views

Determining Whether you Should File a Lawsuit

Resolve your issue without court intervention. Usually, people do not want to go to court, therefore, many people attempt to resolve any disputes they have with each other outside of court. Even if someone has wronged you, it may be better to try and work it out with them before filing a lawsuit. For example, if someone owes you money, you should ask the person for the money repeatedly before suing them for it and consider setting up a payment plan with them if they are having financial difficulty. If the payment plan works out, you will likely get the money that is owed to you must faster than if you sued for it. Lawsuits can be time-consuming and very expensive to get involved in, so you should try anything you can to work out your issue, and only file a lawsuit as a last resort.

Establish that you can file a lawsuit. Many companies, such as banks, insurance companies, and companies that provide services (cable/cell phone, etc.), include mandatory arbitration or mediation provisions in the contracts you sign with them. These provisions mandate that you cannot sue the companies because you instead must resolve any dispute through one of the out-of-court dispute resolution methods. Therefore, if you have signed a contract that has a mandatory Alternative Dispute Resolution clause, you will not be able to bring a lawsuit.

Verify that you have a valid legal claim. Before you file a lawsuit, you need to do some preliminary investigation to make sure that the law is on your side. If you do not have a valid legal claim, any lawsuit you bring will be dismissed by the court, and you will have wasted time and money. For example, if someone “promised” to give you $100 as a gift, you legally would not be able to sue them for the $100 if they didn’t give it to you, because the court will not force someone to give something for free. Similarly, if you are involved in a car accident with someone, but you were not injured and your car was not damaged, you will not have a valid claim because you do not have any damages, even if you know that the accident was not your fault.

Consider the strength of your evidence. Even if you do have a valid legal claim, you should assess the strength of your case before you file a lawsuit. To determine whether you have a strong case, consider the following: Whether you have evidence: you should consider whether you can prove what happened in a court of law. For example, if you need witnesses, were any present, and will they be able to testify at trial? If you need papers or documents to support your claim, do you have them, or can you get them before the trial? Whether your opponent has a convincing story: you should consider whether or not your opponent has a convincing story that conflicts with yours. If so, you should consider how you will convince the court that your story is better. Whether you can prove the legal elements: you need to know the elements or facts that you legally must prove to win your case. For example, in a “breach of contract” lawsuit, you must have enough evidence to prove that there was a valid contract. Without proving the existence of a contract, you cannot show that there was a “breach.” Whether you can collect money from your opponent: you need to know whether or not you will be able to collect a judgment if you win your lawsuit. It will not be worth the money and time it takes to bring a lawsuit if your opponent doesn’t have any money or assets, because you will not be able to collect anything, even if you win. However, if money is no object, you may want to consider a lawsuit anyway in order to get validation that your opponent was wrong. Who could be responsible: before filing a lawsuit, you should think of all of the possible parties that could be legally responsible for your harm. For example, if you were involved in an accident with a truck driver, you may consider suing not only the truck driver who struck you, but also his employer, if he was working at the time of the accident.

Figure out if your lawsuit is “timely.” Even if you have a great case, you will not be able to sue if you wait too long. You must file your lawsuit within the time that your state laws set as the “statute of limitations” for your type of claim. All states have their own time limits depending on the type of case. For example, one state may allow a plaintiff who wants to file a personal injury suit 1 year from the date of the injury, while another state may allow 4 years from the date of the injury. As a good rule of thumb, you will be okay if you file your lawsuit within a year from the date of the harm, no matter what type of claim you have or what state you live in.

Preparing to File

Hire an attorney. An experienced attorney can help you win your court case. Additionally, an attorney will be able to help you navigate the unfamiliar and sometimes complex court system. If you do want to hire an attorney, choose someone who has at least 3 years of experience, possibly more if your issue is extremely complex (for instance, a medical malpractice case). Most attorneys offer free consultations, so you can “interview” as many as you want until you find a good fit. Choose an attorney who has experience and strong knowledge of the law, and who you think that you would get along with and like working with. If the attorney makes you uncomfortable in any way or seems dismissive of your case or your situation, you should choose someone different to represent you. To find an attorney near you, consider talking to friends and family members who have used an attorney before. Find out who they hired, for what type of service, and if they would recommend the attorney. You can also find an attorney by checking online reviews. Many websites offer free reviews of businesses. Some places to look for lawyer reviews include:Avvo and Yahoo Local.

