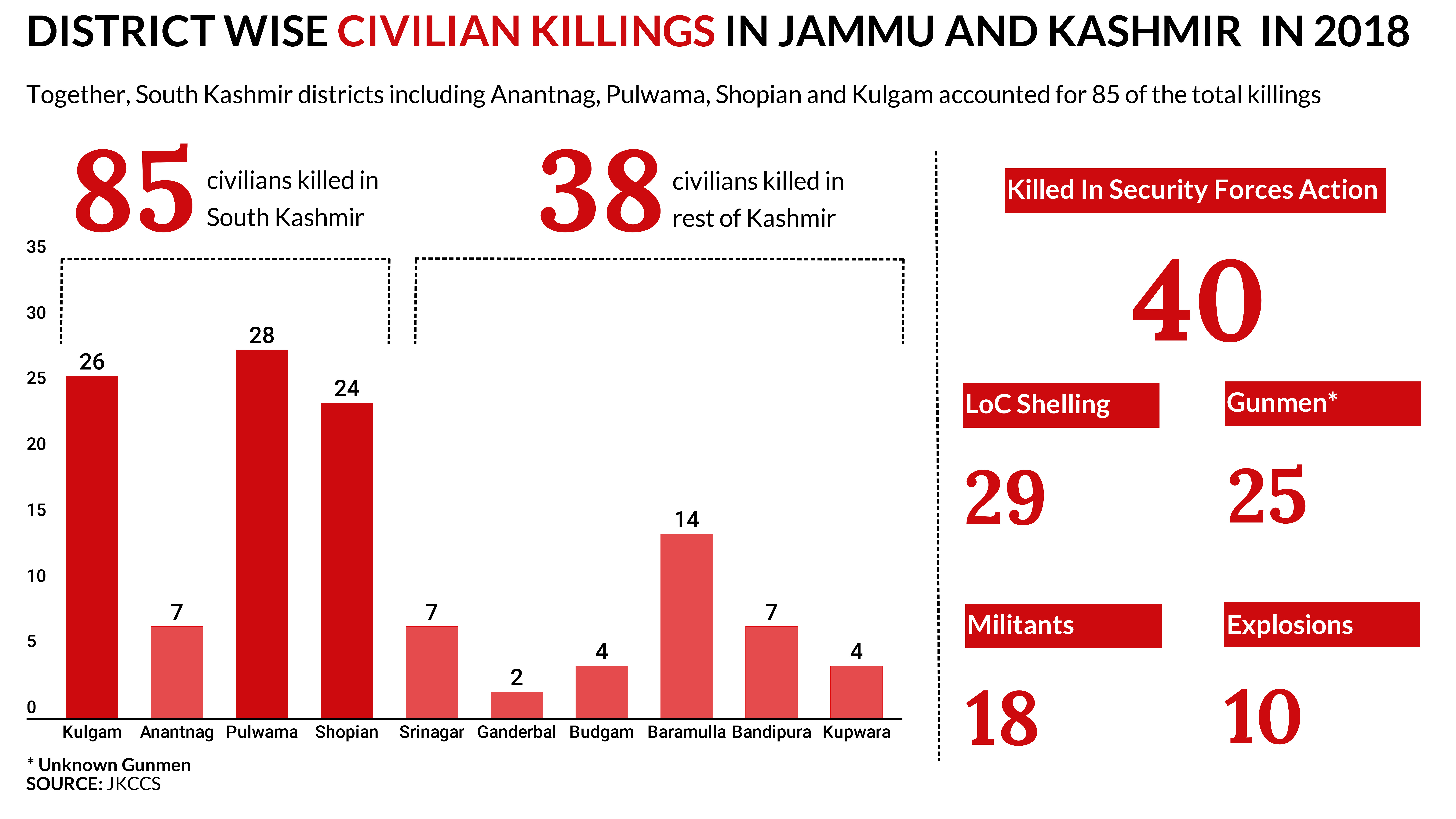

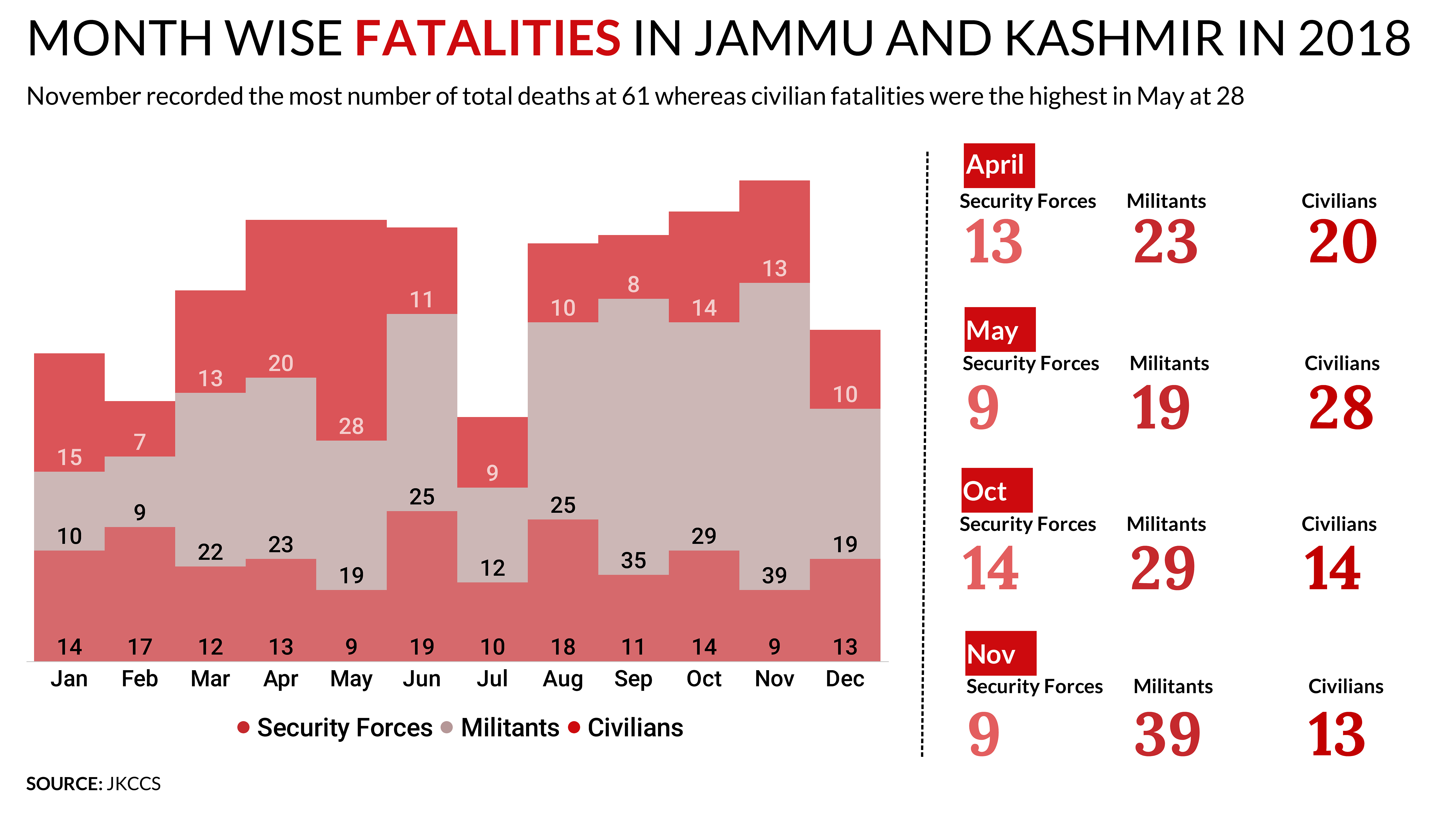

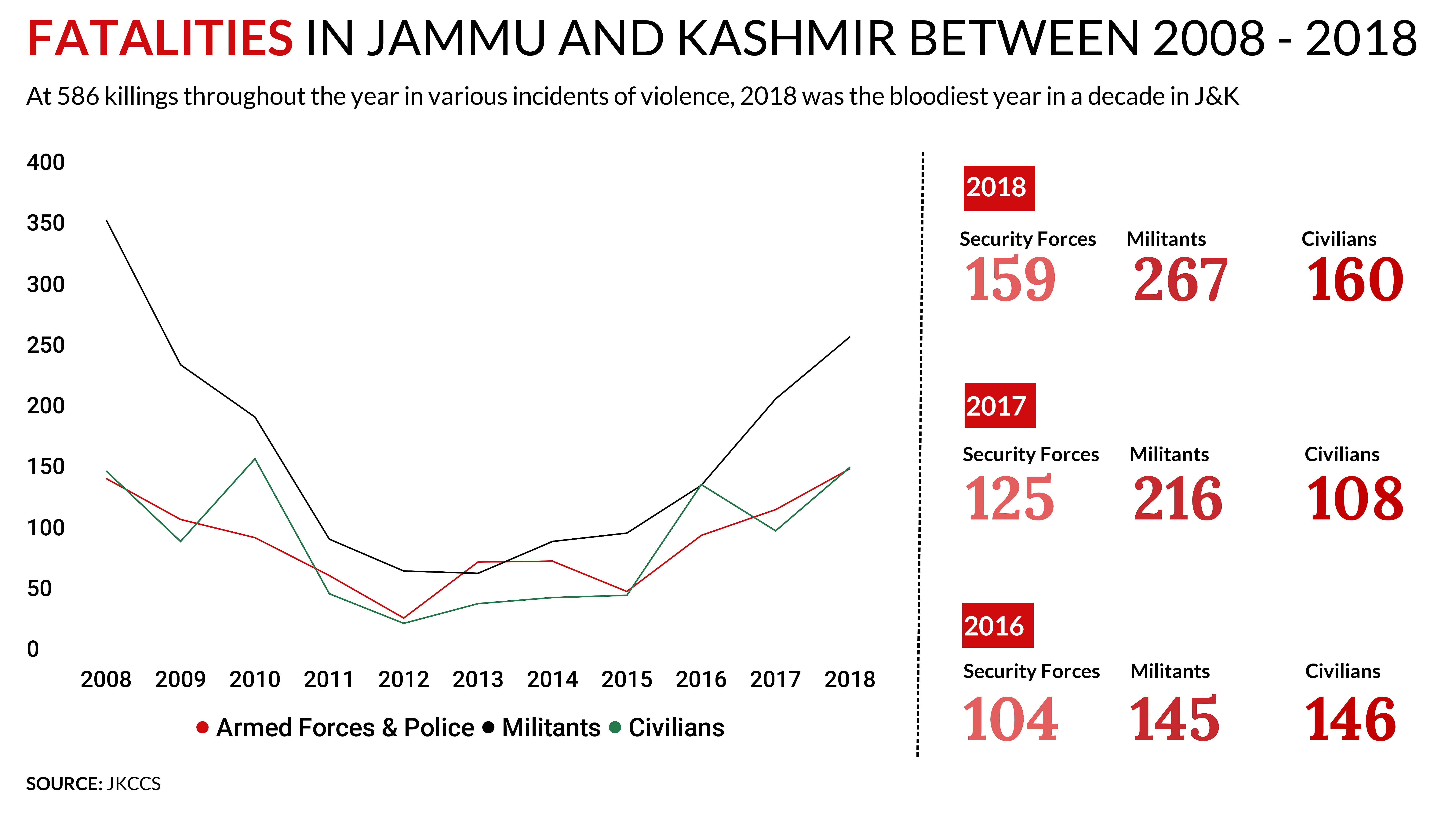

This trend of civilians trooping to encounter sites to shield militants may have intensified in 2018, a bloody year with 267 militant deaths in 143 encounters, but it actually started in 2011.

And it all began for just one militants who was holed in the house of one Abdul Aziz Khan in Puchul village of Pulwama. Security forces had cordoned off the house overnight and gunfight echoed at dawn. To their shock, civilians in nearby houses stormed out and started pelting stones at them.

Nine police personnel and six civilians were injured in clashes that sparked off the worrying trend of locals putting themselves in the thick of crossfire to save militants. The forces again faced the wrath of locals while returning after killing the militant, LeT commander Shakoor Ahmad Teli.

They were baffled. They had never seen this sort of anger among the people, never seen them storm into encounter sites like that.

“It was an extraordinary situation that time. We used to face resistance by people and stone-pelting incidents were common, but people would stay at home during encounters. They wouldn’t dare to venture out,” said a police official serving in Pulwama. He says that at the time, police had dismissed the popular resistant as a one-time event.

