views

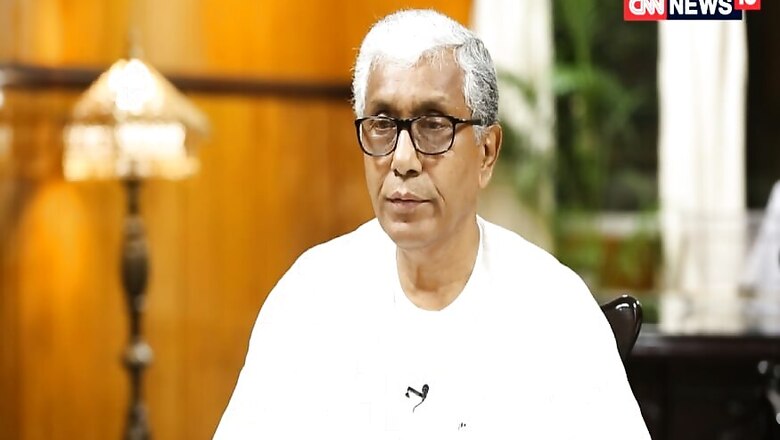

Beyond the personal opportunism, politics of poverty and frictions of race, two ideas are at war in the small north-eastern state of Tripura which will elect a new government next Sunday. The Marxist head of the ruling Left Front, Manik Sarkar, described as the “cleanest and poorest chief minister in the country”, is almost the sole standard-bearer left in India today of a radical alternative to the politics of class, caste and capital.

He may be in danger of being swept away by the saffron wave represented by the BJP in alliance with the Indigenous Peoples’ Front of Tripura (IPFT) and a group of Congress turncoats who flirted with Mamata Banerjee’s Trinamool Congress before finding refuge in the Hindutva camp.

Capturing Tripura would be a major step in fulfilling Amit Shah’s dream of bringing all eight north-eastern states into the NDA’s fold. No wonder the BJP has deployed all its heavy artillery from Narendra Modi to Smriti Irani for the contest for 60 assembly seats. It already rules Assam, Arunachal Pradesh and Manipur; its partners in the North-East Democratic Alliance govern Nagaland and Sikkim. The BJP is also making a strong bid for Meghalaya and Nagaland which are going to the polls this month. A Congress-mukt Mizoram will be the last challenge for Modi and Shah.

Of course, neither Hindutva nor the Marxist revolution that never was is ever mentioned in this battle of ideologies. The ostensible emphasis is on poverty alleviation. The BJP’s Vision Document 2018 promises prosperity while the party panders to local sentiment by saying it will highlight the former royal family’s achievements, rename Agartala airport after its creator, Maharaja Bir Bikram Manikya Kishore Deb Barman, and upgrade it to international status. Sarkar, unique among chief ministers in not owning a house or car and not being guarded by security personnel, seems rather a mild antagonist for a life-or-death struggle that is crucial to the BJP’s ambitions.

Barring five years from 1988 to 1993, his Left Front has been in power since 1978 and dominates the assembly with 51 MLAs. Tripura boasts the country’s highest literacy rate and highest concentration of schools. It claims creditable paddy production, extensive rural electrification and a network of blood banks. But unemployment is high, with more than six lakhs registered as unemployed in a population of about 38 lakhs. That is one grievance. Another is the on-again, off-again tribal demand for a separate state.

The challenge of jobs, capsuled into the popular “Ten-three-two-three” crisis, acquired dramatic poignancy last March when the Supreme Court cancelled the appointment of 10,323 government school teachers. This was a major blow in a small state with few industries where the government is still the biggest employer. Sarkar’s government made the appointments in December 2013 on the basis of “merit” and “need” through an open-interview process without written tests.

There were more than a lakh of applicants and the unsuccessful ones went to court accusing the government of violating the Right to Education Act as well as the National Council for Teachers’ Education’s guidelines. The Tripura High Court ruled in their favour, the Supreme Court agreeing that appropriate recruitment rules were not followed.

The controversy played into the hands of the BJP which holds out the promise of a “one-time relaxation” of appointment norms to save jobs. Prakash Javadekar, the Union Human Resource Development Minister, reportedly told a delegation of Tripura teachers that the Centre would amend the Right to Education Act to help them. Sudip Roy Barman, one of the Congress-to-Trinamool-to-BJP defectors went even further. He is quoted as saying a generous NDA government in New Delhi would save the jobs irrespective of “whether the BJP or the Left comes to power” in Tripura.

The Left Front is hard put to it to counter such magnanimity. “We are a pro-poor government” pleads the CPI(M)’s state general secretary, Bijan Dhar, pointing out that the appointments were made “to help backward sections of society” in accordance with rules that the first Left Front formulated in 1978. The courts haven’t mentioned corruption, he adds. But the courts have frustrated plans to recruit 12,000 “non-teaching staff”, presumably to accommodate the 10,323 teachers threatened with unemployment.

The irony is that while the two sides are fighting ostensibly to create jobs and more than 30 per cent of the inhabitants are tribals, the 297 candidates are among the richest in the land. Of the 35 crorepatis in the fray, 18 are from the BJP, their assets averaging Rs 1.35 crores per head. The average individual worth of the 59 Congress candidates – nine of them crorepatis -- is Rs 53.16 lakhs. The chief minister may be poor and honest but four of his Marxist candidates are worth more than a crore each.

With factions at every stage – among tribals, among unemployed teachers, among legislators – battle lines are somewhat blurred as Sarkar defends India’s last red fort against the saffron assault.

(Mr Datta-Ray is a journalist and author of several books. He has been editor of The Statesman. Views are personal)

Comments

0 comment