views

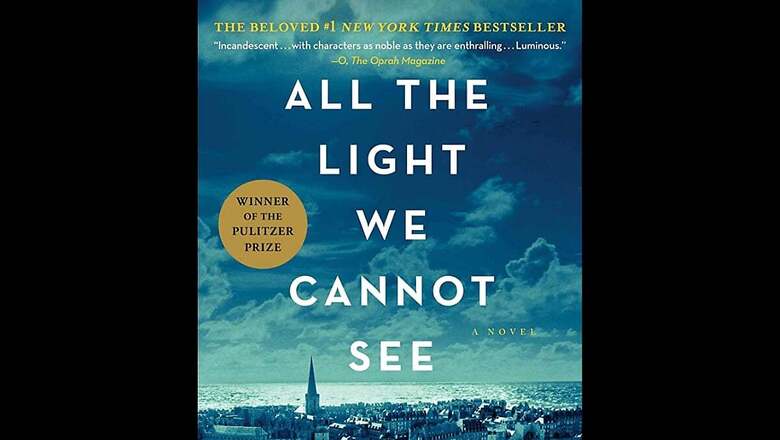

We often consider the world wars to be pinnacles of destruction. Lives were discretely ripped apart, whether they were part of the conflict or not. All the Light We Cannot See by Anthony Doerr illuminates to us the morality that man still holds within, that might flicker occasionally, but is still very much there, ingrained in our cores, our truest selves. The novel is a work of fiction rooted in Nazi Germany’s invasion of Paris.

It concentrates on two teenage characters leading parallel existences in juxtaposing environments. The protagonists are Marie-Laure, a blind French girl who seeks sanctuary at her uncle’s home in Saint-Malo after Paris is razed by the Nazis and her father is arrested, and Werner Pfenning, a brilliant German boy who is condemned to an unfruitful life in a coal mine when he joins a Nazi school.

Werner is initially intrigued by the grandeur of the Hitler Youth, sacrificing all he has to become a scientist, including leaving behind his younger sister, but is instead herded into military service. He is remarkably multifaceted — torn apart between his loyalty to country and the atrocities it has committed, as well as his own brilliance.

Marie-Laure is a character of complexity and resourcefulness, an adept heroine.

The story revolves around Werner and Marie-Laure’s many barriers in making something of themselves in a war where everybody is forgotten. Above all, it’s about how they, despite their dissimilarities, try to be good to one another.

The book recognises our own starvation for space. As Werner and Marie-Laure’s stories intersect, Doerr makes us realise how distressing the realities of war were, and through his laconic and ephemeral sentences, shows us how fleeting life can be.

The story keeps you on the edged, perpetually leaving you in a state of curiosity, and wonder, as you traverse the past century along with the protagonists.

The story is told through the perspectives of Werner and Marie-Laure, and switches regularly, giving you an opportunity to be fused with both characters.

The novel’s structure, with short, interwoven chapters, creates a compelling rhythm, but might seem slow-paced to some. Doerr manipulates a plethora of cacophonic sounds to annex the actuality of weaponry and genocide, which naturally contrasts with the delicacy of the internal strives of each character. His prose, however, is clean and lean despite the grime and tragedy of war that shadows it, but is nothing short of mesmerising, painting this world with remarkable precision.

I was constantly waiting for the story to turn a corner, to reveal slightly to us what might be the denouement, but Doerr weaves suspense so masterfully even in such a transparent environment that the reader is forever waiting. And eventually, the tumultuous ending after going through the brightest and darkest corners of humanity, leaves readers emotionally shattered with a glimmer of hope, the symphony of linguistic artistry and the profound truth of spirit.

This novel is a self-portrait of humanity, and while readers of ages above 10 might like this book, it is my recommendation that one should be a young adult or above in order to truly understand the magnetism it offers. The history might be of select fascination, and perhaps those with an interest will completely relish this story, but it is one we should all take in and learn from.

Aanya Thakur is a 14-year-old, Class 9 student of Dhirubhai Ambani International School. She is a voracious reader of varied genres and has a penchant for writing.

Comments

0 comment