views

Reading the Basics

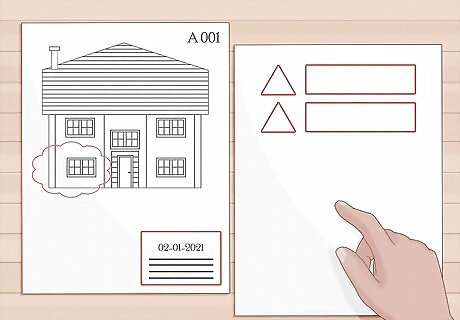

Read the cover sheet. This will contain the project name, the architect's name, address, and contact information, the project location, and the date. This page is very similar to the cover of a book. Many cover sheets will also include a drawing of the finished product, showing you what the house will look like after it is constructed and landscaped.

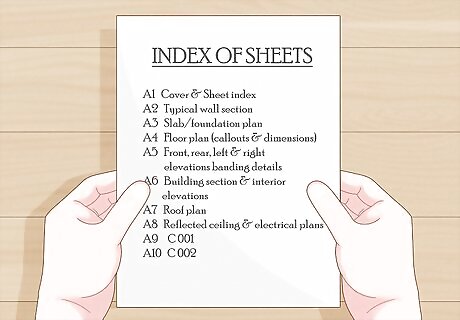

Read the plan index. These pages will include an index of plan sheets, and sometimes their contents. It also will include an abbreviation key, a scale bar with the plan scale indicated, and occasionally design notes.

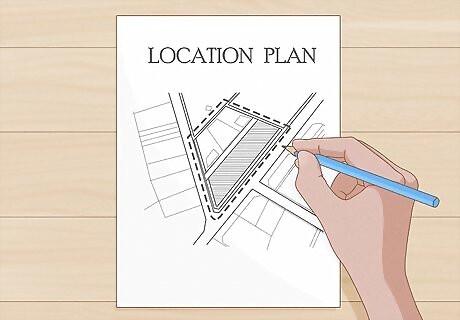

Read the location plan. This will have an area map, with an enlarged location map, usually giving enough information to locate the project site from nearby towns or highways. This sheet is not found in all sets of plans.

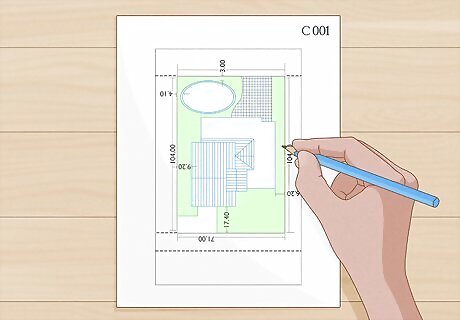

Read the site plans. These pages usually are numbered starting with a "C", such as Sheet "C 001", "C 002," and so on. The site plans will contain several sheets which show the following information: Topographical information. This will provide the builder with information regarding the topography, or the slopes or flatness, of the site. The demolition plan. This sheet (or sheets) will show the structures or features which will be demolished on the site prior to grading for construction. The items which will not be demolished, such as trees, will be noted in the keynotes. The site utility plans. These sheets will indicate the location of existing underground utilities, so that they can be protected during excavation and construction.

Reading Architectural Sheets

Know that you should never scale a drawing. If you cannot locate anything on the drawing with the dimensions given, get more dimensions from the Architect.

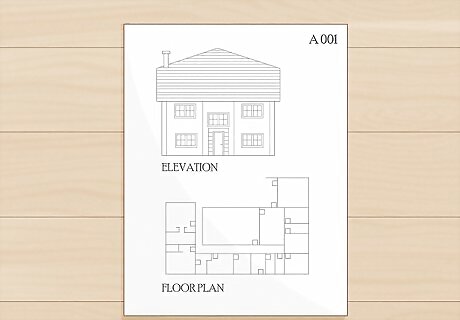

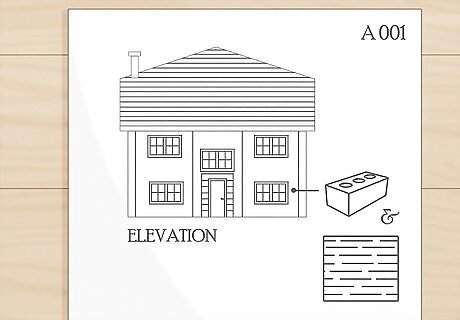

Understand the architectural sheets. These sheets will usually be numbered "A", such as "A 001", or A1-X, A2-X, A3-X and so forth. These sheets will describe and give measurements for the floor plans, elevations, building sections, wall sections and other oriented views of the building design. These sheets are broken up into many parts that make up the construction document that you will need to understand. The parts you'll need to know are described in the steps below.

