views

Rhyming in Poetry

Write freely. When you're faced with a blank sheet of paper and want to fill it with poetry, it's best to avoid rhymes entirely in the earliest draft. Trying to start with rhyme is a good way to end up with cat-hat-bat rhymes and bad poetry. Instead, write free verse or journal freely and see what comes up. What are you trying to say? What is the concept of your poem? Start with a line or an image that strikes you and start producing the raw material from which you might build a more structured formal rhyming poem.

Find a guiding line. After you've written for a while, turn your piece of paper over, or open a new word processing document. Take your favorite line from your free write and write it at the top of the page. What struck you about this? What's good about it? Use that as a guide for a possible poem. Explore the premise or image that the line contains. Often, a free write will end on a particularly good line you might want to use as a starting place. Look to the last few sentences for a guideline.

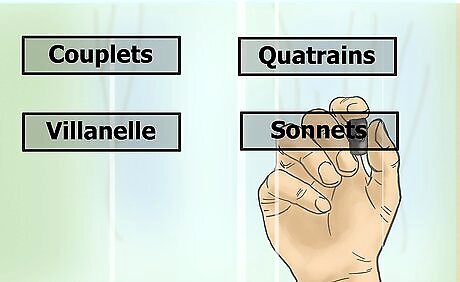

Consider an appropriate form for the poem. If you want to write a formal poem, familiarize yourself with common rhyming forms and the uses of those forms to pick one that will work best for the theme of your poem. Couplets, or heroic couplets, refer to any poem in which the poem rhymes every two lines. Used by poets from Milton to Frederick Seidel, couplets can create a sense of gravity and the epic. A poem featuring quatrains, or four-line stanzas, may rhyme in a basic alternating rhyme scheme (ABAB) or other schemes. Ballads and songs are traditionally written in quatrains, making it a good form for telling stories or spinning musical tales. In a villanelle, whole lines from the first stanza are repeated from one three-line stanza to the next, with the first and last line in the stanza rhyming, giving the poem a sense of inevitability, as if the poem were something you cannot escape from. Sonnets are poems of 14 lines with a semi-complicated and pre-set rhyme scheme, with about 10 syllables or five beats per line. Most sonnets written in English are generally either Petrarchan (ABBA) or Shakespearean (ABAB, with a rhyming couplet for the last two lines). Sonnets often deal with rhetorical themes or "arguments," featuring a turn in the poem somewhere after the eighth line.

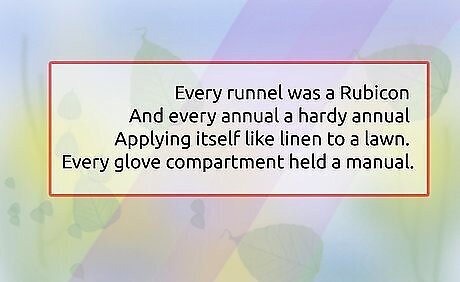

Use rhymes to create surprise and add complexity to the poem. Your rhymes should serve the poem, your poem should not serve the rhymes. Never rhyme for the sake of rhyming, or start a poem hoping to rhyme. This will result in forced "cat-hat-bat" types of rhymes that will undercut the poem, rather than add to it. Paul Muldoon, an Irish poet, has a surprising rhyming style. His poem "The Old Country" is a crown of sonnets that features deft and surprising rhymes: Every runnel was a Rubicon / and every annual a hardy annual / applying itself like linen to a lawn. / Every glove compartment held a manual.

Read contemporary poetry for inspiration. It can be difficult to write contemporary poems that rhyme well if you're only familiar with Shakespeare, Wordsworth, and Dr. Seuss. There's no reason to keep Twitter, Frosted Flakes, and Lil Wayne out of your poems because your verses are choked with "thous". Find some contemporary poets who employ rhymes in fresh but traditional ways: Check out Michael Robbins, who in his great poem "Alien vs. Predator," creates a long string of wacky and associative musical rhymes from the cereal aisle: He's a space tree / making a ski and a little foam chiropractor. / I set the controls, I pioneer / the seeding of the ionosphere. / I translate the Bible into velociraptor. Read Ange Mlinko, a contemporary poet skilled enough to pull of rhyming potatoes with tattoos to end her poem "The Grind": spooning up Aphrodite / to Greek porticoes, and our potatoes, / and plain living which might be / shaken by infinitesimal tattoos. "Casualty" by Seamus Heaney manages to be colloquial, narrative, musical, and incredibly easy to read. He's a great poet who makes it seem effortless: And raise a weathered thumb / Towards the high shelf, / Calling another rum / And blackcurrant, without / Having to raise his voice David Trinidad--a poet who often writes about the pop culture of the 1960s--shows mastery of the villanelle form with his hilarious and poignant "Chatty Cathy Villanelle": Our flag is red, white and blue. / Let’s make believe you’re Mommy. / When you grow up, what will you do?

