views

Understanding hoarding

Learn about hoarding disorder. This can help you to better understand your parents' (and your own taught) behaviour. Hoarding is characterised by an intense difficulty throwing things away along with a tendency to bring new items in. It is unknown exactly what causes hoarding; however, these are the risk factors: Personality. Most people who struggle with hoarding have indecisive personalities and have trouble making decisions. Family history. A strong association exists between having a family member who hoards and being a hoarder yourself. Stressful life events. Individuals often develop hoarding disorder following a stressful life event they struggle to manage, such as the loss of a loved one, a divorce, or losing belongings in a fire. Intergenerational traumatic experiences with war or famine. Hoarding can originally stem from the complex socio-economic issues of war and famine, as holding onto possessions becomes necessary to live under those conditions. This is the most common root of hoarding if you trace it back to grandparents and great-grandparents. Mental illnesses. There are many mental illnesses, or neurodiversities, associated with hoarding. These include: OCD OCPD ADHD Depression Generalised anxiety Psychotic disorders, such as schizophrenia

Recognise the difference between normal clutter and compulsive hoarding. Normal clutter will not impact your ability to live your life. This includes basic daily tasks, such as making food, cleaning yourself, using the bathroom, and doing the laundry. Compulsive hoarding leads to a far more chaotic environment that may be unsafe to live in.

Recognising the emotional and mental challenges

Acknowledge feelings like frustration, sadness, or anger. All of these feelings are a valid response to your living situation. You may feel angry at your parents for bringing you up this way or frustrated with the chaos. Feeling sadness or grief over lost opportunities, such as the ability to invite friends over, is also normal. Along with this is often the intense embarrassment and shame that comes with growing up in this situation. Identifying these emotions without dismissing or judging them is the first step toward understanding your emotional reactions.

Understand how the chaos may impact your self-esteem and mental health. Growing up in a hoarded environment poses many risks to your mental health and well-being. Embarrassment about the house’s condition causes increased stress. Arguments between children and parents are increased due to the mess. Also, just between parents, as they may argue about the cause of the mess or who is going to fix it. Isolation caused by being unable to invite friends over. Guilt from the excessive guilt-tripping that your parents may have developed. You might feel as if it is your fault that the house is in the state it's in, despite you being the child in the situation. Depression and anxiety brought on by the inability to perform basic daily tasks and being overwhelmed by the house's situation being placed upon you to fix.

Notice unhealthy coping mechanisms you may have developed. Due to the severity of your home environment, you have likely developed some coping mechanisms to deal with the stress and chaos. These may include coping mechanisms like: Substance abuse. This can be to cope with such an environment emotionally with downers. If you find yourself drawn to uppers, it may be in an attempt to clean it yourself. Please seek support for this, although you have to choose to recover. Seek support from an addiction hotline. Try to overcome your addiction. Self-harm. To deal with the stress of such an environment, some may fall into self-harming behaviours. Call an emergency number if you are having thoughts of suicide, or your self-harm has gotten too severe, or won't stop bleeding. Seek help for this behaviour. Avoidance. Avoiding not only your home environment's stressors, but other stressors such as school work is typical. Isolation. As you cannot invite friends over, this is easy to fall into.

Setting boundaries for your well-being

Define your personal space. Don't allow your parents to dump their trash into your room. Setting clearly defined boundaries for your personal space is essential for your well-being. You may do this by getting rid of anything that doesn't belong to you from your space, and donating it or giving it back to who it belongs to. Make a space that is your own, and try your best to de-hoard it. Look after your space, not allowing anything of anyone else's to spill across into it.

Be prepared to distance yourself. This can be challenging if you are under 18 or don't have the money saved yet to move out, but making small changes and preparing for the distance is a critical first step to distancing yourself. Start saving money from a part-time job. Look into youth shelters if your home is harming your health. Stay with friends or other family, when possible. This can help you as time goes past to get your stuff together. Look into laws about moving out from home under 18 in your country.

Communicating effectively with your parent

Anticipate the nature your parents may exhibit. Might one of your parents be a better person to talk to? Could the conversation lead to your harm? If your parents are physically or emotionally abusive as well as neglectful, be cautious when approaching such topics. Be prepared for denial. Your parents will often deny what you are saying, so don't be shocked if they do. Don't be shocked if your parents dismiss your feelings or become defensive. Anticipate whether your parents will be angry or sad, and prepare for the conversation based on what you know about your parents. They're your parents, after all.

