views

X

Research source

Around one percent of the general adult population meets the diagnostic criteria of trichotillomania, with the majority of sufferers being female.[2]

X

Research source

Snorrason, I., Berlin, G.S., & Han-Joo, L. (2015). Optimizing psychological interventions for trichotillomania (hair-pulling disorder): an update on current empirical status. Psychology Research & Behavior Management, 8, p.105-113.

People often start compulsive hair-pulling around the early teenage years, though some people start earlier or later than this. When coupled with depression, hair pulling can result in impairment of functioning in social and work situations.[3]

X

Research source

Tung, E.S., Flessner, C.A., Grant, J.E., & Keuthen, N.J. (2015). Predictors of life disability in trichotillomania. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 56, 239-244.

You may feel helpless when you're in the bind of hair-pulling. But it is a condition that can be treated, and with great success.

Identifying Your Triggers

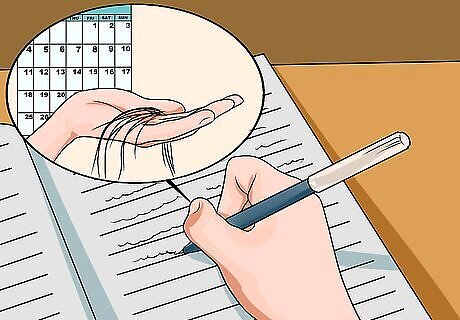

Keep track of when you’re pulling your hair. Consider what kinds of situations cause you to resort to hair-pulling. Do you only do it when you're depressed? Angry? Confused? Frustrated? Understanding what triggers your hair-pulling can help you find other, more positive ways of coping. Carrying ziplock bags and putting pulled hair in the bags will also help you understand how much hair you are pulling out and tracking progress. Over two weeks, jot down every time you catch yourself pulling your hair. Document what happened just prior to the hair-pulling, as well as your feelings. Also, note the time of day and the activity.

Make note of how you feel when you pull your hair. When learning the triggers, try to pin down what could be reinforcing the behavior. If you pull hair when you are anxious and this relieves the anxiety, then the hair pulling is positively reinforced by the feelings of relief. Take stock of how you feel during and immediately after you pull your hair. Knowing this can help you cope because the next time you feel anxious, you can try to find another coping strategy that brings you relief and work to make that your conditioned response to anxiety or your go-to coping strategy rather than hair pulling. There are three distinct phases for sufferers of trichotillomania. Not all sufferers go through each of the three phases. You may experience one or more of these phases: 1.You initially experience tension accompanied by a desire to pull out some hair. 2. You start pulling out hair. It feels really good, like a sense of relief, as well as some excitement. 3. Once the hair is pulled, you might feel guilt, remorse, and shame. You might attempt to cover the bald patches with scarves, hats, wigs, etc. But eventually the bald patches become obvious to everyone and you tend to start hiding at this point. You might start to feel intensely humiliated.

Examine the hair that you’re pulling. Do you pull hair because you don’t like certain kinds of hair? For example, one person might pull hair compulsively when they find grey hairs because they don’t like grey hair and “all greys must go.” One way to work on this trigger is to re-frame your perceptions of those hairs. No hair is inherently bad--all hair serves a purpose. Attempting to change your thought patterns about these hairs can help reduce the urge to pull.

Consider your childhood influences. The initial cause of trichotillomania could be genetic and/or environmental. Researchers see similarities with the triggers for obsessive-compulsive disorder and consider that chaotic, distressing childhood experiences or disturbed early relationships with parents or care-givers might be behind the development of this disorder. One study has shown that over two-thirds of sufferers had experienced at least one traumatic event in their lives, with a fifth of them diagnosed with post-traumatic stress disorder. This has led to speculation that it is a form of self-soothing for some sufferers, a way to cope.

Look at your family history. When tracing the source of your trichotillomania, look at whether you have a family history of hair pulling, obsessive compulsive disorder, or anxiety disorders. There is a significantly increased risk of developing trichotillomania if there is a family history of this disorder.

