views

Understanding the Disability

Recognize that a lot of what you know about disability may be wrong. Consider each "fact" you know about a given disability, and ask yourself where it came from. If the answer is "pop culture," then that information may not be accurate. Disabled people themselves are usually the most reliable sources on what it's like to live with a disability. Medical books/websites (such as WebMD, Healthline, or Verywell Health/Mind) and accounts from people with disabled loved ones are good secondary sources. Turn researching a given disability, and the tropes associated with it, into a project.

Choose disability-friendly language. People with disabilities are often very careful about what terms they prefer to use. What do they call themselves, and what do they want not to be called? Respecting their language preferences will please disabled readers, and encourage non-disabled readers to do the same. For example, the word "cripple" is considered offensive while words like "amputee" or "person who uses a wheelchair" are more neutral. While some communities have reached a clear consensus on language (such as deaf people preferring to be called "deaf people" instead of "people with deafness"), other communities have not. Read what these people have to say.

Read from the disabled community. What are their lives like? How do their symptoms affect their experiences? What sort of character would they love to read a book about? Understanding their perspectives can help you build a believable character with a disability like theirs. Look for popular hashtags like #ActuallyAutistic or #DeafPride.

Recognize that disabled people are very diverse and have different experiences. Many disabilities are a spectrum: for example, many blind people are not completely blind, and simply have some degree of low vision. Some disabilities are stronger on some days than on others, based on stress and other factors. The spoon theory covers how some people need to budget their energy.

Remember that people with disabilities learn and grow. For example, a girl with Down syndrome will be able to do much more at age 15 than she could at age 5. Disabled characters, including characters with intellectual/developmental disabilities (IDDs) will be able to learn new things and gain skills. They will simply do so at their own pace. The idea that someone with an intellectual or developmental disability is "forever a child" is a misconception. They'll become adults, even if adulthood looks a little different with a disability, and they'll gain skills (even if it's late sometimes).

Writing Disability Realistically

Read personal accounts from people who have the disabilities you wish to portray. What are their lives like? Where do they struggle? Are there any gifts that come with their disability? What do they feel are common misconceptions? See if any people with disabilities would be open to being interviewed. There is no substitute for face-to-face time with real people. If you are polite and clear, many disabled people are willing to offer advice and answer questions. Try asking questions via social media. Remember that disabled people are diverse. No two people are exactly alike (whether it's two blind people or two people with fetal alcohol syndrome). Symptoms can vary between individuals.

Write a character first, and the disability second. Every person is a unique individual, with interests, strengths, and flaws, if they have a disability or not. Although a disability is a character trait, a disability is not a defining character trait. It will influence their life, but their personality (likes, dislikes, relationships, skills) is far more important. Spend plenty of time developing them as a person. Most disabled people are quite ordinary: they wake up, eat breakfast, go to work, and live fairly average lives. Portraying disabled people as "beautiful tragedies" ignores the fact that in fact, most people with disabilities are not any more or less tragic or beautiful than anyone else.

Explore what goes on in your disabled character's head. Some writers make the mistake of portraying people with cognitive disabilities as "irrational" or "mysterious" beings whose thoughts and behavior make no sense. The reality is that everyone has a reason for what they do, and the clarity of disabled people's thoughts is often underestimated. The way of thinking may be very different than others, but if observed closely, there are logical reasons behind every behavior. Nonspeaking people and people with intellectual disabilities still have thoughts, regardless of whether they can communicate them clearly. If your disabled character isn't the main character, that's fine. You can still attribute thoughts to them, and have the main character recognize what's going on in their head. (For example, "Lucy visibly relaxed as soon as the Christmas music came on. She loved happy song lyrics, so I kept a playlist of songs with good messages.")

