views

As capitalism and commercialisation slowly pervade every sphere of our daily lives, the struggle to maintain our traditional roots gets all the more complicated. What were once places and systems of worship and rituals, are now places of trade, profit and consumerism. With this in mind, let us turn our attention to Sumo Wrestling Arenas, or “Kokugikan”, which are the very embodiment of the intersection between tradition and consumerism.

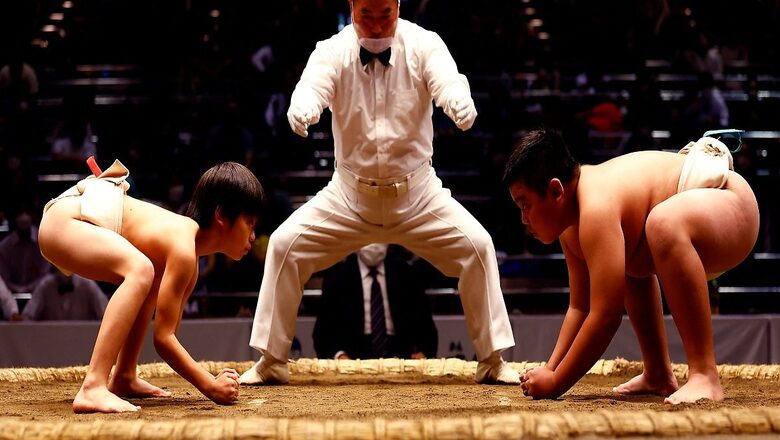

Sumo Wrestling is Japan’s oldest sport which is said to have originated from a wrestling match between the Shinto deities Takemikazuchi (God of Thunder) and Takeminakata (God of Water), and hence carried an association with praying for a good harvest. Evolving through history, it came to be court entertainment for Emperors, martial art rituals for the Samurai castes, and finally an organised and professional sport, that exudes Japanese culture in the rawest sense.

Sumo wrestling, although a sport, still retains its religious and ritualistic nature. However, while it maintains its sacred associations with the Shinto religion, it has not been able to escape the effects of capitalism like almost any other sport. The Kokugikan buildings are the physical manifestations where the Shinto deities and capitalist strongholds converge and coexist to maintain each other.

Sumo is starkly distinct from other sports, in that the rituals are an inherent part of the support itself, and the rituals become a part of the ‘spectacle’ that is meant to be seen and marketed as the soul of ‘Japan-ness’. Sumo bouts last from about a few seconds to a few minutes. If so, then why would each day of the tournament start at 8:30 am and end at 6 pm? One reason is that because the rituals are an integral part of the tournaments, they usually take longer than the bout sessions themselves. Removing them would mean diluting the overall experience of Sumo for the audience and the inherent affective bond that the Japanese feel for their religion and national sport.

An interesting point to note is that, while there has not been a direct dilution of the Sumo experience with regards to the rituals, the media plays a significant role in the marketing of Sumo, and the time taken for the rituals and the interval between the rituals and bouts have been shortened, in order to align with the time slots available for broadcasting. NHK World (the international parallel for Japan’s largest broadcasting company), broadcasts a “highlights” version that condenses 2 hours of the top division bouts into a 25-minute slot for the overseas audience. Furthermore, earlier the bouts could begin as soon or as late as the opponent rikishi (Sumo wrestlers) were ready. However, with the time crunch that comes with the commercialisation of a sport, the time for the stand-by build-up before the initial charge (tachiai) between the rikishi has been reduced to a maximum of 4 minutes. Also, to facilitate a smooth viewing of the bouts, it was suggested that the pillars of the roof over the “Dohyou” ( space within which the wrestling bout occurs), be removed. Since the pillars were removed, the roof structure was adjusted to be suspended from the roof. The interesting addition here is that with the advancement in technology, video cameras are now fitted inside the roof structure. This cleverly blends traditional designing with technological change that provides a heightened experience of Sumo to its fans.

When a ritual-oriented sport evolves to include commercialisation, there is a change in the way we demonstrate the cultural specificities and nuances to a larger and more globalised audience. For instance, before the Sumo bouts begin, there is a short demonstration of the “Kinjite” (forbidden techniques of foul moves). Currently, there is a humorous twist added to the Kinjite demonstration. This is perhaps one way to keep the audience engaged, since engaging with the audience is ultimately what brings in the profit. Also, with a dash of humour, the surging influx of foreign audiences understands the local context and rules of the sport much better.

Another example of attempting to connect with a wider global audience can be seen at the procedural level. The official Sumo website has its own English version available that caters to the overseas audience, with English as the common string connecting foreigners to Japan. Moreover, the pamphlets and guide booklets also have English versions as well. While a multilingual guide can be found at almost any major tourist attraction in any country, Sumo stands out because it is a combination of a ritual, a sport and a striking touristic endeavour.

With the evolution of technology, media and society itself, there has been a significant shift in the way we come to see the bodies of the “Rikishi”. The robust bodies of the Rikishi, which were earlier a sign of a resourceful family and lineage in terms of having enough to eat, are now seen as unhealthy. Our changing ideas and culturally different acceptance of what constitutes a ‘healthy’ body put a certain pressure on the Rikishi to conform to the ‘muscular is strong’ narrative. While it is true that Rikishi have a lot of fat on their bodies, the value attached to that fat is different. For the Rikishi, it is a tool that gives them leverage over their opponents, especially when it comes to the belt fighting style (known as Yotsu-Zumo). Sadly, what is often overlooked, is the tremendous amount of effort the Rikishi pour into their training every single day. The Rikishi are far more muscular, flexible and fit than the average person, but alas, overt appearances veil the blood, sweat and tears that are merely confined to the Sumo training stables.

