views

It is with a heavy heart and a mixed bag of emotions we contemplate and deliberate upon the successful completion of two POCSO trials within a month’s time in Surat. Mixed because, first, the heinous and monstrous crimes against minors must not happen, and second, the lackadaisical pace and apathy of the judicial system that unnerves and dissuades the victim or her family from appealing for justice.

These two judgments by the POCSO (Protection of Children from Sexual Offences) court in Surat ought to be a reflection of larger problems, ironically. In the diamond city, which invariably ranks as one of the safest in the country, and rightly so, there were two reported rape incidents involving minors. A four-year-old and a two-and-a-half-year-old girl were raped, and the latter was murdered. This will boil any citizen’s blood, and the least one would expect is justice. Usually, due to various reasons, such cases hang fire for years. But justice delayed is justice denied.

As per data, “From January to June 2019, 24,212 cases of child sexual assault or abuse were registered under POCSO, of which 27 per cent of cases went on trial, as was noted during the parliamentary debate during the amendment of the Act; 4 per cent of cases were completed.” The Supreme Court issued directions to districts with more than 100 pending cases under the POCSO Act to set up fast-track courts with a resolution deadline of 60 days. As many as 1,023 fast-track special courts for POCSO cases would be set up, said Smriti Irani, Minister of Women and Child Development, who introduced the POCSO (Amendment) Bill in the Rajya Sabha.

According to 2018-19 Economic Survey, with 28.7 million cases pending in district and subordinate courts, there are currently 17,891 judges against the required strength of 22,750. Over 4 million cases are pending in the country’s high courts. Further, high courts have 62 per cent of sanctioned judges, with only 671 out of 1,079 judge positions filled.

But this wasn’t the case this time, in Surat. On October 11, 2021, Ajay, alias Hanuman Nishad Kevat, 39, found a 4-year-old girl playing with her friends in Sachin GIDC, Surat. He lured her into the bushes, where he raped her and left her in pain. In an exemplary move, the local police caught the accused the next day, and a chargesheet was submitted within 10 days. The trial was completed within six days in the special court, and the accused was convicted under the POCSO Act. The court sentenced him to life imprisonment and ordered him to pay a fine of Rs 1 lakh.

In the second incident, Guddu Yadav, a migrant worker, raped and murdered a two-and-a-half-year old girl on November 4. The police formed a task force of 100 personnel and filed a 246-page chargesheet within seven days, and acted as promptly as they could to initiate the trials. The special POCSO court sentenced the guilty to capital punishment under Sections 302 and 376-A and 376-B of the IPC and POCSO Act in a record time of 21 days. Nayan Sukhadwala, the public prosecutor, urged the court to consider the crime as “rarest of rare” and cited 31 judgments pronounced by different courts in similar cases in the past to demand capital punishment. The special court also directed the state government to pay a sum of Rs 20 lakh to the family as compensation.

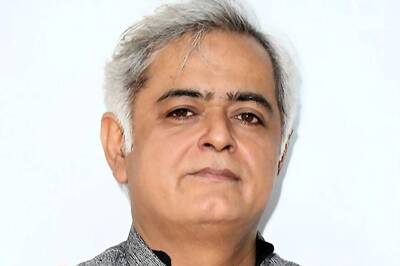

When Sukhadwala was contacted—we owe him a big congratulatory note since he was the public prosecutor in both the cases and played a key role in expediting justice—he was modest enough to share the credit with his entire team and lauded the promptness shown by the local administration. When asked how he managed to bring the guilty to book in record time, he said the local police and medical authorities extended full cooperation. In most cases, the logistical problems lead to delay in hearings, like the transfer of an investigation officer or the unavailability of witnesses.

In these two cases, such problems were avoided due to the promptness of the local administration. As a result, the trials were completed within the 60-day time limit laid down by the Supreme Court. The POCSO Act was amended in 2019 and the clause on capital punishment was added. While congratulating the government on the move, he said, “I am very satisfied with the trials, and no amount of fees would have given me the same happiness.” He also said that technology could prove to be a great tool in expediting the judicial process, especially when logistical problems hamper it. “He provided a great example to the legal fraternity throughout the country and shared valuable insights that would inspire many young lawyers and law students in the future,” said Darshan Vankawala, an eminent lawyer and activist based out of Surat.

One finds that there’s more to these two cases than meets the eye: they provide a ray of hope for overhauling the entire judicial system and its processes in the country. The Surat model has been quite motivating, and the proactiveness of the local administration, along with the other factors, could be emulated in other parts of the country. This only furthers the argument that with smooth and streamlined coordination at district level, a robust justice delivery mechanism is possible. And Surat has shown the way, leading from the front.

Yuvraj Pokharna is a Surat-based educator, columnist and social activist. The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not represent the stand of this publication.

Read all the Latest Opinions here

Comments

0 comment