views

Paris: The trader blamed for the world's biggest banking fraud was a junior banker who used his intimate knowledge of Societe Generale's risk control systems to conceal months of illegal dealing, the bank and insiders said on Thursday.

Sources within SocGen named the dealer as 31-year-old Jerome Kerviel, who worked on the bank's European equities derivatives desk at its Paris headquarters and earned less than 100,000 euros ($146,500) a year.

SocGen accused the trader of taking "massive fraudulent" positions in 2007 and 2008 on European equity market indices, leaving them nursing 4.9 billion euros of losses as they unwound the positions in wildly turbulent markets this week.

A senior bank board member told Reuters that Kerviel "was not a star," but Bank of France Governor Christian Noyer told reporters that the rogue trader was a "genius of fraud."

Kerviel was last seen at SocGen on Sunday prompting speculation he since may have fled or be hiding, but a woman identified as his lawyer by French television said he was ready to speak with authorities.

"He is not running away. He is at the disposal of the police," lawyer Elisabeth Meyer told BFM-TV late on Thursday.

Meyer, a well-known Parisian lawyer, was not immediately reachable.

The problem came to light at the end of last week, and Kerviel met bank executives face-to-face at the weekend as they tried to unravel the web of deceit that cut through all the company's supposedly sophisticated safety mechanisms.

"It turns out that this was possible because it happened to be someone who had knowledge of the internal control systems from his earlier career and who is no doubt a computer genius," Noyer told a press conference.

Kerviel joined SocGen in 2002 and was trading in one of the most basic financial instruments in the complex world of derivatives -- futures contracts on European equity indices.

It appears that he bet massively and mistakenly on a rise of European equity indices.

Next: How it snowballed

PAGE_BREAK

HOW IT SNOWBALLED

One banking insider estimated that the loss was worth "just" one billion euros at the weekend, but it rapidly snowballed when SocGen moved to purge their books on Monday and Tuesday as European stock markets plunged.

"These losses could have been gains if the market had climbed on Monday, Tuesday and Wednesday," Societe Generale Chairman Daniel Bouton told a news conference.

As a junior staffer, there were strict limits on the positions he could take, but he knew how to bypass these controls because of five years spent at the back and middle office of the bank at the start of his career.

"He managed to conceal these positions through a scheme of elaborate fictitious transactions," SocGen said in a statement. But colleagues were mystified by his motivation.

Officials said there was no indication he was trying to steal money from the company, or was working with anyone else.

"His motivations are totally incomprehensible. It does not seem that he would have profited directly from this gigantic fraud," Bouton said.

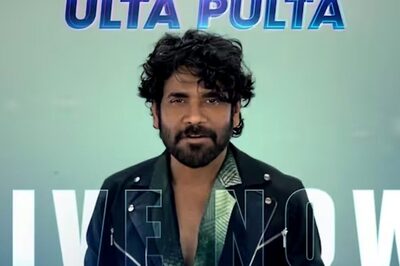

A headshot of him cut from a trading Web site showed an earnest-looking young man, glaring at the camera with a hard frown and pursed lips.

He had an account on the facebook.com social Web site. At the start of the afternoon, when his identity was revealed, he had 11 friends listed. That number dropped to 4 just hours later.

A NEW LEESON?

The hole in SocGen's accounts dwarfed the $1.4 billion loss by trader Nick Leeson, which brought down British bank Barings in the 1990s, but comparisons between the two cases are notable.

In both cases, the traders had worked in the back office, learnt all about the computing systems and were then promoted to the trading floor where they built up huge losses under the noses of their unsuspecting bosses.

Next: A lesson to be learnt

PAGE_BREAK

One security expert said it was unusual that someone with up-to-date knowledge of risk control systems should have then gone straight into a job involved in trading.

"Knowledge of anything is a powerful thing in the wrong hands and if you know what the security controls are it makes circumventing them easier," said a London-based consultant in security systems with a professional services company.

Yet many bankers were astonished that his bosses failed to detect the fraud earlier.

"Everyone is asking themselves ... how just one trader, all alone in the corner, could have beaten all those whiz kids who throng around in Societe Generale," said the head of derivatives trading at an American bank, who declined to be named.

"Five billion euros of losses is enormous. It represents a position of several dozens of billions of euros, perhaps 30 or 40 billion. How can one person all by themselves do that?"

Police, SocGen and the Bank of France have all launched investigations to try to find the answer.

Comments

0 comment