Rhyming in Songwriting

Write the melody first. It's very difficult to set pre-existing rhymes and words to a melody after the fact. Most songwriters find it much easier to compose the melody and then go about composing a set of lyrics that fit in with the tone and the structure of the song. Many songwriters find it helpful to sing nonsense syllables or whistle to figure out the melody and establish a base form for you to fill with words. Go with whatever technique works best for your process. Bob Dylan, considered by some to be one of the greatest songwriters ever, often wrote words first. Give it a shot.

Learn to "turn" a phrase. A popular and important technique in country music especially, a good song will often "turn" a phrase, or use a line to mean more than one thing throughout the course of a song, when used at different times. In Kacey Musgraves' "Blowing Smoke," the phrase "blowing smoke" is used at different times to refer specifically to waitresses on break smoking cigarettes, and also to boasting of quitting someday, referring to both the job and the habit. It's an effective technique that changes the meaning but not the words.

Use as few words as possible. Avoid overloading your lines with too many words, making your song a tongue-twister that can be difficult to sing. As you compose, use words judiciously, leaving out more than you put in. A simple and quick rhyme that's simple can be much more effective in a song than a lot of "poetic" words. In "The Butcher," Leonard Cohen makes a brief and devastating rhyme out of drug use: I found a silver needle. I put it into my arm. / It did some good, did some harm.

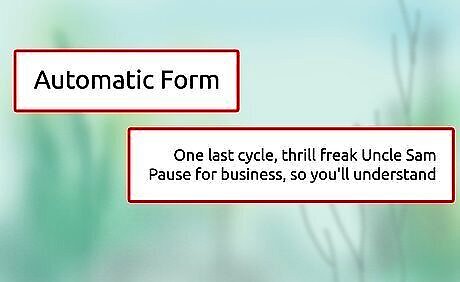

Try automatic forms. Novelist and Beat writer William Burroughs pioneered a method of writing that involved cutting up rhyming words and phrases and throwing them into a bag. Try doing the same and removing phrases at random to collage together a tapestry of weirdness for your song. Music is amenable to that kind of writing. The Rolling Stones employed this technique for their song "Casino Boogie": One last cycle, thrill freak Uncle Sam / Pause for business, so you'll understand.

Rhyming in Hip-Hop

Listen to the beat and find your flow. Spend a lot of time with the beat you're trying to rap over, internalizing the sound and the rhythm of it, to find your flow before you start coming up with lyrics. Like you write the melody in a traditional song first, you have to find the flow first in a rap song. Some rappers will do a similar "nonsense word" technique, just spitting rhythmically without saying actual words. Try to record yourself doing this, even if it sounds silly, because something good might leap out. Good rapping is as much about flow as good rhymes. If you stay on beat, it's better than if you lose the beat and try to force awkward or overly complicated rhymes into the structure of the song.

Freestyle. Like you might do a freewrite to start getting poetry out, trying some freestyles is a good way to get started and find a starting line to use for a song. Or, if you're Riff Raff, just record your freestyle and call it a song.

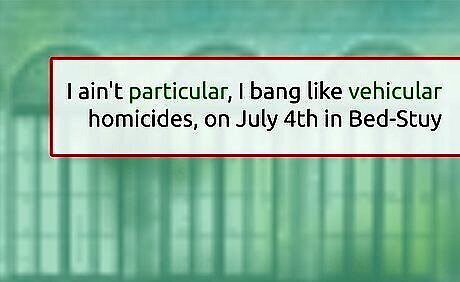

Learn and use enjambment to your advantage. There's no rule that rhymes need to come at the end of each line, especially in hip-hop, or that the rhyming word needs to be the end of the sentence. Vary the placement of the rhymes. Embed rhymes internally and skip rhymes entirely to add variation to your flow. You don't have to rhyme at the end of each line to rap well. In "Duel of the Iron Mic," GZA creates a particularly strong break in the lines, using a well placed and surprising break in the beat to surprise us: I ain't particular, I bang like vehicular / homicides, on July 4th in Bed-Stuy

Listen to expert hip-hop rhymers for inspiration. Familiarize yourself with the greats, listening to a wide variety of rhymers to begin learning the craft. Listen to: Nas, who jumped on the scene as a teenager with his classic album Illmatic, which featured these lines: It drops deep as it does in my breath / I never sleep, cause sleep is the cousin of death. Eminem, whose intricate and well-crafted rhymes have made him a bona-fide king of the rap game: I'm Slim, the Shady is really a fake alias / to save me with in case I get chased by space aliens. Rakim, one of the most influential MCs in hip-hop: Even if it’s jazz or the quiet storm / I hook a beat up, convert it into hip-hop form.