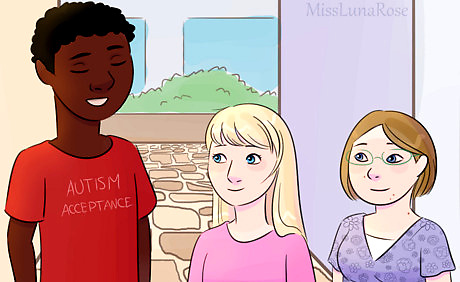

Consider intersectionality. People with disabilities come in all shapes, colors, backgrounds, socio-economic levels, and so on. Readers have been calling for diversity, and an easy way to satisfy that need is to write more than one deviation from the privileged "norm" at a time. Try writing a black woman with cerebral palsy, an autistic Arab-American Muslim woman, a chubby boy with Down Syndrome, or a blind lesbian. Keep in mind that "forced diversity" is not a thing. People can belong to more than one minority group in real life, and chances are, you may even know some people who belong to various minority groups. Not every disabled person is white, male, and/or straight, so there's no need to make every disabled character in your story reflect these traits. As long as you handle diversity in a respectful way, there is nothing "forced" about it.

Recognize that illness recovery (when possible) is often an arduous task. This may require medication, therapy, and/or lifestyle adjustments. It may take years of hard work. Recovery is not a straight line, and there will be good days, bad days, and relapses. Mental illnesses such as depression and psychosis are sometimes possible to recover from completely, with enough time and effort. This often involves a combination of pills and therapy, along with a loving and supportive environment. Some conditions and illnesses have no cures. In this case, the individual's best outcome is to manage their symptoms and understand their limitations better. Some disabilities, such as deafness and autism, are not "illnesses" but simply conditions. The ideal outcome is to find ways to live comfortably and accommodate the disability. Recovery isn't always permanent. In some conditions (such as mental illnesses), it's possible to recover, be okay for a while, and then relapse—sometimes for no obvious reason.

Stay far away from pseudoscience. Some of the things you may have been told about disability could be false, so avoid repeating them without fact-checking. Avoid repeating myths or making up your own. Don't speculate that real-life disabilities are caused by mystical means or by things you personally dislike (such as pollution, vaccines, or technology). These are real people. Some "therapies" are actually scams. Avoid endorsing a therapy without checking whether experts endorse it or whether there are stories of danger (such as people being traumatized or physically harmed).

Recognize that in real life, getting disability accommodations can be very difficult. Many parents of disabled children, and disabled adults, have to fight for necessary accommodations. Depending on the organization's policies, this can be an exhausting process. Assessments may be stricter if the organization is disability-unfriendly or wary of spending money. This means that people with disabilities or their parents, who may already be overtaxed, may have to jump through a lot of hoops. Sometimes disabled people are required to undergo assessments. They may or may not know that you are supposed to fill out forms describing how you are on a "bad" day, not a good day. People may be re-assessed every year, even if the disability is lifelong. These assessments may be overly strict, with the possible result of turning away people who truly need help. Faking a disability for accommodations would actually take a ton of energy. (The idea of fakers also makes it more difficult for real disabled people to get the help they need.)Did You Know? Accommodation stories vary a lot. So, if you want to write about an awful place that looks down on people or a wonderful place that happily offers accommodations, both can be realistic. Think about what's right for your setting and story.

Portray seeking help and self-advocacy as positive things, not as signs of weakness. Admitting that you have a problem and need help (especially involving medication) is a very difficult task. Many disabled people struggle with the idea that it's "all in their head." You can help people with disabilities by showing that it's okay, or even a sign of strength, to ask for help. This can help them have the courage to do this in real life. Stay far away from stereotype that mental illness medications are for the weak. These medications may be the only way to have a decent or functional life. For some people, a diagnosis and the subsequent accommodations are an enormous relief. Getting help instead of "toughing it out" can make life much easier, and it's better than getting frustrated or blaming themselves for struggling with an issue they don't have a name for. Show disabled characters asking for help, and non-disabled characters asking the disabled character what they need. This can encourage the idea of people with disabilities asking for and receiving help when they need it.

