views

A man scared of a bull is someone a woman should be loath to marry even in her second life.

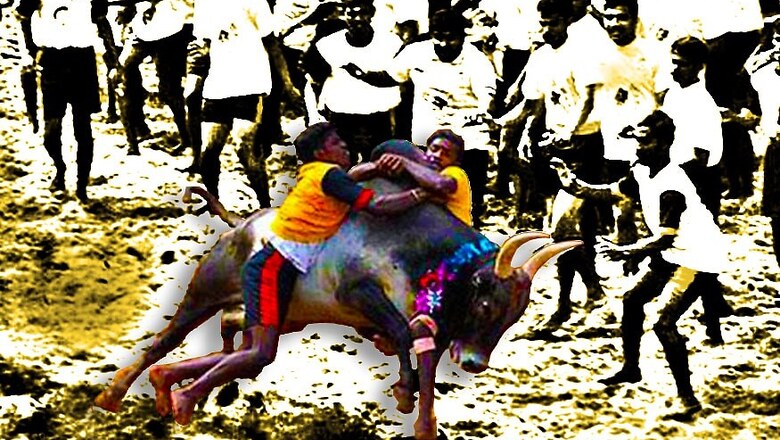

(From Kalithogai, a Tamil Sangham Era work)  There is adrenaline in the air. In a crowded maidan in a village somewhere near Madurai in central Tamil Nadu, hundreds of strapping young men look impatiently towards a small gate they call vaadi vaasal. Suddenly, the man at the microphone raises his pitch to feverish excitement, there is a deafening roar from the crowd as the gate opens and a bull with blood-shot eyes, a heaving ton of muscle and rage, charges out and ploughs into the mass of men. The most daring among them twitches through the flaying horns and threshing hooves and hangs on to its hump as the animal completes a short lap of 50 metres. In the wake, lie a clutch of men bloodied and writhing in agony.

There is adrenaline in the air. In a crowded maidan in a village somewhere near Madurai in central Tamil Nadu, hundreds of strapping young men look impatiently towards a small gate they call vaadi vaasal. Suddenly, the man at the microphone raises his pitch to feverish excitement, there is a deafening roar from the crowd as the gate opens and a bull with blood-shot eyes, a heaving ton of muscle and rage, charges out and ploughs into the mass of men. The most daring among them twitches through the flaying horns and threshing hooves and hangs on to its hump as the animal completes a short lap of 50 metres. In the wake, lie a clutch of men bloodied and writhing in agony.

For the Tamils, Jallikattu is veera vilayattu or warrior sport, where a man matches wit and sinew with a raging bull and grabs a small bag of coins or Jalli, tied to its horns. In the days gone, he would also win the daughter of the owner of the bull in marriage. It is about courage, masculinity, and above all, cultural ethos.Also Read: Pongal Festival Celebrated With Pomp, Gaiety in Puducherry

And, as it happens in many other parts of the world, cultural ethos conflicted with modern ethics and jurisprudence. The former bull-taming championship, which had mellowed into a sport through the centuries in a land where kingdoms rose and fell, was banned by the Supreme Court in 2014. The debate over the merit of that order continues to play out on television screens.

Jallikattu faced its first hurdle in 2004 when PETA (People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals) and AWBI (Animal Welfare Board of India) came together against it. On November 27, 2010, the Supreme Court allowed the sport to be played for a period of five months in a year under controlled conditions and in accordance with the Tamil Nadu Regulation of Jallikattu Act passed in 2009. Five years later it was completely banned.Through The Ages

Nobody knows when Jallikattu began. Scholars who argue on a Dravidian origin to the Indus Valley civilisation argue that one of the sealstones discovered from the site (2500 BC) actually depicts Eruthazhuval, a more traditional name for the sport. Numerous references have been found in Tamil Sangam literature (200 BC-200CE). In later days, Tamil kings used Eruthazhuval as a competition to recruit for their armies. And it is widely believed that the ancient southern kingdom of Pandyans, which had one of its headquarters in Madurai, took its name from Pandi, the Tamil word for a bull.Also Read: Jallikattu Supporters Continue Protests in Tamil Nadu, Many Detained

Animal rights activists see it otherwise. "The animals endure extreme bullying when they are chased by a mob of grown men who pounce on them, bite their tails, force-feed them alcohol, jab them with sticks and terrify them until they fall and even break their bones or sometimes die," says Sachin Bangera of PETA India.

Venkatachalapathy argues that stricter regulations, like the ones in force in, say, boxing, can control the gore to a large extent. “Boxing as a sport is regulated with rules like boxers having to wear gloves and protective headgear and a referee who can stop the match if a boxer is injured to a great extent,” he says. How far such regulations work in the outreaches of Tamil Nadu is debatable. Will Stricter Rules Work?

Experts point out that risk of injury to both man and animal sharply drops with experience. “Young bulls are brought to the arena where they don't get the nuances of Jallikattu, but the more experienced bulls know what to expect,” says Raja Marthandan, a member of The Biological Conservation of Bulls. He prescribes training as a way out.

A mature bull shows familiarity with the sport by shaking its head as a sign of warning before leaping forward with a well-timed jump that evades the swarm of tamers. Younger ones hesitate and do not time their jumps well leaving blood in the arena. The bull has to be tamed before it crosses the finish line, which is usually 50 metres from the entrance. Tamers are allowed to hold on to only the hump, and only one man can mount a bull at a given time. Flouting of rules will result in automatic disqualification of tamers.

Genetics and natural selection add another dimension to a debate which already has legal, political and sociological ramifications. A century ago, India was home to 130 native cattle breeds. Today, the number has dipped to 37. Tamil Nadu had six native cattle breeds, among which the Alambadi is no more. Kangeyam, Malai-maadu, Barugur, Umbalachery and Pulikulam are the remaining native ones.

The bulls are highly adapted to the environment. For instance, the Umbalachery can walk with ease in the water-logged fields of the Cauvery Delta or the Malai-maadu and Barugur can graze on hilly terrain. Healthy genetic traits of cattle breeds are passed on through generations, which is a reason for sending an untamed bull for breeding — the virility and agility is passed on to the calves.

"Is disrespecting a woman part of Tamil culture," she shoots back at the trolls.

Comments

0 comment