Developing Strategies to Stop Pulling Your Hair

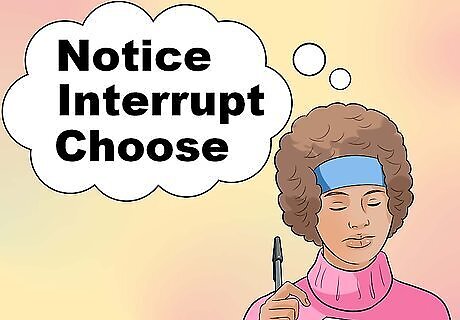

Develop a plan to stop yourself. The "Notice, Interrupt, and Choose Plan" is one strategy that may help you stop pulling your hair. This consists of noticing when you feel like pulling your hair, interrupting the chain of feelings and the urge to pull your hair through listening to positive reminders in your head. Then, you can choose to do something else instead, something that will relax you and calm you.

Keep a journal or a chart of your hair-pulling episodes. Through writing you can get a good idea of the times, the triggers, and the impact of your hair-pulling. Record the date, time, location, and number of hairs you pull and what you used to pull them. Write down your thoughts or feelings at the time, as well. This is a good way of getting the shame out, and of expressing how the hair-pulling is impacting your life in general. When you tally up the amount of hair you've pulled out, this can serve as a reality check on how much hair you're removing; is the result surprising to you? What about the amount of time spent on it, was it more than you thought?

Choose an alternative way to express your emotions. Once you have identified the warning signs and triggers, write a list of alternative behaviors you can do instead of hair pulling. Whatever the alternative behavior is, it should be easy to do and easy to access. Some suggestions for alternative ways of expressing your emotions and feelings include: Taking a few minutes to clear your mind. Drawing or scribbling on paper Painting Listening to music that relates to your emotions Calling a friend Volunteering Cleaning Playing video games. Stretching

Try a physical reminder to make yourself stop. If you’re pulling your hair unintentionally, you may need a physical reminder to make yourself stop the activity. For a physical barrier, consider wearing ankle weights on the arm that pulls, or a rubber glove, to discourage pulling. There are also finger covers and acrylic nails that can help act as a barrier to pulling. You might even have Post-It notes placed in areas where you tend to pull your hair a lot. These can act as other physical reminders to stop.

Distance yourself from your triggers. While it’s likely not possible to eliminate all triggers that compel you to pull your hair, you may be able to reduce some of your exposure. Is your girlfriend the cause behind most of your episodes? Perhaps it's time to reconsider your relationship. Is it your boss who's causing you all this stress? Maybe it's time to find a new career opportunity. Of course, for many, the triggers aren't as simple to identify or get away from; for some, change of schools, abuse, newly realized sexuality, family conflict, the death of a parent, or even pubertal hormonal changes are behind compulsive hair-pulling. These triggers are very hard - if not impossible - to get away from. If it is the case that you can’t get away from a trigger for any of the above or other reasons, continue to work on self-acceptance, retraining your habits and enlisting social support to help you cope with your disorder.

Reduce itching or strange feelings on your head. Use an all-natural oil to soothe the follicles and reduce itching, but more importantly to modify behavior from picking and pulling to stroking and rubbing. Make sure to use all natural products such as a mix of essential oils and castor oil. Try a cooling or numbing hair product to work as a "competing response" during Habit Reversal Training with your therapist. There is no quick fix to trichotillomania, but with training, patience, and practice, you can reduce your hair pulling behavior. You can also talk to your doctor about a prescription numbing cream to use on your head, but some are not safe. There are new cooling hair products that are also safe to use on the scalp and eyebrows such as Prohibere and a hair product by Lush with menthol. This may be useful if one of your triggers is an “itchy” or "urge" to pull hair strange feeling in your hair. In a case study of a 16-year-old girl, it was found that temporary use of numbing cream in combination with psychotherapy was successful in eliminating hair pulling behaviors.

Improving Self-Acceptance and Self-Esteem

Be present in the moment. Hair pulling often results from a refusal to sit and be present with uncomfortable feelings or negative emotions. Use mindfulness techniques to help yourself become more accepting of these negative or uncomfortable emotions as a natural part of the human experience. They don’t necessarily need to be avoided. When the insistent urge to avoid discomfort abates, hair pulling will also decrease. To do a mindfulness exercise, sit in a quiet, comfortable spot. Take deep breaths. Breathe in for a count of four, hold for a count of four, and exhale for a count of four. As you continue to breathe, your mind will likely wander. Acknowledge these thoughts without judgment and let them go. Return your attention to your breath.