Rhyming Well

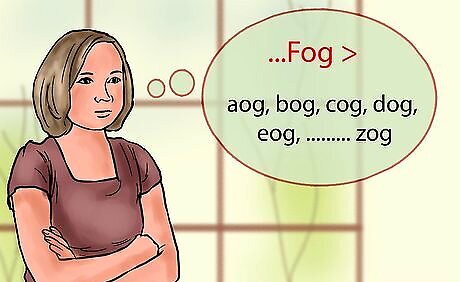

Think of all the rhyming possibilities before settling on one. Change the prefix of that word to every letter in the alphabet. For example, if you needed to find a word that rhymes with, "fog," start at A and go "aog, bog, cog, dog, eog, ... zog," until you reach Z. Write down every word that is real, such as "bog," "cog," and "dog" and only select the most interesting choices. If one doesn't work, alter the first line to serve the poem or song. When going through the alphabet, inserting an R or an L into short words will often make another word. So if you were looking for a rhyme with cat, you could find bat as well as brat; fat, as well as flat and frat. It's a trick of the trade.

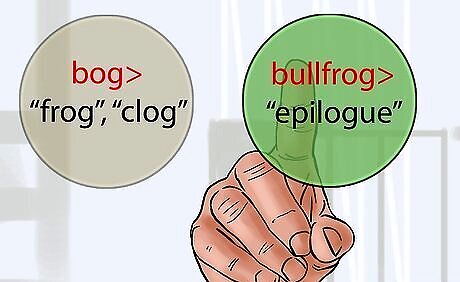

Bury rhymes in longer words. Use other multi-letter prefixes you know to build more complicated words with which to rhyme. First letters won't always cut it. For example, "frog" and "clog" are real words that rhyme with bog. Try multisyllabic words like "bullfrog" or "epilogue."

Only choose appropriate words. If no word works, consider changing the keyword to a synonym of that word, or abandoning your rhyme scheme for a line or two. For example, you could substitute "mist" for "fog," but only use rhymes to improve the poem or song, never to rhyme for the sake of rhyming.

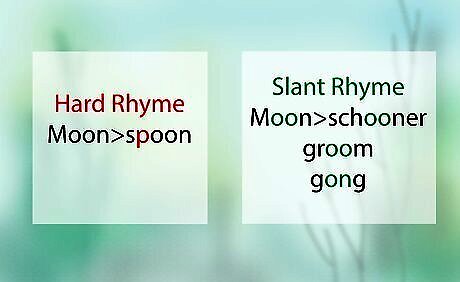

Use slant rhymes. Hard rhymes, sometimes called true rhymes, "sound" right to our ear because of identical vowel and consonant combinations. "Moon" and "spoon" are hard rhymes because of the long "o" sound and the "n." Slant rhymes are rhymes in which either the vowel or the consonant in similar, creating a kind of echo of the rhyme, and giving you all kinds of possibilities. "Moon" could be slant rhymed with "on" or "schooner" or "groom" or even "gong". Slant rhymes offer complexity and surprise to a regular series of hard rhymes.

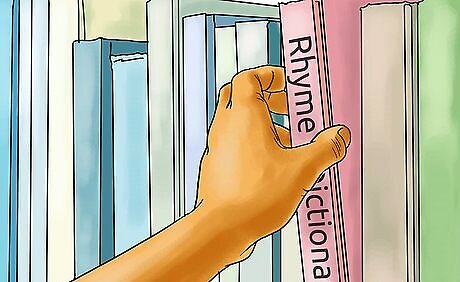

Consult a rhyming dictionary. It's worth it to invest in a good rhyming dictionary to consult, or you can find it online. It's not cheating to use a dictionary for rhyming just as it isn't cheating to use a thesaurus while writing. Studying up on good rhymes will also build your vocabulary, giving you a larger collection of words to use in future songs, poems, or freestyles. A rhyming dictionary may help you find rhymes you might not think of right away. It may offer not only rhymes, but also near rhymes (words that sound to the ear like they rhyme, even though they really don't).

Always use rhymes to move the piece forward. Rhyming is a technique that writers and musicians can use in their compositions to emphasize words and images and unspool surprising and complicated poetry. Use it to add little bits of color and texture to your work, but not as the reason for creating it. If something needs rhymes, use them well. If no, leave them out.

Comments

0 comment