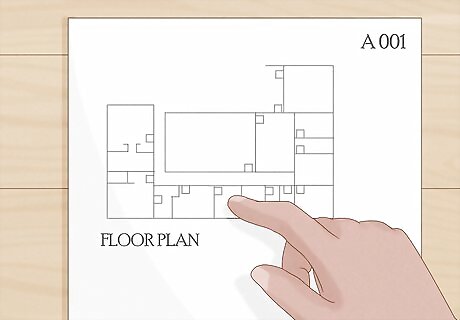

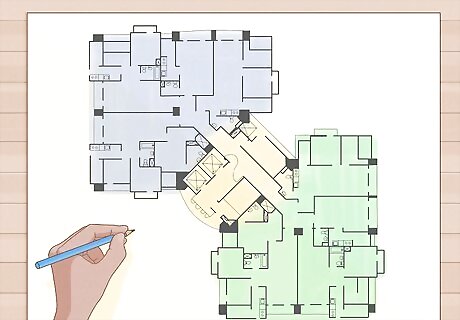

Read the floor plans. These sheets will show the location of the walls of the building, and identify components like doors, windows, bathrooms, and other elements. There will be dimensions noted as distances between, or from center to center of walls, width of openings for windows and doors, and changes in floor elevations, if the floor is multilevel. Floor plans consist of various levels of detail depending on the stage of the project. At stage D (planning) drawings may show only the major features of the space. At a tender stage, drawings will be more detailed, illustrating all features of the space at a larger scale to allow a contractor to price the job.

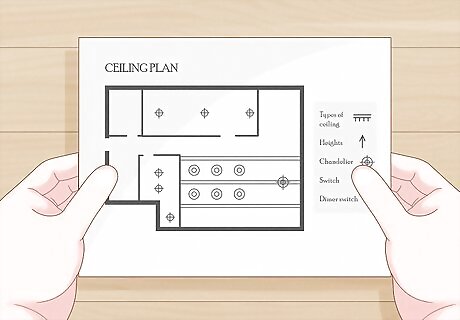

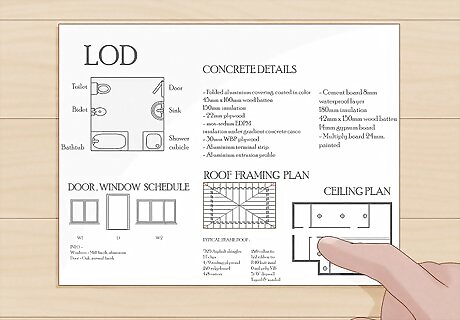

Read the ceiling plans. Here, the architect will show the types, heights, and other feature of ceilings in different locations in the building. Ceiling plans may or may not be depicted for residential design projects.

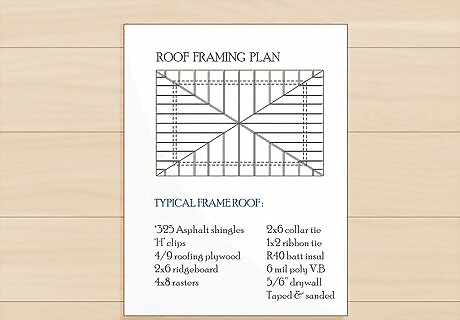

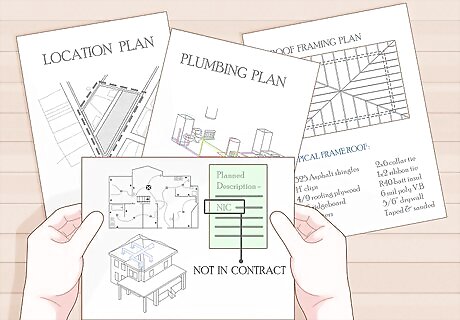

Read the roof framing plan. These pages will indicate the layout for joists, rafters, trusses, bar joists, or other roof framing members, as well as decking and roofing details.