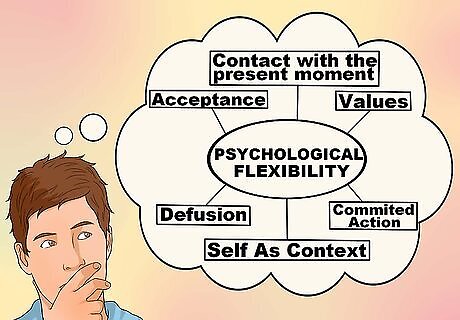

Build your self-esteem. Many individuals who are affected by this disorder also have low self-confidence or are low in self-esteem. In order to build self-esteem and self-acceptance, use Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT), a therapeutic approach. This approach can help an individual clarify her values and focus on her life goals. Building self-esteem is an important part of recovery. Remember, you are a wonderful and unique person. You are loved, and your life is precious. No matter what anyone else tells you, you should love yourself.

Replace negative thoughts with positive ones. Negative thoughts about yourself can deflate your self-esteem quickly and can make you feel like pulling your hair. Put-downs, fear of failure, and other negative thinking will keep you feeling as though you are not enough. Start changing these mental habits to begin to build yourself up and increase your confidence. Here are some example of how you can begin to change how you think about yourself: Say you have a thought such as, “I don’t have anything interesting to say, so I can see why people think I’m pathetic.” Catch unkind thoughts like this and make a conscious effort to change these thoughts by correcting yourself. Tell yourself: “Sometimes I don’t have much to say, and that is okay. I don’t have to keep others entertained or take on the entire responsibility for this conversation.” Replace critical thoughts with productive thoughts. For example, here is a critical thought: “There is no way I am meeting everyone for dinner. Last time I went, I was so embarrassed at my off-topic comment. I am so stupid.” Replace this with a productive thought: “I was so embarrassed at the last dinner, but I know that I make mistakes and that is okay. I am not stupid. I just made an honest mistake.” As you practice catching these thoughts and changing them, you will notice that your self-esteem will increase along with your confidence.

Write down your accomplishments and strengths. Another way to start accepting your emotions and improving self-esteem is to write down a list of your accomplishments and strengths. Refer to this often. If you’re having trouble coming up with a list, talk with a trusted friend or family member. This person can brainstorm some ideas with you. No accomplishment is too small for this list. Keep adding to the list.

Work on communicating assertively with others. Practicing better self-assertion techniques can help you to overcome situations in which you feel challenged by other people. For example: Learn to say no. If people are making requests of you that you don’t want to fulfill, assert your own needs and wants by saying no. Don’t be a people pleaser. Don’t do things just to secure someone else’s approval. Figure out what is really important to YOU. Ask for what you want. Use “I” statements. These types of statements help you convey responsibility for your own emotions and reactions. For example, instead of saying, “You never listen to me,” you can say, “I feel ignored when you are looking at your phone when we talk.”

Reducing Stress

Eliminate some of your stress sources. Many sufferers find that stress triggers the desire to pull hair. Do whatever you can do reduce stress in your life and learn how to manage the stress you do encounter with better coping techniques. Make a list of the things that stress you out. These can be large things, such as money or work, or they can be small things, like long lines at the grocery store. While you can’t avoid everything that causes you stress, you can minimize your exposure to some things.

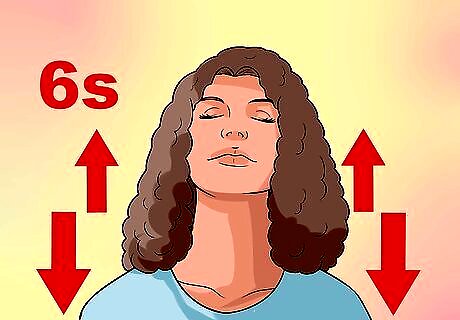

Relax your muscles through progressive muscle relaxation. You can reduce stress that you’re feeling by using progressive muscle relaxation. This type of relaxation reduces muscle tension, sending a signal your body to begin relaxing. By tensing and then releasing the tension in your muscles, you can slowing bring your body back to a calm state. Tighten your muscles for six seconds and then release for six seconds. Pay close attention to how each muscle is relaxing. Work from your head to your toes until you feel your body begin to relax.