Decide whether you should file your case in state or federal court. The law establishes limits on which courts have “jurisdiction” (power) to hear and decide a case. You must file your lawsuit in a court that has jurisdiction over your case. Generally, you should file a case that deals with a state law in state court. The majority of cases, including personal injury cases, landlord-tenant cases, breach of contract, divorce, and probate matters, a state law claims. There are a few types of cases that should be filed in “federal court” instead of state court. If your case is based on a federal law, you can sue in federal court. A few examples of cases under federal law include suing a police officer under the federal civil rights statute (called a 1983 case) or suing because a government organization has unlawfully discriminated against you.

Decide where you should file your case. Usually, you should file your state court case in the state where the actions occurred. For example, if you are suing for injuries sustained at your workplace in Delaware, you would want to sue in Delaware. Once you figure out which state to sue in, you also need to figure out which court in that state is the correct one to sue in. Most states have different “levels” of courts that plaintiffs can file in depending on how much money they are asking for. Typically, states will have the following courts (which may have different names) to choose from: Small claims court: small claims courts will usually hear claims that involve a certain amount of money - usually up to $2,500 - $5,000. Courts for medium-sized claims, often called “district courts:” usually, the district court will hear cases that involve claims of up to $25,000, Courts for any cases with larger claims, often called “circuit courts:” there is usually a court that will hear claims that are about $25,000, and also certain specialized statutory claims that specify in the law which court will hear them. If you file your claim in federal court, you will always file in the “district court.”

Filing Your Lawsuit

Prepare your complaint. To sue someone, you must prepare a document called a complaint that you will file with the court. The complaint includes the grounds or cause of action for your lawsuit. If you have a lawyer, she will draft and file your complaint. If you are filing on your own, you can use a legal book or CD of legal forms to write out your complaint. You can also copy the style of an existing complaint you find on the Internet or from another lawsuit that was filed in your jurisdiction. For more information on how to write and format a pleading, visit WikiHow’s Guide on How to Format a Legal Pleading.

File your complaint at the courthouse. After your complaint is completed, you should take two copies to the court where you are filing your suit. You will give your complaint, along with a “filing fee” to the court clerk. The clerk can also answer questions that you may have about the process. In some states, you must sign your complaint in the presence of the clerk or get it notarized. Check your state court’s website to see if this applies to you. You do not need to make an appointment to file your complaint. However, you should make sure that you go to file the complaint during the regular business hours of the court.

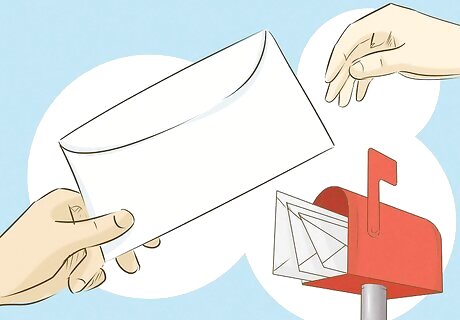

Serve the defendant. The court cannot locate a party for you. You must have a current physical address, such as a home or work address, in order to sue someone. This is because the rules of procedure require that you provide a defendant notice of the lawsuit and give him or her an opportunity to respond. Most states allow you to serve a defendant by mail, or by personal service, through the County Sheriff or a process server. Some things to consider when deciding where and how to serve the defendant: Your state may require personal service of the initial Complaint: if personal service is required, you will need to have the County Sheriff or a process server serve the defendant. When serving via the County Sheriff, the Clerk’s Office and/or the Court will take care of making the arrangements. Personal service may or may not be offered by your County Sheriff’s Department. If the Sheriff offers personal service, there may be a fee. Call the County Clerk or the Sheriff’s Office to determine if process service is offered, and what the fee is. Your state may require a signature from an appropriate person when serving the defendant. Check with your state’s Rules of Procedure for service or with an attorney in order to determine if the process server may leave a copy of the Complaint at the defendant’s home or work, or if a signature is required. If allowed for the initial Complaint and Summons, service by mail is usually sufficient and reliable, and is usually less expensive. However, if you have any reason to believe the Defendant may attempt to hide from service, it may be best to pay for personal service.

