views

X

Research source

Analyzing the Complaint

Read the complaint thoroughly. If you are sued for appropriation of name or likeness, you must first understand who is suing you and why. Take note of the name of the person and the publication for which they are alleging that you appropriated his or her name or likeness. Check the location of the court in which you are being sued. If it is far away from you, look at the rules for personal jurisdiction and find out if the court has jurisdiction over you. If you believe the court doesn't have jurisdiction over you, say so in the first thing you file with the court – typically your answer to the lawsuit. If you don't assert this objection in your first court filing, the court will assume that you've waived the issue and you won't have the ability to bring it up later. If the court is far away from you, venue also may be a problem. While personal jurisdiction refers to the state in which the plaintiff must file his or her lawsuit, venue refers to the particular county or court location. Like personal jurisdiction, any objection to venue is something you must raise in the first document you file with the court. The person suing you also must have standing to sue. Generally, any invasion of privacy claim, including appropriation of name or likeness, is viewed as a personal claim. This means only the person whose privacy was invaded has the right to sue. Relatives generally can't sue on someone else's behalf, and the lawsuit can't be carried on by the estate of someone who died. However, right to publicity claims may survive a person's death under certain circumstances.

Gather information. You will need information about the published material for which you're being sued. Look up the post, page, or article that has caused the lawsuit. Even if the plaintiff has attached copies or screen-caps, looking it up on your own will help you understand the context. If the problem was the result of a mistake or misunderstanding, you may be able to clear this up with the plaintiff outside of court and avoid a lawsuit entirely.

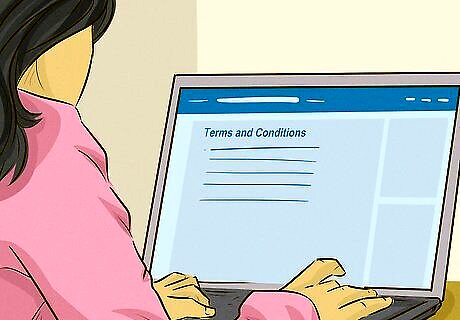

Search for releases. If you can find a release form permitting your use of the plaintiff's name or likeness, you have a complete defense to the lawsuit. If the publication that forms the basis of the complaint was a post on social media, the terms and conditions of the website itself may help you. Social media sites typically require users to allow others to share posts and comment on them. If the lawsuit concerns your use of a photo obtained from somewhere else, such as a stock photo, read carefully the releases for those services and the terms to which you agreed when you signed up for the service. If you operate a website or business that has used the plaintiff's name or likeness in some way, they also may have signed some sort of release form that allows you to use their name or likeness. For example, suppose you run the local grocery store and have included a picture of the winner of the county fair's watermelon-eating contest in your produce ads. That winner has now sued you for appropriation. However, if she signed a release that allowed photos of her participating in the contest to be used by the fair and its sponsors. Since your grocery store sponsored the fair, you have a complete defense that the plaintiff authorized your use of the photo.

Study your state's law. Each state's law defines appropriation somewhat differently and requires the plaintiff to prove certain elements. You must know your state laws requirements to fully analyze the allegations set forth in the complaint. If the plaintiff has not included all of the elements required by your state's law, you may be able to get the complaint dismissed. Generally, the plaintiff must allege – and ultimately prove – that you used some protected attribute of her identity, such as her name, image, or voice, for an exploitative purpose without her consent. Which attributes of a person's identity are protected vary from state to state. For example, California law protects a person's name, likeness, voice, signature, and photograph. However, Florida law only protects a person's name, likeness, and photograph. Pay attention to the attributes your state protects, and make sure the plaintiff's allegations match up. For example, if your state doesn't protect people against the appropriation of their voice, and the plaintiff alleges you have misappropriated her voice in an audio file saying "That's great watermelon!" in your advertisements, she has failed to state a claim under your state's law. Different states also have different standards for how a purpose qualifies as commercial. Typically there must be a direct correlation between the profits you derived and the use of the plaintiff's name or likeness.

Check the statute of limitations. If your state's statute of limitations has passed, the plaintiff is no longer allowed to sue you. Like personal jurisdiction and venue, you waive any objection to the passage of the statute of limitations unless you mention it in your first filing with the court. The statute of limitations provides a deadline for filing a lawsuit after the incident has happened. The clock generally starts ticking from the moment the offending material was published. Each state's statute of limitations for filing an appropriation of name or likeness claim varies widely, but it will generally be between one and six years.

Contact the plaintiff. In many situations you can talk to the person who has sued you and attempt to resolve the dispute out of court. For example, if the use was simple error, you may be able to get out of it with a public retraction – although typically the plaintiff will also expect some amount of monetary compensation. Keep in mind that appropriation claims differ from other invasion of privacy claims in that they are designed to compensate people for the use of their name or likeness for commercial purposes, rather than protect their interest in being left alone. Even though the person has already filed a complaint, you still can suggest using a mediator to resolve the matter more efficiently. Most courts have lists of approved mediators, and some courts have programs available to provide free mediation of pending civil suits. Provided the person suing you is not famous, you may be able to get out of the lawsuit fairly easily if you offer the same amount of money you normally would pay a model, spokesperson, or other commercial actor.