Express your feelings using calm, non-blaming language. Using "I" statements rather than immediately jumping to blaming them may allow them to listen to what you have to say. You want to be heard, so making sure you communicate in a way that your parents will listen is essential. Discuss its insidious nature, and how loving, well-intentioned parents can unknowingly pass it on to their children. Be clear that it isn't a blame or accusation. You don't want to be denied of the conversation right off the bat, so be sure to clarify that you're only discussing the topic for everyone's benefit rather than to blame anyone,

Try to show empathy by listening to your parents' side. Listening to their side without immediate judgment may be difficult, but is an important step toward healthy communication. Allow them to explain the issues from their point of view, and listen whole-heartedly. Show that you are listening by practising active listening and empathy. Try to ask questions to show that you care about their side. Ask your parents about their own childhoods. This can offer some perspective on why they do what they do and also shows them that you care about their wellbeing.

Think about involving a third party in the discussion. Having someone with you can help ease any discomfort of being alone with your parent. Invite a therapist, counsellor, family member, or friend to join the meeting. Select someone you trust who can also help diffuse any tension, if needed. This is helpful if you know your parent is going to become angrily defensive.

Choose the right times to talk. Finding the right time involves finding a time that isn't too hectic, along with avoiding times filled with tension. Find a calm time to have your discussion when you are not too busy, and your parent isn't either. Have the conversation in person. Having a difficult conversation like this over text or phone can cause misinterpretations. You need the body language and tone cues to properly communicate.

Address the neglect. Make it clear what you are communicating about, continuing to follow the other steps also. Be clear with your parent, whilst not being too blaming. Don't allow conclusions to be drawn from what you've said that you weren't intending. It can help to draft what you want to talk about in writing, and discuss it with someone else, such as a therapist or trusted friend or family member, first to decide how it comes across. Stick to the facts, and avoid sounding as if you are blaming your parents. Focus on how it has affected you emotionally and physically, being cautious not to sound accusatory. Starting the conversation with something like, "Hi Mum, the state of the house has led to my isolation from friends and I want to do something about it with your help" can help you sound less accusatory, be willing to take on part of the responsibility which shows initiative your parent will appreciate.

Building a support network

Reach out to trusted friends, family members or teachers. Finding people to confide in about your situation is necessary for your mental health. These people can offer emotional support, and advice or even physically help you with your situation. Show them pictures of your housing situation for an additional layer of understanding. They may not anticipate quite how bad it is if you don't do this. Don't hesitate to ask these people for help. If they can't help you, they can tell you that. Asking for help shows great strength, not weakness.

Join support groups or online communities for children of hoarders. Joining these can help offer real-life advice and experiences with other people who fully understand your situation. Groups such as r/ChildrenofHoardersCOH on Reddit can offer you support and advice about your housing situation. This can also help with the feelings of isolation. Knowing others face the same issues as you is a great way to fight these feelings. Seeing success stories of people fixing their hoards or getting out of their childhood homes can give you hope for the future.

Share your experiences with others who may understand or have been through other forms of neglect. These people can offer emotional support beyond the level that friends who haven't been through anything have. You may even find out that one of your friends also deals with the same issues.

Managing feelings of guilt and responsibility

Remember that hoarding is a mental health issue. It isn't your responsibility. It wasn't your fault that the house ended up the way it did. Your parents are mentally ill, whether or not they choose to admit that to themselves. You can't be to blame for an illness that has harmed you more than anyone.

Let go of guilt for not being able to fix the problem. It isn't, and never was, on you to fix this. You deserved a well-kept home from childhood, and you can't be expected to clean an entire house all by yourself. If your parents make you feel this way, remember that it isn't the truth. Affirmations can help with this. Things like "it wasn't my fault I was neglected", and "I can move past this in time" can help you to feel better and more secure in yourself.

Recognise that your efforts to cope are making a difference. You are doing enough, by following any of these steps, you are consciously trying to make things better for yourself. Thats huge! This is an extremely challenging situation, and you are strong to try to cope with it, even though you shouldn't have needed to be this strong.

Seeking professional help and resources

Consider seeing a therapist familiar with family-related trauma. Talking to a therapist or counsellor about your home issues is necessary for your well-being and emotional health. Seek out a therapist or psychologist who specialises in this area if you can, or if not find yourself a school therapist or social worker. If you can't get access to a therapist, consider youth hotlines which have trained youth workers ready to talk 24/7.

Explore books, videos, articles, and websites about hoarding. Seeking more information about your situation is a good idea, as the more knowledge you have on the topic, the more likely you will be able to break free from it.

