views

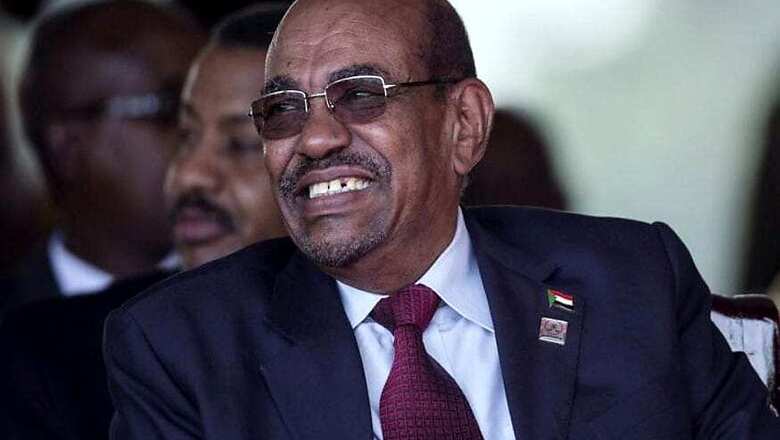

The Hague, Netherlands : South Africa on Friday denied it had flouted international law by refusing in 2015 to arrest visiting Sudanese President Omar al-Bashir, wanted by war crimes judges on charges of genocide in Darfur.

At an unprecedented hearing at the International Criminal Court, Pretoria fended off accusations it had failed in its obligations to the very tribunal it helped found.

There "was no duty under international law on South Africa to arrest the serving head of a non-state party such as Mr Omar al-Bashir," argued Pretoria's legal advisor Dire Tladi.

Despite two international arrest warrants issued in 2009 and 2010, Bashir remains at large and in office amid the raging conflict in the western Sudanese region of Darfur.

He has denied the ICC's charges, including three accusations of genocide as well as war crimes and crimes against humanity.

The deadly conflict broke out in 2003 when ethnic minority groups took up arms against Bashir's Arab-dominated government, which launched a brutal counter-insurgency.

The UN Security Council asked the ICC in 2005 to probe the crimes in Darfur, where at least 300,000 people have been killed and 2.5 million displaced, according to UN figures.

'No immunity waiver'

Pretoria, which had sought legal clarification from ICC judges before Bashir's 2015 visit, argues the Sudanese leader has immunity as a head of state.

There was "nothing at all" in the UN resolution which waived Bashir's immunity, said Tladi.

Therefore Pretoria could not arrest him during his brief visit to South Africa in June 2015 for an African Union summit, despite its obligation to cooperate with the ICC set out in the tribunal's founding Rome Statute.

"The duty to arrest Mr Omar al-Bashir was not as clear as the office of the prosecutor would suggest," added Tladi.

But prosecutor Julian Nicholls shot back that South Africa "had the ability to arrest and surrender him and it chose not to do so."

"All the reasons for not arresting Mr al-Bashir, in the end, simply boil down to that South Africa disagreed with the court's jurisprudence, the law as set out..., so it did not comply."

Several victims of the conflict, who now live in The Netherlands, were attending Friday's hearing in the tribunal in The Hague.

Conditions in Darfur remain "dire," said Monica Feltz, executive director of the rights group, International Justice Project.

The 10 Darfurians who will watch the hearing are "hoping to see that their story is told, and that their voices are heard, and that the international community still cares," she told AFP.

Presiding judge Cuno Tarfusser said the aim of the hearing was to decide "whether South Africa failed to comply with its obligations ... by not arresting and surrendering Omar al-Bashir ... while he was on South African territory."

'Most serious crimes'

The prosecution argues that since the ICC does not have its own police force it relies on member states to help execute arrest warrants.

Without such help, "the court's going to be unable to carry out its most basic function: putting on trial persons charged with the most serious crimes," said Nicholls.

The judges will return their decision at a later date, and may decide to agree with the prosecution's request to report Pretoria to the UN Security Council for non-compliance and eventual sanctions.

But Pretoria's lawyers argued such a move would be "unwarranted and unnecessary," aimed only at casting South Africa "in a bad light."

Although this is the first public hearing of its type, last year the ICC referred Chad, Djibouti and Uganda to the UN for also failing to arrest Bashir. So far no action has been taken against them.

The Sudanese leader was also a guest last month at an Arab League summit hosted by Jordan -- also a signatory to the Rome Statute.

South Africa had moved to withdraw from the court, angered by the case against it.

But it formally revoked its decision last month after its own High Court ruled it would be unconstitutional.

Comments

0 comment