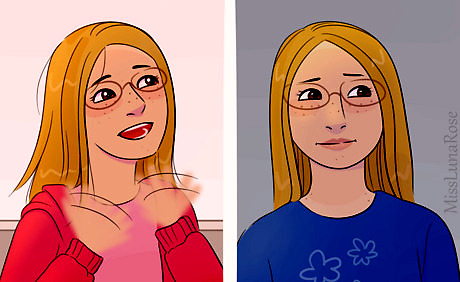

Try exploring the tension between meeting one's needs and blending in. People with disabilities (especially teens or people new to the workforce) may feel insecure about being different and not "passing" as non-disabled. If disability is a significant part of the story, then this may be an interesting dynamic. Some people with visible disabilities try very hard to emphasize that "I'm just like you." Others don't. Some people with invisible or semi-visible disabilities are very nervous about others knowing they are disabled. Others choose not to care what others think of them, and spend less energy on blending in. Some people can "pass" as non-disabled, while others cannot.

Consider how the character has handled ableism. Almost all disabled people experience mistreatment related to their disability (including before a disability is diagnosed). Many have difficult childhoods, and get treated differently from their peers. Whether they experience constant ableism or are mostly shielded from it, it will affect them, their coping skills, their ability to ask for help and trust others, and how they handle conflict. Consider your character's past and how it has shaped them. They may have dealt with... Bullying, being left out Feeling alone, not seeing others like them in real life or in the media Being talked down to, or talked about as if they weren't there Trying and failing to perform to non-disabled standards; seeing adults' disappointment Watching "helpful" adults give up on them when their disability isn't magically cured by the power of love Enduring abuse to "cure" deafness or autistic traits More.Keep in mind: Their experiences with ableism will depend on lots of things. Their environment, such as the community, their family, authority figures, and medical attitudes, can influence how people treat them. For example, supportive adults might be able to prevent or quickly interrupt bullying. The disabled person may use coping skills like charisma or "masking" to avoid mistreatment. Ableism is different when you can "pass" as non-disabled versus when you can't. And a lot of it is luck.

Avoiding Stale Fiction Stereotypes

Recognize the value in telling a unique story. Many stories about disabilities follow similar formulas, portraying disability as a burden or tragic flaw while failing to make the character three-dimensional. Telling an original story helps change negative narratives and could inspire disabled people and their loved ones to enjoy and share your story. Assume that people with the same disability as your character will be reading the story. What type of impression do you want to make on them? Will your story help them feel good about who they are? Family members and peers of disabled people will also read this story. How do you want to influence their perspectives and behavior?

Give your disabled character something to contribute. Many writers portray characters with disabilities as one-dimensional background characters with nothing useful to do. Disabled people aren't helpless. Let your character have meaningful skills and positive points to their personality. Show that the world is better off with them around. An interesting character has agency and pursues goals in the story. Even a minor character can contribute something small to the plot: the observant autistic boy who notices that something is wrong, or the sister with cerebral palsy who has incredible computer skills. Avoid having characters refer to the disabled character as a burden, tragedy, etc. (unless you wish to show that this character is cruel)

Let the disabled person be a character in their own right. Sometimes writers make the character exist only to reflect upon another character (to show how nice/evil the character is, or to burden them with a poor disabled family member). Or the character may be a Manic Pixie Dream Girl/Boy, who only exists to further the other character's development.

Name the disability. Just as queer-baiting (hinting at queerness without confirming it) is frustrating, hinting at but refusing to mention a disability is frustrating to disabled readers. Do them a favor and outright say the name of the disability. Your disabled readers will love it, and your non-disabled readers might learn a thing or two. Aliens and fantasy creatures can have the names of human disabilities. The same disability existing in two worlds isn't going to be the least improbable thing in your story.