Try meditation. Meditation can be helpful in reducing stress. A regular meditation regimen, even 10 minutes a day, can help clear your head and refocus your energy into a positive space. To meditate, find a quiet spot and sit or lie down. Begin breathing deeply, taking slow breaths. You might even try guided visualization, wherein you imagine a calm place such as a beach, a rippling creek, or a woodsy area.

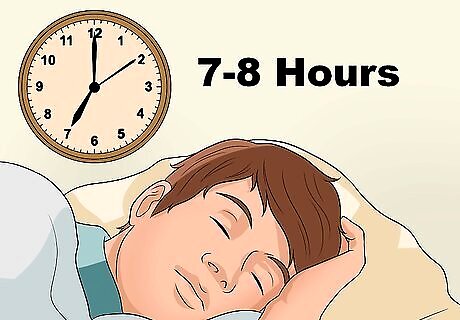

Get enough sleep. Ensure that you have a regular sleep pattern and that you're getting enough sleep every night. Aim for at least seven or eight hours of sleep every night. If you have trouble falling asleep, try listening to some soft music. Stop using any screen devices at least 15 minutes before you go to sleep.

Try exercise. Studies show that stress can be reduced considerably with a regular exercise regimen. Your body will increase its production of endorphins, which contribute to you feeling more positive. You don’t have to pound the pavement for an hour every day. You can participate in exercising that you enjoy. This might include yoga, martial arts, or other activities. Even gardening can give you an energy boost.

Finding Support

Talk to a trusted friend or family member. Find someone you trust and tell him or her about your trichotillomania. If you aren't able to talk about it out loud, write a letter or an e-mail. If you are afraid of talking about your struggle with this disease, at least talk to this person about your feelings. You might also tell your friends and family what your triggers are. This way, they can help remind you when you may be at risk of pulling your hair. They can also help you find an alternative behavior. Ask your friends and family to provide positive reinforcement when they see you successful engaging in a healthy alternative to hair pulling.

Talk to a mental health professional. A counselor or therapist can help you find ways of coping with your disorder. This person can also address any depression or other problems that may be contributing to your self-injury. If you visit one counselor or therapist and you feel you are not being helped, find another one. You are not chained to one doctor or counselor. It’s important to find someone you feel a connection with, and who you feel is helping you. The types of therapy that may be of benefit to you include behavioral therapy (especially habit-reversal training), psychotherapy, psychodynamic psychotherapy, hypnotherapy, cognitive-behavioral psychology, and possibly anti-depressant medication.

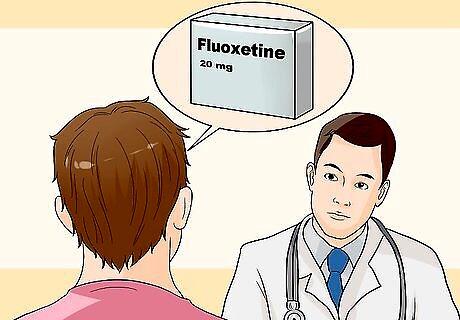

Ask your doctor about medication. Several medications have been shown to be effective in treating trichotillomania. Fluoxetine, aripiprazole, olanzapine, and risperidone are medications that have been used for treating cases of trichotillomania. These drugs help regulate the chemicals in the brain to reduce symptoms of anxiety, depression, and other emotions that can trigger hair pulling.

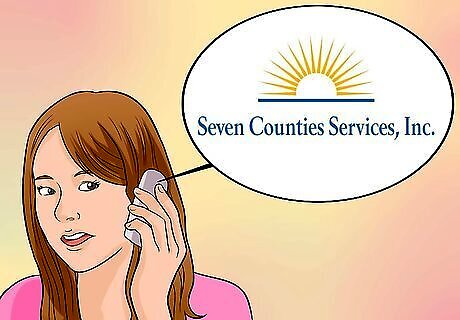

Consult a support group online or by phone. If you don’t have immediate access to counseling, there are other sources you can access. The Trichotillomania Learning Center has online support groups. Seven Counties Services, Inc. has a free Trichotillomania support hotline you can call. The number is 800-221-0446.