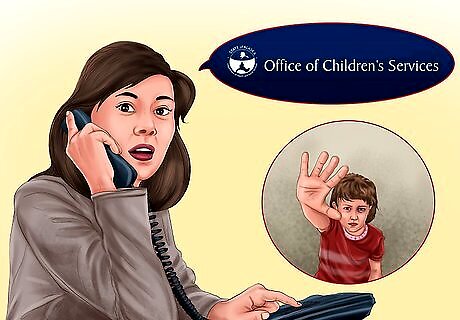

Look into local organisations that help families affected by hoarding. Look up local organisations on the internet, or ask around on forums. You could also ask your therapist or teacher if they know of any organisations that can help you.

Creating a safe and healthy living environment

Declutter and organise spaces you can control, like your room. Try your best to go through your things and get rid of those that don't belong to you, or you don't use. You need to be able to let go of things to avoid falling into the same patterns as your parents. Donate any clothing or items that could be used by someone else. Throw out anything too dirty or destroyed to be useful. Have a friend over to help you clean your room once you get it to a point where you feel comfortable doing so. You'd be surprised how many of your friends would want to help you to clean.

Remove safety hazards, such as blocked exits or dangerous piles. Rearrange your house to remove safety hazards. You can have a parent help you with this, just explain to them the need for your safety and they might understand. If they don't, try to safely clear exits and remove any piles that could topple onto someone.

Try to keep any spaces you use yourself, clean. Having your personal space clean and not full of other people's things is essential for your well-being. It may be a long process, but cleaning the areas you use will help you so, so much in your journey. Areas to consider trying to get to a point of cleanliness or usability include: Your bedroom. This is the most important. Always prioritise your own bedroom. The toilet you use. Not being able to safely and cleanly use the toilet is a horrible experience. Make sure to remove toilet rolls and any random clutter from around your toilet. The family bathroom. This is essential. You need to be able to clean yourself, brush your teeth, shower and perform basic daily routine. You can't do so in a hoarded bathroom. Try to scrub down the basin, keep the bath or shower in working order and remove the clutter from the room. The kitchen, if possible. It would be ideal if you were able to clean your kitchen too, so you can cook and feed yourself and your siblings. However, kitchens are often quite large and VERY messy in hoarded houses, so it's understandable if you don't prioritise this.

Developing healthy routines

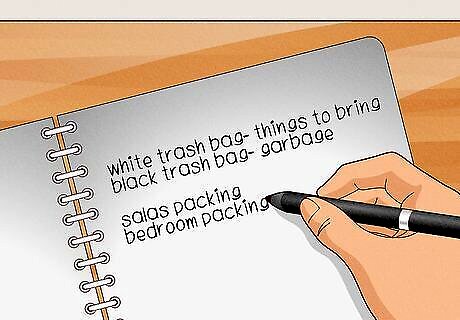

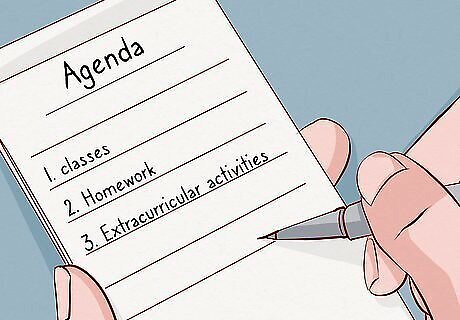

Create a daily schedule. It should include time for self-care, schoolwork, and hobbies. Having routines in your life is key to breaking out of the chaos that is your house. Write yourself a reasonable routine incorporating all the basics and try your best to stick to it.

Develop a regular bedtime routine to improve sleep and overall well-being. Don't stay up cleaning to unhealthy hours of the night. Sleep is much more important, as without it you won't be able to do as much anyway, and the detrimental effects to you mental health and cognition just aren't worth it. Consider taking melatonin supplements at a set time every day.

Set small, manageable goals to build a sense of structure and accomplishment. Writing out new to-do lists whenever you have a new task to complete will help with the overwhelm your house instils in you. By breaking down tasks into smaller steps, you make yourself more likely to complete more by better understanding the task.

Make time for cleaning yourself and your space. Build a time into your routine to shower. Keeping your personal hygiene good is absolutely essential. Don't allow yourself to fall into bad habits, you must continue to keep yourself and your space clean. Create time every day to clean your room or another area. It doesn't need to be for long, but chances are your room will immediately fall back into old patterns as you haven't learnt the skills to keep it organised. Organise your clothing and items at least weekly. Reorganising your things so that they make sense to you and are in places you remember is very helpful. Don't allow yourself to put off folding your washing, for example. Do it when you can, don't let it spread across your room. Change your bedsheets every week. You likely don't remember to do this, so make sure to add this to your weekly schedule.

Comments

0 comment