Gather facts about your case through discovery. After you file your lawsuit, you will need to gather the evidence you will use to prove your claim. Typically, you can request evidence from the other party (called “discovery”). Discovery allows the parties to get investigatory information on the case from the opposing party. Discovery includes: Requesting documents from your adversary, Sending “interrogatories,” (or written questions), to your adversary that must be answered under oath in writing, “Deposing” your adversary by asking oral questions that must be answered in person, under oath (this is a little bit like an interview), and Writing and sending the opposing party “requests for admission,” which are essentially requests that the opposing party admit under oath that certain facts are true.

Conduct “informal investigation.” In addition to formal discovery, you can gather your own evidence related to your case. Informal investigation can include the following: interviewing witnesses, getting documents from someone other than your opponent, taking pictures (either of the scene of the accident, of the damaged property, etc.), and finding out as much as you can about your adversary without speaking to them, or contacting your adversary without your attorney’s help to ask questions. If possible, try to investigate your case using “informal discovery” type practices as opposed to formal discovery.Formal discovery can be extremely expensive and also very complex, so sometimes it's better to investigate on your own, especially if you don’t have a huge amount of money at stake.

Considering Your Options Before Going to Trial

File a Motion for Summary Judgment. Depending on the facts of your particular case, you may file a “motion for summary judgment.” A motion for summary judgment is a pleading that can be filed by either party, assuming that the party believes that depositions and affidavits demonstrate that there are “no genuine issues of material fact” that a jury needs to consider for a verdict to be rendered. Essentially, this type of motion argues that there are no issues of the facts, so the case can be decided by the judge on the basis of the law only. Discuss the possibility of a motion for summary judgment with your attorney. If you do not have an attorney and your opponent files a motion for summary judgment, you should argue in response that there are facts that are disputed, and those facts are what will determine the outcome of the case.

Settle your case before trial. Even after filing a lawsuit, you can still try to work things out with your opponent. In fact, most cases actually “settle,” or a worked out, before trial. Settling with the opposing party is a good idea for many reasons including: Settling will save you time: trials are often long and drawn out, therefore, settling now means that as a plaintiff, you will receive money sooner rather than later. Settling is easier than trial: as someone representing yourself, going all the way through the trial can be stressful due to the complex and unfamiliar nature of the legal system, settling will save you from having to navigate all the way through a trial on your own. Settling insures you agree to the outcome of the case: if you end up going to trial, you really have no idea how the judge or jury will decide your case. Additionally, sometimes, even if you should win, you don’t (or you don’t win nearly as much money as you are entitled to). Because settling a case means that the case doesn’t have to go all the way through the legal system, judges often encourage parties to settle cases as well, and sometimes provides help to parties who want to try and work it out. Ask the clerk in the court where you filed your lawsuit whether there are any resources available to parties who want to settle.

Go to mediation. Mediation is an “alternative dispute resolution” technique where a third party “neutral mediator” (that is, someone who is not on your side, or your opponent’s side), yourself and your opponent discuss the case and try to come to an agreement on a settlement. The mediator is there to help the parties discuss the issues without getting angry or frustrated with each other. Many states offer low-cost programs that supply mediators for various types of cases, including landlord-tenant disputes, divorce cases, and disputes between neighbors. To prepare for a mediation session, do the following: Think about what outcomes would be acceptable to you: think about what you want from your opponent, and don’t limit yourself to asking for money. For example, many people want an apology from the person who they think wronged them. Prepare to show the mediator the evidence that supports your claim. This will allow the mediator to get an idea of whose side of the case is “better,” and, even though the mediator cannot force you or your opponent to accept a settlement, they may be able to discuss the chances each party would have at trial. Remember that the goal of mediation is come up with a settlement that works for both parties. Don’t go into mediation with a mindset that you have to “win” or “punish” your opponent. Instead, you should be prepared to work collaboratively with the mediator and your opponent to come up with a creative solution to your issues.