From another perspective, fat is seen as an ‘unfortunate’ substance, in the sense that only those who were ‘unfortunately’ fat, had to go into the field of Sumo. From yet another perspective, the fat becomes a commodity used to generate eyeballs and take in larger profits.

A sportsman’s Identity comes from not only one’s ability but also the unique style in which the individual imbues the sports field with the aura that is part of him or her. In Sumo, the Rikishi express a part of their ‘being’ into the sport, via their Shikona (ring names), Mawashi (the belt) and unique style of carrying out the Shiomaki (salt-throwing ritual).

Ring names take on an adhesive nature of sorts, unifying the self-concept of the Rikishi as people and also the self-concept of the Rikishi as sportsmen. The ring names or part of them often include animal names that metaphorically symbolise the Rikishis’ skills. For instance, the name Tobizaru literally translates to ‘flying monkey’, which reflects his monkey-like agility, and appears to be flying due to his nimbleness during bouts.

Clothes are a social tool that helps us communicate who we are to the world. Similarly, the scantily clad Rikishi wear their identity not on their sleeves, but on their Mawashi or loincloth belts. The top division is permitted to wear silk Mawashi in colours of their choice, while the lower ranks wear dark-coloured Mawashi made of cotton. While the colours are often just a matter of personal preference in terms of what the Rikishi like, the element of ‘lucky colours’ cannot be dismissed as simply superstitions, because humans will always retain at least some amount of superstition, regardless of the scientific and technological advancements they make.

A very important thing to be mentioned is the Kesho Mawashi with heavy embroidery, only worn during the ring entrance ceremony by top-ranked Rikishi. The Mesho Mawashi are a prime example of how identity, commercialisation and globalisation come to reside in one single piece of cloth. Many Rikishi have their favourite manga or anime characters embroidered on their Kesho Mawashi, or perhaps animal designs that align with their Shikona. While the Kesho Mawashi embroidery design is something that also reflects who the Rikishi is as a person, sometimes they are gifted to the Rikishi by local or overseas fans. The increasing number of foreign Rikishi, as contrasted with the continually dwindling native Rikishi, becomes grounds for increased foreign involvement as well as increased investment in Sumo in terms of resources like money and support.

Furthermore, a distinct observation of marketing sponsorship can be seen before certain bouts begin. A Rikishi’s personal popularity brings more wealth to the Sumo Association as an institution. This in turn leads to more sponsors who are willing to invest in the maintenance of promising sumo wrestlers. And this increase in sponsorship can be seen when the Yobidashi (ring attendants) walk around with flags bearing the logos of the sponsors. This is perhaps the strongest form of commercialisation that can be observed in this two-way alliance formed between those who play Sumo and those that Sumo is played for.

While all Rikishi earn quite a hefty sum of money as sportsmen, the winners of bouts can be seen getting envelopes, (or even massive stacks of them) from the Gyouji (referee). These envelopes containing prize money are again from sponsors that reward the Rikishi for their performance. From a psychological viewpoint, it is an extremely cleverly crafted positive reinforcement system that not only boosts the morale of the Rikishi, but also the bank balances of various parties involved.

Lastly, the Shiomaki, or salt-throwing ritual, is one of the most salient features of Sumo. Salt is believed to drive away evil spirits, and before entering the ring, each Rikishi tosses large handfuls of salts in the air. This too, has a dual purpose — one, to perform the Shiomaki ritual of course, and two, as a drying substance that wipes off the sweat from the palms of the Rikishi. The aspect of identity also percolates down into the Shiomaki, wherein the unique manner in which a Rikishi tosses his salt, becomes yet another part of who he is.

Hierarchi-sation is a significant social factor that has an overarching effect that governs the way we interact with others. Japanese society by nature emphasises politeness and respect as the most important virtues, but it is hard to do away with the hierarchy that prevails. The Japanese are socialised in such a way, and Sumo is no exception to this norm. This hierarchisation has been monetised too, in that the ranks take on a value beyond that of respect. Of course, those who occupy the higher ranks in the Sumo hierarchy are there by virtue of their hard-earned wins. Apart from the Rikishi, even the Gyouji are organised into ranks. The rank system of the Gyouji is based purely on seniority, which differs majorly from that of the Rikishi which is based on performance. These ranks, as mentioned earlier in the case of Rikishi, are apparent in the Mawashi fabric and colours. Similarly, for Gyouji, being barefooted, wearing socks and wearing socks as well as sandals, are dressing indicators of their rank.

The societies we live in are all more or less characterised by hierarchies and classifications — that are either achieved or ascribed to us. While this is true of any society, Sumo parallels this larger societal system into its niche sporting system, and offers us an opportunity to experience a ‘mini-society’ in itself. Sumo brings together the multifarious strings of religion, sport, capitalism, globalisation, inscriptions of meaning onto the bodies of certain people, and social relations, in one compact space — the Kokugikan.

Yashee Jha, a multi-faceted student, is an avid commentator on various topical issues. Views expressed in the above piece are personal and solely that of the author. They do not necessarily reflect News18’s views.

Comments

0 comment