Diagnosing the Condition

Watch for certain actions or reactions that signal this disorder. Trichotillomania is officially classified as an impulse control disorder, along the lines of pyromania, kleptomania, and pathological gambling. If you suffer from trichotillomania, you may act or react in certain ways when hair-pulling. These might include: Chewing or eating pulled-out hair. Rubbing pulled-out hair across your lips or face. An increasing sense of tension immediately before pulling out the hair or when resisting the behavior. Pleasure, gratification, or relief when pulling out the hair. Catching yourself pulling hair without even noticing (this is called “automatic” or unintentional hair-pulling). Knowing that you’re pulling hair deliberately (this is called “focused” hair-pulling). Using tweezers or other tools to pull out hair.

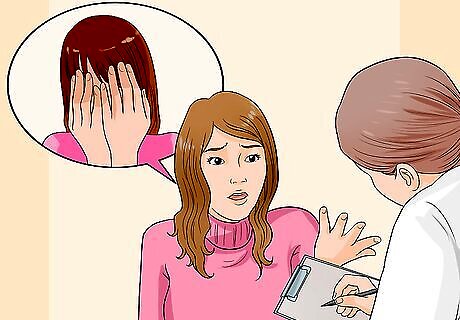

Recognize physical signs of this disorder. There are some tell-tale signs that a person may be suffering from trichotillomania. These include: Noticeable hair loss caused by recurrent pulling out of the hair. Patchy bald areas on the scalp or other areas of the body. Sparse or missing eyelashes or eyebrows. Infected hair follicles.

Observe if you have other compulsive body issues. Some hair pullers may find that they nail bite, thumb suck, head bang, and compulsively scratch or pick at their skin. Keep track of these types of behaviors over several days to see if they are habitual. Notice when you’re doing them and how often you’re doing them.

Evaluate if you have any other disorders. Determine if trichotillomania is the only disorder that's affecting you. Compulsive hair pullers may suffer from depression, obsessive-compulsive disorder, Tourette syndrome, bipolar disorder, phobias, personality disorders, and in some cases, exhibit suicidal tendencies. Visiting your doctor or mental health professional can be helpful in determining whether you have other disorders. However, it is complicated to say which disorder is causing which. Is the loss of hair causing the depression through the desire to isolate yourself from others and avoiding enjoyable activities because you feel deep shame? Often, successful recovery from Trichotillomania requires treatment for any co-existing disorders as well.

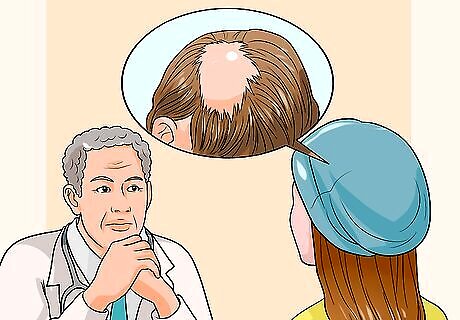

Talk to your doctor about hair loss disorders. Someone who believes that she suffers from Trichotillomania should be examined by a qualified doctor to rule out other hair follicle disorders. Some disorders include alopecia or tinea capitis, both of which can cause hair loss. When a doctor examines you, he will look for evidence of irregularly broken hairs, coiled hairs, and other hair abnormalities as signs of trichotillomania.

Recognize that trichotillomania is a disorder. The first thing to realize is that this can be treated; it is a disorder, not something due to willpower or lack thereof. The disorder arises as a result of genetic makeup, moods, and your background. When it kicks in, it's a condition in need of treating, not something to beat yourself up over. Brain scans have shown that people with trichotillomania have differences in their brain from persons not suffering from the disorder.

Understand that this disorder is a form of self-harm. Don't convince yourself that nothing is wrong; that your hair pulling is "normal.” Trichotillomania can be considered a form of self-harm, even though it isn't as talked about as other forms of self-injury. Like all forms of self-harm, trichotillomania can become an addictive behavior. With time, it becomes harder and harder to stop; that is why it's best to bring it under control as soon as possible.

Comments

0 comment