views

Completing Your Initial Education

Develop your reading and writing skills in high school. Select additional history or English courses as your electives. Take as many advanced placement (AP) courses as you can. These will help to prepare you for college-level essay writing. Join clubs that emphasize critical thinking and the use of evidence, such as Mock Trial.

Get your college degree in history or a related subject. It’s best if you major in history at the undergraduate level, but a degree in English, Legal Studies, or another humanities or social sciences field can be useful as well. You’ll need a B.A., at minimum, to go after a career as a professional historian. Getting into a great university and achieving high grades will make transitioning to graduate school or real-world employment easier, too. Seize any opportunities to distinguish yourself as a history scholar, such as writing an honor’s thesis. If you choose a major outside of history, make sure to fit a number of history classes into your schedule regardless. It’s especially important to enroll in classes where you’ll be given the opportunity to conduct research with materials from other time periods. Plan your classes in a way that ensures that you’ll work with the same professors multiple times prior to your senior year. This makes it easier for them to write you convincing letters of reference.

Focus on an area of historical interest. At the undergraduate level, start to pay attention to the time periods, places, or themes of history that excite you. It might help to ask yourself which historical questions peak your curiosity. Don’t worry about narrowing everything down too much in college, you’ll have plenty of time to do this if you pursue a graduate degree. For example, you may want to focus on the tiny details of people’s lives. Or, perhaps you’ll want to study life in a certain decade, like the 1950s.

Apply to graduate school. Decide if you want to attend a master’s only or doctoral (PhD granting) program. Research possible schools by talking with your undergraduate professors and reaching out to active historians and potential mentors via email. Prepare and send off your application package with all of the required materials, including your GRE scores, the application fee, a letter of introduction, a writing sample, and any letters of reference.

Focus on your grades in school. It will help to strengthen your application. Take the time to personalize your application essay. Get a recommendation letter from a teacher with whom you have good relations.

Get recommendation letters from the teachers who know you the best. You can also narrow down your school choices by looking into the educational backgrounds of your favorite historians. It’s possible that one of your undergraduate professors might offer to contact another professor for you to inquire about a graduate program. If they offer to do this, be appreciative and accept their help. You’ll receive acceptance and financial offer letters from graduate schools in the mid-spring. Make sure to carefully read over any fine print involving fellowships or assistantships.

Getting Your Graduate Degree

Excel at graduate coursework. You’ll usually take both colloquiums (reading and analysis classes) and seminars (research and writing classes) for the first 2-3 years of any program. Make sure to focus all of your attention on getting high grades in these courses. An “A” or “A-“ is a strong grade, but a “B” can mean you may need to put in more effort. Try to take courses both in your specific areas of historical interest and outside of them as well. This will give you a good foundation of information to use for teaching or research.

Pass your comprehensive exams. You will take qualifying, also called comprehensive or “comps,” exams after you finish your coursework. These exams usually have two parts: a series of written essays and an oral examination. They are designed to cover the information that you’ve learned so far in your history graduate coursework. After you’ve passed, you enter a stage known as “ABD” or “All But Dissertation.”

Write a thesis and/or dissertation. If you are in a master’s program, you’ll need to complete a thesis project using original materials. If you are in a PhD program, your dissertation will a book-length work that demonstrates your mastery of your subject matter and your ability to work with sources. It may take three years or more to complete. As you move through graduate school, you’ll have at least one faculty mentor or advisor who will supervise your research progress and offer professional advice. A master’s thesis is shorter than a dissertation. For example, a thesis might be 150 pages and a dissertation might be 250+ pages. As part of your thesis and dissertation research, you’ll usually need to visit archives and libraries. After you gather your research, then you’ll begin the writing process.

Pass your defense and graduate. When your dissertation is complete, you’ll submit it to your graduate program for approval. They will then schedule your defense. This is where you’ll talk about your work and defend it in front of a faculty committee. After you’ve passed your defense, then you are ready to graduate. Congratulations!

Doing Historical Work

Find a job as a professional historian. Degreed historians can find jobs in a variety of settings. Some Ph.D.s prefer to work as university professors, while others take positions with the government or branch out as independent consultants. Be aware that research-heavy jobs usually look for historians with Ph.D.s.

Be open to other career options. With or without a degree, historians can also work in museums, non-profits, and even in high school education. Make sure to keep your mind open when exploring your career choices. Focus on your skill set of critical thinking, writing, and reading. Look for jobs that emphasize those skills.

Seek out opportunities to publish. You can publish throughout your entire lifetime, with or without a degree. For the amateur historian, local historical magazines are always looking for interesting contributions. As a professional historian, aim for peer-reviewed journals and university-press published books. Publishing is one clear way to distinguish yourself in the field. If you decide to work as a professor at a research university, expect a rigorous publication requirement amounting to one journal article every two years and a book every five or so. Be patient when trying to publish. You’ll likely get rejections, as well as opportunities to revise and resubmit.

Attend conferences. Historians love to gather together in conferences and meetings around the world. Many of these gatherings are organized around a particular historical interest or theme, such as medical history. These are great opportunities to mingle with like-minded people and to learn more about history in general. If you have original historical research, go ahead and submit a proposal to present at a conference. You might want to start with a small, local group and work your way up to a national or international setting. Most conferences send out a Call for Papers (CFP) well in advance of the meeting date. The CFP will tell you how to submit your paper for consideration.

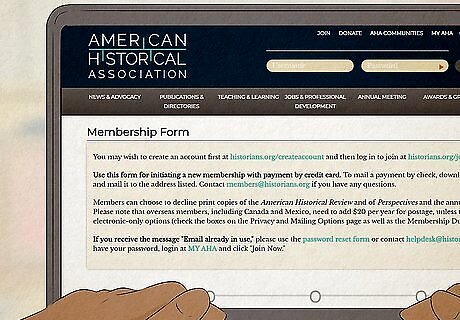

Join a professional history organization (PHA). There are a number of groups out there that cater to particular historical subsets. Look for an organization that fits your interests and that would give you a chance for active membership. Being a member often grants you perks, such as private events at museums or archives. For example, the American Historical Association (AHA) is the go-to organization for most historians practicing in, or studying, the Americas. Be aware that many of these organizations require hefty membership fees. However, ask about educator, senior, or other discounts.

Complete oral histories. Reach out to your family members and older friends to see if they’d be interested in sitting down with you and recording their memories. Then, you can make copies of these tapes or transcripts and offer them to archives and libraries. This is a great way to contribute to the historical record. Try to keep your oral interview questions open-ended. You want to give your interviewee plenty of time to talk. For example, you might ask, “Do you remember how you felt at that moment?”

Conduct genealogy. Historians are often interested in family connections and genealogy gives you the chance to trace these relationships. Talk with your older family members to see what they remember about their relatives. You can also go online and use a resource, such as Ancestry.com, to examine personal records.

Comments

0 comment