views

New Delhi: When President Donald Trump announced via a late-night tweet that he would “suspend immigration” to protect U.S. jobs from an economic tailspin caused by the coronavirus, Priyanka Nagar prepared for the worst.

For more than a decade, Nagar, an Indian citizen, had steadily built a life in the United States but she was now back in India, awaiting a visa extension. She and her husband, who works for Microsoft, have applied for green cards. They hung an American flag from their balcony in their home in Washington state, where Nagar had given birth to the couple’s 5-year-old daughter.

But when Nagar read Trump’s tweet posted late Monday, while separated from her family in the United States, the thought of leaving her hard-forged life behind without even a goodbye was devastating, she said.

“I beg the government not to think of us as enemies,” Nagar, 39, a software developer, said. “I want the US to prosper. It has given us so much.”

By Tuesday, Trump had ordered a 60-day halt in issuing green cards to prevent people from immigrating to the United States, backing away from his harder-edged plans to suspend guest-worker programs after business groups erupted in anger at the prospect of losing labor from countries like India.

But as millions of Americans file for unemployment, flooding food banks and hospitals, foreign workers worry that the pandemic will uproot them sooner rather than later.

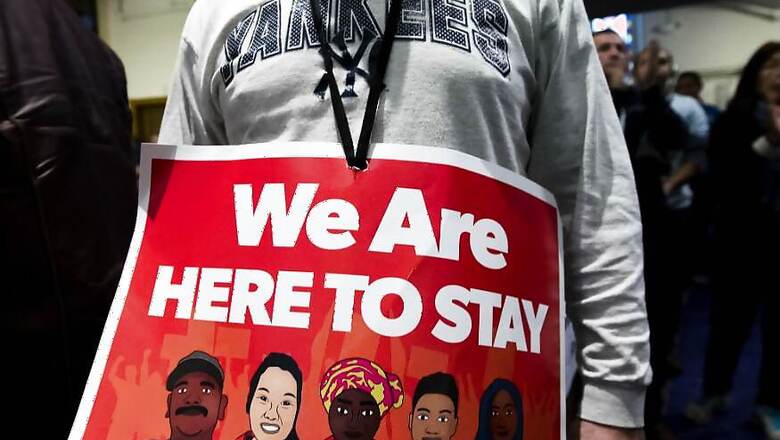

Immigrant groups warn that driven by what they call the Trump administration’s protectionist impulses, the United States could purge some of its most talented workers, cutting into the vibrant multiculturalism that has made the United States such an attractive destination for decades.

“I cannot tell you the panic this has caused in the legal immigration community,” Nandini Nair, an immigration lawyer based in New Jersey, said of Trump’s “upending of life by a tweet.”

Further immigration restrictions could have particularly acute consequences for India, which sends thousands of highly skilled workers to the United States every year and counts a 4 million strong diaspora in the country, representing one of the largest contingents of immigrants to the United States.

Visa programs like H-1B help fill specialty positions at companies like Google, Apple and Facebook. Indian-Americans are some of the country’s most successful and wealthiest immigrants, with a particular stronghold in Silicon Valley’s startup scene.

These days, Harkamal Singh Khural, 34, a software developer living in an Atlanta suburb, said he was barely sleeping. Even if the government did not push him out, he said a volatile job market meant his immigration status was already tenuous.

The company that sponsors his H-1B visa has already let go of half of his team. His two daughters are US citizens, meaning it was possible that his family could get separated.

“I am afraid of losing everything,” Khural said. “This is not really about a job. It is about dreams.”

For now, programs like H-1B are unlikely to be immediately affected by the new restrictions. But Tuesday, Trump left open the possibility of extending the ban on new green cards “based on economic conditions at the time.”

He suggested that he may also introduce a second executive order that could further restrict immigration, brushing aside studies showing that a flow of foreign labor into the country has an overall positive effect on the US workforce and wages.

“We must first take care of the American worker,” Trump said, insisting that newly jobless citizens should not have to compete with foreigners when the economy reopens.

Rights groups say the immigration process has become increasingly complex and frustrating in recent years, with Trump fanning the flames of anti-immigrant sentiment by pushing for an extensive wall along the Mexican border and labeling a group of African nations “shithole countries.”

For Indian citizens, building a more permanent base in the country was never easy.

Most of the 800,000 immigrants currently waiting for a green card are Indian citizens. Because of quotas that limit the number of workers from each country, Indians can expect to wait up to 50 years for a green card since their representation among immigrants is so high in the United States.

Last summer, the Fairness for High-Skilled Immigrants Act, which sought to address the backlog by eliminating country quotas, sailed through the House. But it stalled in the Senate, where critics like Sen. Dick Durbin, D-Ill., argued that the bill would not solve the problem because it does not increase the overall number of green cards.

Many Indian citizens said the back-and-forth was exhausting.

“I likely won’t receive a green card in this lifetime unless the laws change,” said Somak Goswami, an electrical engineer who applied for a green card in 2011. “I have colleagues who came to the US in 2017 and have a green card already. My only fault was I was born in India.”

Analysts said immigration restrictions could strain the delicate but increasingly amicable relationship between India and the United States, the world’s most populous democracies.

In recent months, Trump and Prime Minister Narendra Modi of India have sought to build an even stronger alliance, trading compliments about each other onstage at glittering events in Houston and Ahmadabad, India.

Milan Vaishnav, the director of the South Asia Program at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace in Washington, said, “Any action that appears to infringe on the mobility of Indians or Indian-Americans will be strongly resisted.”

“Suffice it to say, this will not go over well in India,” he said of stricter immigration controls. “Prime Minister Modi has made outreach to the diaspora community in America and elsewhere a cornerstone of his foreign policy.”

In India, Nagar, who is staying with her parents in the state of Uttar Pradesh, said she was trying to remain hopeful, telling herself to “live today and wait for tomorrow.”

But with international airspace largely closed, embassies shut for visa processing and the added stress of immigration restrictions, Nagar worried that the extension of her H-1B visa might be delayed by many more months, prolonging the separation from her family and raising the possibility that they may have to leave the United States entirely.

Over a video call, Nagar’s daughter, a kindergarten student, told her: “Mommy, when the virus dies, you’ll come. I’ll wait for the virus to die.” When video conversations with her daughter end, Nagar said she sometimes lies in bed and cries.

“In the US, you have the whole world working together toward a common goal,” she said. “You cannot find that diversity anywhere else. I love this country.”

Kai Schultz and Sameer [email protected] The New York Times Company

Comments

0 comment