Avoid the mystical disability stereotype. This is the idea that people with some sort of physical difference will always have something bordering superpowers. Examples include autistic people having superior mathematical powers, like in the movie "Rainman", or the idea that blind people have enhanced sensory ability. While authors who write this may mean well, it can have unfortunate implications for real-life disabled people who don't have savant skills or compensatory superpowers. People with disabilities are valuable without superhuman powers. If, however, you want to give your disabled character superhuman powers, make sure it doesn't compensate for the disability. Even better, the power can be unrelated to it (e.g. a Deaf superhero that can manipulate time).

Avoid making disability evil. Some works have one character with a disability: the villain. The villain might be a brainiac in a wheelchair, the autistic monstrosity with no empathy, or the dangerous psychotic person with a mental illness. Most disabled people are no eviler or threatening than your average person, and also want to imagine themselves as awesome protagonists. Let people with disabilities be heroes for once. If you absolutely need a disabled villain, then make several good disabled characters or have the main character disabled. That way, the villain is the exception and not the rule. Otherwise, have no disabled characters at all. No representation is better than stigmatizing representation.

Don't make disability be the problem. Too often, books pose the idea that the person's disability is their key barrier, and they need to overcome their disability in order to be happy. This can be alienating to people who will be disabled for life, and suggests that they cannot be happy unless they become someone they are not. Instead of showing the person becoming less disabled, try showing them learning to handle their disability better, and others learning to accommodate them.

Make characters inspiring because of what they do, not who they are. Most disabled people don't consider themselves heroic for walking or rolling down the street. If you wish to show that a character with a disability is strong, then give them non-disability challenges to face. Maybe they won an election, spearheaded a project, or defeated the supervillain. Avoid falling prey to "inspiration porn," which involves labeling disabled people as inspiring for doing ordinary things. Disabled people don't exist solely to inspire non-disabled people.

Don't let disability stop romance. A common myth is that all disabled people are aromantic and asexual, like children. It is assumed that they cannot fall in love, kiss, or have sex, or that even if they could, they are not desirable. This is incredibly damaging to disabled people's self-esteem and romantic prospects. If your story involves love and romance, then let characters with disabilities be included in that. This helps show that they're desirable and worth dating. A small portion of disabled people are aromantic and/or asexual (just like a small portion of non-disabled people are). If you have an aro/ace disabled character, consider showing other disabled characters who are in love, to make it clear that disability doesn't negate sexuality.

Show that characters with disabilities have adapted. Most disabled people are used to their disabilities, and can function pretty well on a day-to-day basis. (Newly disabled people may still be adjusting.) They have had plenty of time to learn what their body needs and get used to it. In most cases, seeking a cure would be a poor use of time. It would be much more efficient to get accommodations (e.g., support at school, a better wheelchair), and focus their time on projects that use their talents and yield actual results.

Research individual disability stereotypes. How do writers often fail when writing disability? How could you succeed in those areas? Look up tropes, and ask disabled people what annoys them most in the media. Here are some examples of stale stereotypes: Autistic people are often represented as clinical, unfeeling, cold, and/or intensely super-powered. Mentally ill people may be portrayed as intensely creative, or as dangerous people who deserve anything that happens to them. Medication doesn't "cure" ADHD; it is still a real disability even after treatment.

Let your character be disabled at the end of the book. Miraculously curing a disability reeks of lazy writing. Too many characters with disabilities end up cured or dead, suggesting that a happy ending and disability are opposite each other. This message is disheartening to people with lifelong disabilities. Instead, let your character be happy and disabled at the end. A happy disability-related ending could be getting the accommodations they need: an awesome power wheelchair, a fun and helpful new therapy, their dad learning sign language, etc. Or give them a regular happy ending: acceptance into their dream college, a sweet boyfriend, being elected to the Senate, or a group of awesome friends.

Aim to make a positive impact on your disabled readers. Some readers will share the same disability as your character. Others will have similar disabilities. Think about what message you'd like them to take away. What impact should your story have? If your story is accurate with a good message, readers with the disability may start recommending it to each other and their loved ones. This can make a powerful impression!

Comments

0 comment