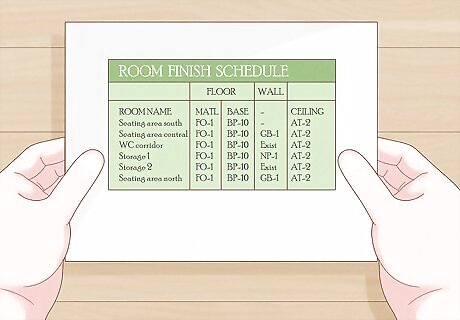

Read the finish schedule. This is usually a table listing the different finishes in each individual room. It should list paint colors for each wall, flooring type and color, ceiling height, type, and color, wall base, and other notes and details for constructing the finish in areas listed.

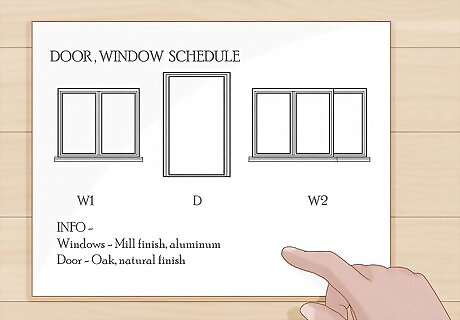

Read the door/window schedule. This table will have a list of doors, describing the opening, "hand" of doors, window information (often keyed off of the floor plan, example, window or door type "A", "B", etc.). It may also include installation details (cuts) for flashings, attachment methods, and hardware specifications. There may also be a separate schedule for window and door finishes (although not all projects do). A window example would be "Mill finish, aluminum", a door might be "Oak, natural finish".

Read the remaining details. This may include bathroom fixture layouts, casework (cabinets), closet accessories, and other elements not specifically noted on other sheets. Such as, but not limited to: concrete details, door and window details, roofing & flashing details, wall details, door details, deck to wall details and others. Every project is different and may or may not include what other projects have. The Level Of Detail (LOD) is determined by each Architect for each project. The growing trend is for Architects to have more, rather than less detail, because the Contractors then have less guesswork and can more easily understand what to include and what to price. Some builders may or may not have comments about the LOD, but that has no relevance to what the licensed Architect who is designing the project feels is necessary to properly explain the design.

Read the elevations. These are views from the exterior, indicating the material used in exterior walls, (brick, stucco, vinyl, etc), the location of windows and doors from a side view, the roof slopes, and other elements visible from the exterior.

Reading the Remaining Plans

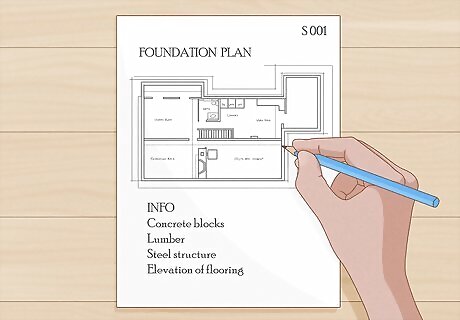

Read the structural plans. The structural plans usually are numbered beginning with "S", as in "S 001" These plans include reinforcement, foundations, slab thicknesses, and framing materials (lumber, concrete pilasters, structural steel, concrete block, etc). Here are the different aspects of the structural plans that you will need to read: The foundation plan. This sheet will show the size, thickness, and elevation of footings (footers), with notes regarding the placement of reinforcing bars (rebar). It will note locations for anchor bolts or weld plate embeds for structural steel, and other elements. A footing schedule is often shown on the first sheet of structural notes, as well as notes regarding the reinforcing requirements, concrete break strength requirements, and other written statements for structural strengths, and testing requirements. The framing plan. This will indicate the material used for framing the building. This may include wood or metal studs, concrete masonry units, or structural steel. The intermediate structural framing plans. These are used for multistory construction, where each level may require support columns, beams, joists, decking, and other elements.

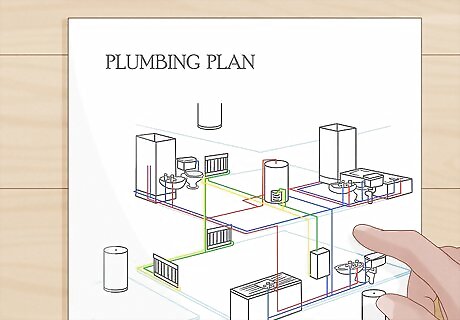

Read the plumbing plan. Plumbing drawing pages are numbered beginning with "P". These sheets will show the location and type of plumbing incorporated in the building. Note: often, home design documents do not include plumbing plans. Here are the parts of the plumbing plan that you will need to read: The plumbing rough-in. This sheet will show the location of pipes which are to be "stubbed up" to connect the plumbing fixtures to water supply, drain/waste, and vent systems. This is rarely incorporated into a residential set of documents, such as for a single family residence. The plumbing floor plan. This sheet will show the location and type of plumbing fixtures, as well as the route pipes will be run (overhead or through walls) for potable water and drain, waste, and vents. These plans are included although most architects (for single family homes) already indicate the location of the plumbing fixtures on their floor plans.