Arguing an Exception

Look for statutory exceptions. In addition to exceptions under the First Amendment, many states have statutory exceptions. You can find state law resources by searching online or by visiting the public law library in your local courthouse. In all states, exceptions are made for news and commentary or for creative works. These exceptions are based on the First Amendment. Some states also have statutes that specifically exempt news reporting or legitimate commentary of current events, particularly on the internet. For example, if you wrote a commentary on your blog expressing your opinion about gay rights, and included a picture taken at a gay pride parade, your use of that photo typically would be protected under an exception should someone in the photo sue you for appropriation. Creative works loosely based on real events also are protected. For example, if you wrote a historical novel about events in your town during the 1960s, but used some real names of political figures during that time, your use of their names typically would be protected under the exception if one of those people were to sue you for appropriation. In most states, this exception is an affirmative defense, which means you have the burden of proving the elements of that offense. For example, California law provides an affirmative defense for creative works, provided the artist or creator proves either that the creative work adds something to the plaintiff's name or likeness, giving it a new meaning, or that the value of the work itself doesn't come primarily from the value of the plaintiff's name or likeness.

Consider hiring an attorney. If you intend to argue your use fits into an exception, you may benefit from hiring an experienced First Amendment or media law attorney. Your state or local bar association will have a directory of attorneys licensed to practice law near you. Often these directories are available on the bar association's website, and you can search for attorneys who practice in particular areas. Look for attorneys who have experience defending against misappropriation or other invasion of privacy cases. Nonprofit organizations dedicated to First Amendment issues also will have legal resources available.

Claim the appropriate exception. If your use falls within a Constitutional or statutory exception, you can state this defense in your answer to the complaint. Keep in mind that just because you raise this defense in your answer, you don't have to argue it at trial – if the case even gets to that point. Stating the defense in your answer merely preserves your right to argue it later on. If you believe your use falls into one of the exceptions – either those recognized under the First Amendment or those included in your state's law – you should assert that defense as soon as possible.

Collect evidence to support your claim. If you are asserting an exception, you typically bear the burden of proving that it applies to your use. Context matters a lot with defenses against appropriation of name or likeness claims. If you're arguing one of these exceptions, you must be prepared to prove that your use falls into that exception.

Arguing Incidental Use

Learn what qualifies as incidental use in your state. Each state typically has specific criteria that must be met to claim your use qualifies as incidental use. Your state's definition of incidental use may be found in law or described in court cases decided by your state's appellate courts. Ask the librarian at the public law library in your local courthouse to help you research the law on incidental use of someone's name or likeness. The key to remember here is that there must have been some meaning and purpose behind your use of that particular person's name or likeness. If no such intent exists, you may be able to argue incidental use. For example, if you post a photo of someone along with a news article or commentary related them, and then that photo appears in an advertisement for your website, it typically would be considered an incidental use. The photo is advertising your website and its content with the intent of bringing readers to your site and is unrelated to the person who appears in the photo. However, keep in mind that this line isn't always clear. Sometimes this use could be considered exploitative, such as if you intentionally use a photo of someone in your advertisements that you know is provocative or will draw attention to your website, but have little or no content related to that person on the website itself. Some states such as Florida offer a similar exception, in which the plaintiff appears in a photograph solely as a member of the public. For example, suppose you use a photo of the crowd from a baseball game to illustrate a blog post about your town's baseball team, and one of the members of the crowd happens to be a local celebrity. If the local celebrity sued you for appropriation of her likeness, your use most likely would fall into this exception – provided the exception is recognized by your state's law.

Consider hiring an attorney. An experienced media attorney can help you craft your incidental use defense. Typically you can go to the website of your state or local bar association and search a directory of licensed attorneys. Look for attorneys who list media law or privacy law as among their areas of practice, but focus on defense attorneys rather than plaintiff's attorneys. In addition to checking your local bar association's listings, you might check on websites of organizations such as the Reporters Committee for Freedom of the Press, which are dedicated to assisting with First Amendment issues.

Review the context of your use. Typically you can claim incidental use if the plaintiff's name or likeness appeared in connection with advertising of your own work. Other uses also may be incidental, such as a photo of the plaintiff accompanying a news article or commentary in which he or she is featured. For example, a photo of the owner of a local grocery store would be considered incidental if it accompanied a blog post discussing plans to demolish the store to make way for a new shopping center.

Claim incidental use. You can claim the defense of incidental use in your answer to the complaint. Emphasize the lack of intent behind the use that the plaintiff claims constitutes misappropriation of his or her name or likeness. Even if you did benefit from using the plaintiff's name or likeness, you typically aren't liable for compensation to the plaintiff if that benefit wasn't your primary motivation in using his or her name or likeness.

Gather evidence to support your claim. You have the burden of proving your defense that your use was incidental and not appropriation of the plaintiff's name or likeness. When arguing incidental use, evidence of the context of the use will be key. For example, if you used a photo of the plaintiff in connection with a news article, copies of the article demonstrate that use of the photo was incidental to the article itself.

Comments

0 comment