Shanawaz Ahmad, a college student then, was among the first batch of civilians ready to risk their lives. A private school teacher now, he feels 2010 was the year that changed everything for Kashmir. It was the year he weaponized a stone for the first time. He still remembers why. Protests had followed the ‘fake encounters;’ of three civilians. The army had branded them as Pakistani infiltrators, he says. The resulting violence led to over 100 hundreds. The youngest victim was 11.

“It was during this period that anger against the forces increased. We had seen the killing of young men. So, pelting stones was the only means to give vent to our anger,” he says.

What the army and police thought would be a one-time thing, has claimed 120 lives since 2017. While 78 civilians were killed near encounter sites in 2017, 46 were killed in 2018. In 2016, this act of rebellion took a dangerous turn, with such protests no longer confined to just south Kashmir.

THE BLIND RAGE

What drives a young man or woman to put themselves in harm’s way, knowing it may be the point of no return? Locals say it is the anger against security forces that simmers for long and then boils over. The source of that anger is more personal, some say. They talk of the high-handedness and disruptive ways of security forces during checks.

For some of these young boys, silence is sin. “You have to understand the situation through our eyes,” explains Huzaif, a 14-year-old student. “How can we continue normal life when there is a gunfight going on in the village. We know the people who are trapped there, fighting for us,” he says.

“These villages belong to us. When someone among us is being killed, how can we stay at home?”

Huzaif says it is not possible to isolate oneself from this endless cycle of violence.

His friend, Hashim, all of 15, says, “If I stay at home during these situations, there is this guilt inside me which throbs my soul… Yes, we may get killed in such situations, but there is no guaranty of being safe even if you are at home. So it is better to face it.”

Police, however, see it as a dangerous case of hero-worship. “Most of the militants get killed near their homes,” says a police official on condition of anonymity. “These militants are known among the local population. So, whenever there is a search operation, people think that a militant is trapped and they try to save him.”

In some cases, the civilians risking their lives don’t even know who they are doing it for.

A young man, who did not wish to be named, says, “It doesn’t matter which militant is trapped… When there is news of an encounter, I try to reach there as soon as possible. Most of the times, no one has any idea of who is trapped inside.”

The police official this reporter spoke to points to an elaborate network of over-the-ground workers, who spread word on which militant is trapped where. “Mostly, public address systems of mosques are used to make the announcements,” the official says.

THE COUNTER STRATEGY

Security forces are catching on. “Earlier, we used to avoid launching operations against militants in congested areas, mostly in the urban vicinities,” says another police official, working in Special Operations Group of J&K Police. “But now, we have been able to work in these circumstances as well.”

Army and police officials say that they are chalking out the strategies to minimise interference of people in encounters. But civilians believe, the forces are now using these clashes to set an example and send a message across.

Encounter site at Mujgund, Srinagar in which three militants were killed. (Photo: Aakash Hassan)

Civilian deaths have also led to several conspiracy theories. When seven people were killed in Kulgam after an explosion inside a house where militants were hiding, locals say the ‘bombs’ were planted by forces to create fear among local population.

CHASING PEACE

So is the ugly truth here to stay? Those ready to jump head-on into the violent abyss are just teens now. Is bloodshed their sole reality?

“Violence brews only violence,” says Arshad Hussain, a leading psychiatrist of Kashmir. “Whatever is happening is a reaction. If people are traumatised, do not expect flowers from them.”

Fearing for the future, Hussain is thinking about the much younger children who have been introduced to this chaotic world in person while their peers in the rest of the country witness it only on a screen.

“How they are going to grow and react? There has to be means and modes of dissipating the anger. When there is no way of expressing dissent, this sort of situation arises,” Hussain says.

Each clash, each death, each encounter triggers a political war of words. Representatives of parties come to blows in heated television debates. And lost in this noise are the silent screams of ordinary people, like Bashir Ahmad Bhat.

Grave of Zahoor Ahmad Thoker, an army man turned militant, who was killed in an encounter in December, 2018. (Photo: Aakash Hassan)

When he gets news of an encounter, Bhat is among the few civilians who rushes not to the encounter site, but to the hospital to help out. He did the same on December 15 after seven civilians were killed in Pulwama. While he was helping out as usual, a hospital employee was passing around the photo of one of the dead bodies, hoping someone would identify it. When the photo came to Bashir, he fainted. It was the photo of his 13-year-old son Aqib.

Author is a freelance journalist. Views are personal.

Comments

0 comment