views

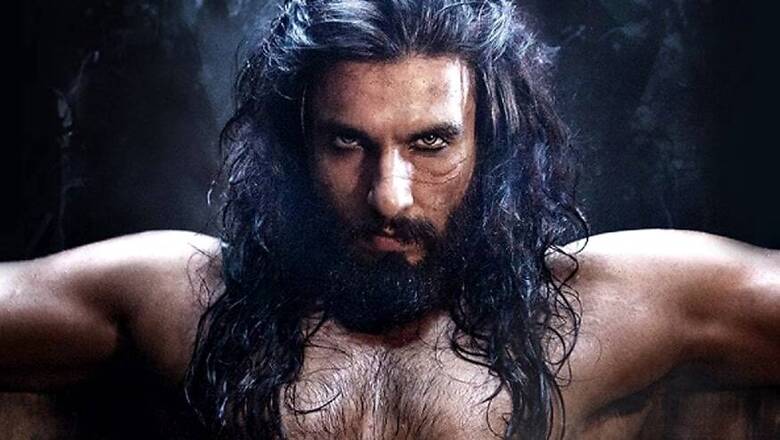

Ali Gurshasp, better known by his regnal name of Alauddin Khilji; let’s pause for a minute (which is way longer than any fringe group did) to consider the man himself as compared to the way he’s been portrayed by Ranveer Singh in Sanjay Leela Bhansali’s Padmaavat.

Singh’s Khilji is shown from the very beginning as an intemperate, sadistic horn dog with no morals and severe impulse control issues. The thing is, people like that usually end up in a prison or a mental institution, not as Sultan-e-Hind. One could point to any debauched ruler in history, but I would argue that those were the later generations of previously established dynasties now devolving into decadence, and they’re usually deposed fairly quickly.

The real life Alauddin, on the other hand, was born to a family of slaves-turned-generals, with no imperial prospects to speak of. When his uncle (and father-in-law) Jalaluddin finally raised himself to the throne at the ripe old age of 70, Alauddin was already an established military commander and administrator of no little skills and abilities, and burgeoning ambitions. Yet in Bhansali’s hyper-stylistic cinema, Ranveer as a debauched Alauddin is shown fooling around with a woman who’s definitely not his wife during his own wedding to Jalaluddin’s daughter, in a not very concealed corner of the marriage venue. The real Alauddin was too shrewd a political animal to indulge himself at such a vital phase in his career, no matter what some apocryphal tale of a wedding rape may report.

Indeed, Alauddin Khilji lusted for a place in history more than any woman (or eunuch general), as evident from his desire of becoming a second Alexander, even issuing documents and prayers for himself in that name. In order to become known as thus, one doesn’t abandon their precariously held capital (Delhi) and go gallivanting off to the desert to capture the queen of a seemingly impregnable mountain fortress. With all due respect to Rajputs (not so much the Karni Sena), the only reason Alauddin besieged Chittorgarh was because of its strategic importance in conquering the rest of Rajputana and not because of some queen from Sri Lanka. That’s the kind of thing you’d find in a film script, not in the annals of conquerors.

It should also be noted that Khilji -- instead of routinely going off on the world’s most awkward pre-Tinder dates, as suggested by the film – spent a lot of his reign in Delhi, formulating administrative, taxation and revenue reforms, which were so effective that several of them were continued by subsequent Mughal and even British rulers. And we all know how much those two groups loved their tax systems.

Then there’s the whole revolt thing. Padmaavat shows a remarkably ill-conceived assassination plot by Alauddin’s nephew which grievously wounds the Sultan and robs him of his mojo just when Padmavati finally does turn up in Delhi. Yeah, none of that happened. In reality, there were at least three attempted coups against Alauddin, which were discovered and thwarted before they could even begin. Alauddin wasn’t injured (or even in any danger) during any of them and in fact, amused himself by coming up with novel methods for execution of the perpetrators.

Interestingly, in order to quell any further thoughts of rebellion, Alauddin (himself a heavy imbiber of various substances) enforced a total prohibition, in his court along with the city and outskirts of Delhi, of not only alcohol but also opiates and cannabis. This last is a bit of a head-scratcher as one would assume a court full of stoned nobles would be more preoccupied with which type of biryani to have for dinner than the plotting of a coup; but what do we know?

Quite a bit actually. Which is why it’s so frustrating that various fringe elements are comparing the Alauddin of Padmaavat to the Alauddunya wad Din Muhammad Shah-us Sultan (to give him his full title) of real life and using it as a reason to take offence. Make no mistake, the real Alauddin was a cruel and ruthless tyrant but he was the cruel and ruthless tyrant that India needed in the 14th Century in order to fend off repeated invasions by the Mongols. Sort of like Winston Churchill in World War II.

And that perhaps was Khilji’s greatest contribution to medieval and thus modern India: he saved us all from the Mongols. Heck, he even constructed Hauz Khas, an artificial reservoir system meant to keep Delhi supplied with water in case of a Mongol siege, so today’s hipsters owe him an enormous debt, or at least a couple of shots.

Admittedly, the Mongols were a pretty cosmopolitan empire who, after subjugating a place and its people, allowed their conquered territories to live and worship in peace, sans any religious bigotry. On second thoughts, can we ask them to come back now?

Comments

0 comment