Read mechanical drawings. Mechanical pages are numbered beginning with "M". This sheet or sheets will show the location of HVAC (heating, ventilation, and air conditioning) equipment, duct work, and refrigerant piping, as well as control wiring. This is rarely indicated for single family homes.

Read the electrical plan. The electrical drawings are numbered beginning with "E". This sheet (sheets) shows the location of the electrical circuits, panel boxes, and fixtures throughout the building, as well as switchgears, subpanels, and transformers, if incorporated in the building. Special pages found in the electrical plan pages may be "riser" details, showing the configuration of power supply wiring, panel schedules, identifying specific breaker amperages and circuits, and notes regarding types and gauges of wires and conduit sizes. Some of this information may or may not be included in single family home documents.

Read the environmental plans. These are also known as BMP (Best Management Practices) drawings. This sheet will indicate protected areas of the site, erosion control plans, and methods for preventing environmental damage during construction. There may be details in the BMP drawings showing tree protection techniques, silt fence installation requirements, and temporary storm water drainage measures. The requirement for a BMP plan originates under the environmental protection department of your local, state, or national governing authority. This may not be required, depending on the Authority Having Jurisdiction for single family homes.

Know that all plumbing, electrical, and mechanical drawings are diagrams. Dimensions are rarely given and it is the responsibility of the builder to coordinate the placement of the utility so as to conform with the building code and the Architectural drawings. Be sure plumbing is located so that it matches up with the desired location of plumbing fixtures. Same goes for electrical wiring for power outlets and light fixtures.

Gaining a Deeper Understanding of Architect's Drawings

Learn how to lay out a building footprint from architectural plans. To do this, you will have to locate the element of construction you are reviewing to implement a portion of your work. If you are laying out the location of the building, you will first look at the site plan for location of existing buildings, structures, or property lines so you have a reference point to begin measuring to your building footprint. Some plans simply give a coordinate grid position using northings and eastings, and you will need a "total station" surveyor's transit to locate these points. Here is what you'll need to do to lay out a building footprint from the plans: Lay out your building on the site by either the above referenced plan or the measurements given on the site plan. Measure to locations, preferably corners, on one side of the building, and check for any "checkpoints" to verify the accuracy of your layout. If you cannot absolutely establish an exact building line, you may have to suppose the location is correct and continue. This is widely accepted in cases where the site is very large, allowing for tolerance, but on a crowded lot or site, the location must be exact. Establish the elevation you will work from. This may be a height relative to a nearby roadway, or an elevation determined from sea level. Your site plan or architectural floor plan should have a bench mark(a bench mark refers to some item, such as a manhole lid or survey waypoint with a known elevation) elevation or a "height above existing grade" as a starting point. Use your plan to measure the location of each corner of the building, including offsets. Remember what exact element of construction you are using for your layout. You may mark an outside wall line, a foundation line, or a column line, depending on the type of construction and the most practical element for making subsequent measurements. For instance, if you are building a structural steel building with I-beam columns which require setting anchor bolts to secure them, you may begin your building layout with the centerline of these columns, where if you are building a wood-framed residential structure with a monolithic slab floor, the edge of the slab would be your best choice for the initial layout.

Reference the description of various sheets to find an element of construction you are going to use in the work you will perform. Plumbers use the Architect's floor plan to locate walls so the pipes they stub up will be concealed inside the wall cavity when the building is constructed, then use their plumbing floor plan to find out what types and sizes of pipes are required to service a particular fixture.

