views

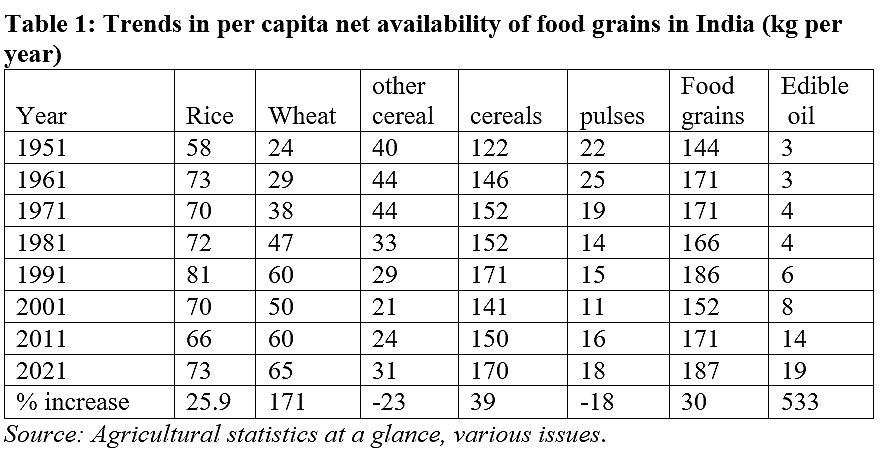

Indian agriculture, as the country is celebrating the glory of 75 years of Independence, stood strong with the remarkable achievement of surplus in foodgrain production despite the rapidly growing population from around 361 million in 1947 to almost 1.403 billion in 2021. The per capita availability of cereals increased by about 30 percent from 122 kg per person per annum to 170 kg, while that of edible oils recorded a manifold from 3 kg to 19 kg during the past seventy years.

Nevertheless, India remains a net importer of both pulses and edible oils to meet the domestic consumption demand. More importantly, the per capita availability of pulses declined to 18kg per annum in 2021 from 22kg in 1951, indicating the urgent need for raising their production. Under such a scenario, diversification from cereals to pulses and oilseeds becomes a priority not only for achieving self-sufficiency towards nutritional security but also for ensuring sustainable agriculture through regeneration of soil fertility and conserving ground water resources.

The emphasis on crop diversification brought about in the latest governing council meeting of Niti Aayog was long pending and requires an immediate action plan for implementation. While the need for diversification has been pronounced widely in the past two decades or so, its implementation has not been ensured with adequate policy thrust. But with growing focus on climate smart agriculture and reducing emissions towards achieving net-zero, it is now essential for ensuring the shift towards crop diversification from highly intensive mono-crop cultivation.

The trends in per capita availability of foodgrains during the past 75 years or so suggest that except for pulses, net availability of all other food items increased (Table 1). Area under pulses has increased at an annual growth rate of 2.23 percent per annum in the 1950s to reach over 24.2 million hectares in 1960-61 but has declined thereafter to about 21.8 million hectares in 1972-73. Although it has improved to 23 million hectares in the 1980s, it remained more or less stagnant at around 23 million hectares, barring a few spikes in the late 2000s.

There were three important reasons for the slow growth pattern in the production of pulses. First, substitution of pulses by other crops; second, shift in pulses cultivation to less productive dry lands; and, third, limited improvement in the yields of pulses compared to other food crops.

Among all the pulses, substitution was more prominent in case of chana as indicated by the fall in area at an average rate of -1.46 percent and -1.34 percent per annum respectively during the 1960s and the 1970s. Research indicated that the increase in area under wheat in rabi after 1965-66 in states like Punjab, Haryana, Rajasthan and UP was claimed mainly by acquiring area that was under chana in the earlier years. This has led to persistent shortage in pulses and thereby resulting in import dependency to fulfil nutritional security and meet the domestic consumption needs.

Traditional Indian agricultural practices and cropping patterns were more congenial for the environment facilitating soil regeneration and water conservation by appropriate crop mixes, but constrained by the low-yielding crop varieties. In order to achieve self-sufficiency in foodgrains, green revolution technology was introduced in the mid-1960s with input responsive high yielding varieties (HYV) coupled with input (water, fertilisers and pesticides) intensive practices and price support policies. However, the success of green revolution technology was largely confined to wheat and rice in terms of HYVs and price support policies with assured procurement. This has led to extensive cultivation of wheat and rice (cereal-cereal) cropping patterns shifting from different combinations cereal-pulse or cereal-oilseed cropping patterns with suitable crops.

Thus, although there is remarkable progress in terms of food availability with increased production of all major food crops, there is an urgent need to focus on crop diversification for promotion of cultivation, marketing and demand generation of nutrition-rich foods like coarse cereals and pulses. Some of the states have initiated various measures to promote crop diversification. The Madhya Pradesh government recently launched a crop diversification promotion scheme focusing on substituting wheat and paddy crops with other crops like soyabean, which are suitable for local climate and facilitate natural farming through regeneration of soil fertility.

Dr A Amarender Reddy is Principal Scientist (Agricultural Economics), ICAR-Centre Research Institute for Dryland Agriculture, Hyderabad. Dr Tulsi Lingareddy is an economist — financial markets, sustainable finance and climate change. Views expressed are personal.

Read all the Latest Opinion News and Breaking News here

Comments

0 comment