Covid-19 a Perfect Opportunity for Indian Airports to Stop Aping Western Models and Turn Atmanirbhar

views

As the coronavirus pandemic wreaks havoc across the globe, aviation has emerged as one of the most impacted sectors. A fear of travelling and a narrative that airports and airlines pose contagion risk has set in. While significant sanitisation measures have been implemented, passengers continue to be apprehensive. Partly because the spread of the virus has been traced back to air travel and partly because if each unplanned interaction can is classified as a random risk, the overall travel experience aggregates to significant randomised risk. Demand has fallen off a cliff and is not likely to recover to pre-Covid19 levels anytime soon. The government’s initiatives on self-sufficiency are commendable indeed. Yet, when it comes to infrastructure design and regulatory models, one is yet to see any changes. Case in point: airports.

Airports continue to force-fit western models and the Indian passenger is paying for it all. Ironically, the pandemic poses the perfect opportunity to revisit the country’s flawed airport development model. A model that has for long ignored the market reality where price sensitivity is high and most city pairs are within a two hour flight of each other. India’s passengers demand efficient airports that are low-cost but high quality and enable folks to fly in and out while minimising time. Instead, we have five-star shopping malls with a jet bridges attached. Lounges, large floor areas, artwork, expensive parking and ‘Chai tea’ worth Rs 150. These items are simply not aligned to the market demand. Rather, these epitomise a mindset where western models have been force-fit in the Indian context. A mindset that completely ignores the unique complexities of the Indian market and one that glosses over the passenger who neither expects nor wants to pay for these features and facilities but is left with no choice.

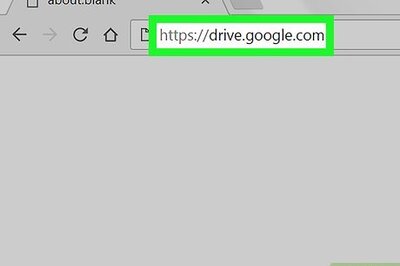

Why this mismatch happens is tied in to both cultural and economic incentives. Culturally, aping the west has become a norm. And no one is questioning it. Economically, in case of airports, the mismatch can be attributed to the current economic regulatory model (which ironically has again aped the west but has selectively chosen the parts that are in complete misalignment with the India market). For instance, currently PPP airports are guaranteed a return on equity of 16 per cent. The process involves the airports submitting traffic projections along with operating expenses, taxes, the cost of capital, any subsidies received and capex plans to the regulator. A target revenue figure is calculated and the gap between the target revenue and actual revenue is recovered via the levy of User Development Fees (UDF) to the passengers. That’s not all, in cases where the airport is unable to secure adequate financing for capex, the funding gap between the financing secured and financing required is again borne by the passengers via airport development fees (ADF).

Consider these numbers: the Delhi airports final project cost was 3.8 times the initial estimate and in case of Mumbai, it was 1.7 times the initial estimate. The cost of these overruns was covered by the flying public. Both airports were allowed to levy development fees to the tune of nearly Rs 3,400 crore. The contribution via fees levied on passengers being 1.2X–1.4X the equity contribution in the case of Delhi and 3.0X–3.2X in the case of Mumbai. Given the recent expansion at Benglauru airport estimated to cost in excess of Rs 10,340 crore and preliminary numbers being floated for Jewar and Navi Mumbai airports, a similar outcome may be assumed. And none of these airports have addressed the core issue which is affordability, efficiency and convenience.

The economic regulatory model also leads to perverse incentives for airports towards spending more. Thus, airports continue to build and most of the investment goes into construction of terminal buildings. Most recent estimates indicate that while investment in excess of $5.5 billion has gone into airports, 55-70 percent of total project costs for airport development spends have gone to terminal buildings. The design and utility of these buildings clearly demonstrate that they are geared towards driving capex rather than driving aviation growth. Many of these are designed with a western context in mind which leads to a huge variation between user experience and design.

Airports make the case that terminal construction costs are capped and regulated but the argument is flawed on many counts. Up until the pandemic, we were witnessing the construction of luxury terminals with amenities to cater to the few but paid for by all; economy-class passengers paying for the lounges they do not use; terminals and terminal areas refurbished, demolished and relocated; commercial vehicles charged for accessing the airport because they use a short strip of road that now comes under the airport premises; private vehicles charged exorbitant amounts for parking — the list goes on.

That’s not all. One would hope that all of this spending by airports is leading to better infrastructure. Yet, on a comprehensive basis that considers the airport system as a whole, our airports are found wanting on many fronts. Consider this statistic: the country saw only two new runways since independence on a net basis. A comprehensive capacity gap looms. This has been flagged in multiple forums but concerns have fallen on deaf years. Our airport system is always only one thunderstorm or rainstorm away from complete disruption. This scenario plays out every year.

The pandemic and the complete decimation of air-traffic have brought up a window of opportunity. But the window may not last long. And as the country speaks about ‘Atmanirbhar’, this must translate to infrastructure projects as well. That is, a focus on solutions that are built for purpose. Built for the India market dynamics and built to fit the needs of the Indian traveller who eventually foots the bill. Force-fitting western models can no longer be the norm. Infrastructure design and regulation requires a revisit.

Satyendra Pandey has held a variety of assignments in aviation. He is the former head of strategy at GoAir. Previously he was with the Centre for Aviation (CAPA) where he led the advisory and research teams. Satyendra has been involved in restructuring, scaling and turnarounds. Has also provided policy inputs and suggestions.

Comments

0 comment