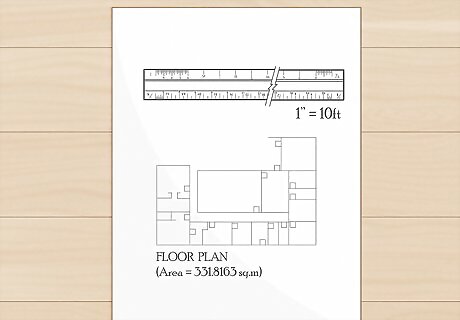

Use the dimension scale where measurements are not provided. As a rule, architectural plans are drawn to a "scale". An example would be, 1 inch (2.5 cm) equals 10 feet (3 m) (1"=10'), so measuring between to walls on the plan sheet means for each inch, the distance is 10 feet (3.0 m). A scale rule will make this much easier, but be careful to match the rule scale to the plan's scale. Architects often use a scale of fractions, such as a 1/32 scale, engineers usually use an inch per foot scale. Some plans or details are not to scale, and should be marked "(NTS)".

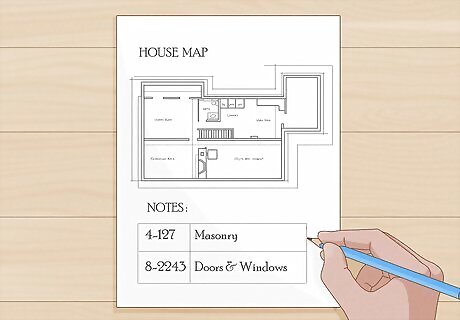

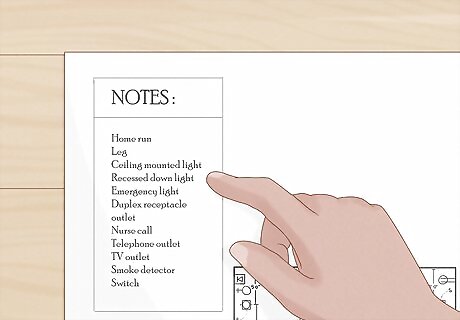

Read all the notes on a page. Often a particular element has special considerations which are more easily described verbally than drawn, and notes are a tool the architect will use to illustrate them. You may see a table of notes on the side of a sheet, with numbers identifying the note location on the plan (a number with a circle, square, or triangle around it) and a corresponding numbered statement describing the situation on the side of the sheet. Sometimes there may be a single sheet or several sheets of Numbered Drawing Notes that consolidate all or most of the drawing notes for an entire set of drawings. Many Architects organize these numbered notes into a CSI (Construction Specifications Institute) method utilizing 1-16 or even more Divisions that categorize the drawing notes into subsections. For instance: a note "4-127" may refer to a type of Masonry, as Division 4 represents Masonry. A note 8-2243 may refer to a window or door component, because Division 8 is Doors & Windows.

Learn to recognize the different types of lines the architects and engineers may use. You should have a specific keynote table for section of plans, and this will provide information on the abbreviations, symbols, and specific lines used in each section of the plans. An example would be that the electrical plans, a circuit may have the "home run" "leg" (the wire going from the first junction box in a circuit to the panel box (the power source) highlighted or in darker ink than other circuits, and exposed conduits may be indicated by a solid line, and concealed conduits by a dotted or broken line. Because there are many different line usages indicating different type walls, piping, wiring, and other features, you will have to see individual plan page "key notes" to understand them.

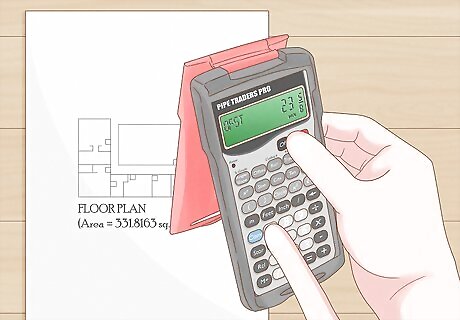

Use a Builder's Calculator to add dimensions when determining distances on your plans. These are calculators which add feet and inches, fractions, or metric measurements. Often, an architect will not give a measurement to a specific plan item, from a baseline such as the "'OBL" (outside building line), so you will need to be able to add the distances each feature which has a measurement provided, to get the total distance. An example would be finding the center line of a bathroom wall to locate the potable water pipe stub up. You may have to add the distance given from the OBL to the living room wall, then the distance to a hallway wall, then across a bedroom, to the bathroom wall in question. This might look like this: (11' 5) + (5' 2") + (12' 4")= 28' 11.

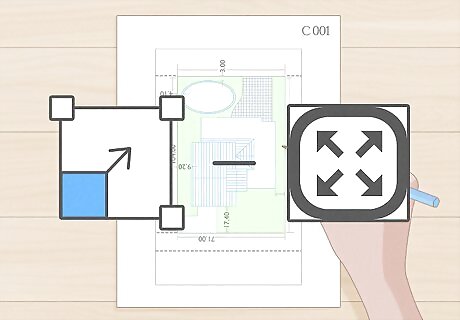

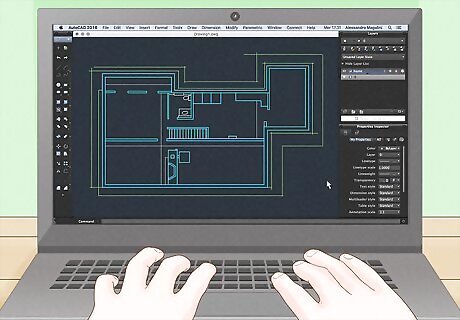

Use CAD (Computer Assisted Design) building plans. If you have a set of architectural plans in an electronic form, as on a CD, you will need a version of the original "cad" program which created it to open the files. "AutoCAD" is a popular, but very expensive, professional design program, and the designer will usually include a "Viewer" on the disc which you can install on your computer to view files, so that actual plan pages appear on your screen, but without the full program, you cannot manipulate design components or change the drawings. However, most Architectural firms know how to save their CAD and other computerized files as a PDF, which they will normally e-mail to you and you will be able to open and view (although not alter, as the Architects are responsible for the integrity of their work).

Learn how to handle architect's plans. These sets of documents are often very large sheets, about 24" X 36", and full construction sets may include dozens, or hundreds of pages. They are either bound or stapled on the left edge, and allowing them to be torn from the bindings, ripped apart by mishandling, laid out in the sun to fade the ink, or left in the rain can make them difficult to use. These documents can cost hundreds of dollars (US) to replace, so try to protect them, and have a flat, wide, protected work surface to unroll and read them on.

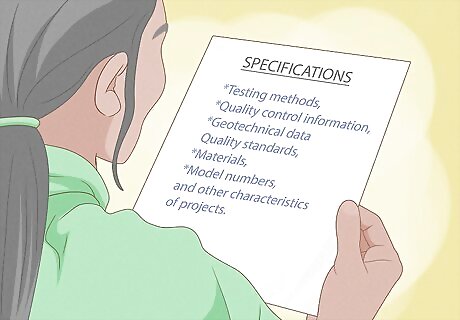

Read the specifications. Specifications are usually printed and kept in a binder, and they list descriptions of methods and materials used in the project, as well as testing methods, quality control information, geotechnical data, and other information useful in building the project. However, some Architects do include the specifications on the drawing sheets (to insure that the specs will not be misplaced). Specifications are the architect's way of indicating the quality standards, materials, model numbers, and other characteristics of projects. Even single family homes often have specifications. Specifications are traditionally arranged in numbered sections, typically Division 1-16, although these numbers have expanded considerably during the last decade. Many Architects number their paragraphs so that they can cross-reference actual verbiage from the specifications onto their drawings using the paragraph numbers, which improves the coordination of the various trades.

Look for notes and symbols referring to "alternate bid items", "Owner Optional Upgrades" and "addenda." These may indicate portions of work which are incorporated in the Architect's drawings, but not necessarily in the builder's contract to construct, supply, or install. "NIC" is an abbreviation for Not In Contract, which means a certain item will be put in a certain place by the owner after the project is finished. "OFCI" or "GFCI" (Owner Furnished, Contractor Installed, or Government Furnished, Contractor Installed) indicate the item is supplied by the customer, but installed by the contractor. Read and understand all abbreviations used in your plans.

Revisions.Architects may issue addenda, which are changes made to the documents after they have been released for bidding. Many Architects locate a blank section, often in the lower right corner of their sheets, just above the sheet number, reserved for a list of Revisions. Revisions are often numbered and enclosed within a triangle, octagon, circle or other consistent symbol. To the right of each revision number will be the date of the revision, then to the right of that, a brief description of the revision. Then on the drawing area of the sheet, that numbered symbol will appear in the area where the revision was made, often along with a "revision cloud", which is usually depicted with a lumpy series of arcs resembled a cartoon cloud, encircling the area in which the revisions where made. This allows everyone to understand exactly what has changed. Also, the Architect will normally issue an e-mail summarizing the revisions contained in each addendum, sent simultaneously to the Owner and registered bidders. It is then up to the various bidders to convey this information change to their subcontractors and material providers.

Comments

0 comment