Arbitrate your dispute. In addition to mediation, you may consider participating in “arbitration” to resolve your lawsuit. Arbitration is similar to a trial, but is more informal. In an arbitration proceeding, you and your opponent present oral testimony, documents, and other evidence to a neutral third party (the arbitrator) who then makes a decision based on both sides' case, usually called an “award.” Unlike mediation, an arbitrator’s award is binding on the parties, so whatever the arbitrator decides goes. Arbitrators are trained and are almost always retired judges or lawyers. You should prepare for arbitration the same way that you would prepare for trial (see below for more information).

Going to Trial

Understand who will decide your case. If you do proceed to trial, your case will either be decided by a judge or a jury. Usually, the parties decide whether to have the case decided by a judge or jury. In some cases, you may want to ask for a judge and not request a jury.If you are representing yourself, a trial before a judge is likely to be more informal, and you will not have to worry about the jury’s impression of you in the courtroom. You should ask for a jury if your case has “emotional appeal” and you think the jury may be sympathetic to your cause. However, keep in mind that this can backfire if someone on the jury doesn’t like you. Keep in mind that the trial will have all of the same “parts,” regardless of whether you are in front of a judge or a jury.

Give an opening statement. The “opening statement” is a type of speech given at the start of the trial. It is your first opportunity to introduce yourself and your case. If you filed the lawsuit (and therefore are the plaintiff), you will give your opening statement first, followed by the defendant. In your opening statement, you should give an overview of what your case is about and what your evidence will prove. You should begin proving your case by telling the jury what evidence is in your favor and what happened to you. Keep in mind that you cannot state your own opinions in an opening statement, and if you do so you could be reprimanded by the judge.

Call and examine your witnesses. During the presentation of the case, you will call your own witnesses, and “examine” them (this is called direct examination). You will also have the opportunity to ask questions of your opponent’s witnesses (this is called cross-examination). To prepare for calling and examining your witnesses, make sure that they all agree to be present at the trial. For direct examination, you should prepare a notebook with an outline of what you want to ask the witnesses. Ask questions that will encourage the witnesses to talk, instead of “yes” and “no” questions. To get comfortable with questioning witnesses, you can meet with them to practice beforehand. For cross-examination, realize that you probably won’t get that much useful information, and limit or completely forgo examining the opposing witnesses. Only cross-examine the opposing witnesses if you can get evidence from them that supports your version of events or discredits their trustworthiness as a witness. Always be kind and polite to any witnesses, even during cross-examination. Arguing with or badgering a witness (even an opposing witness) looks bad to the jury, and could get you in trouble with the judge.

Deliver your closing argument. A closing argument is delivered at the end of a trial, after all of the evidence has been presented and all witnesses have been called. A closing argument is the last chance you will have to address the judge or the jury. Closing arguments are usually between 10 and 20 minutes, but, if the case is extremely complicated, they can be much longer, in some cases up to one hour. Unlike an opening statement, which can be written well in advance of the trial, a closing argument will be based on the events of the trial, so to prepare an effective closing argument, make sure that you take notes throughout the trial. To see in-depth information about preparing a closing argument, visit wikiHow’s guide on writing a closing argument.

Decide Whether to Appeal. Even after the trial has ended, the losing party can appeal the loss to a higher court. An appeal is a request to a higher court to review and overturn the decision of a lower court. In federal court, appeals are heard by the United States Court of Appeals. In state court systems, the appeals courts go by various names. If you think you might want to appeal the decision in your case, make sure you understand the following: How appeals are decided: generally, the courts of appeal do not want to tell the trial judge that he made the wrong decision, or “overrule” that decision. Therefore, an appeals court will usually only overturn the decision of a lower court if the lower court made a significant error of law.What a “significant error of law” is will be completely different depending on each particular case. What evidence you can present: The courts of appeals do not look at any new evidence that may have been discovered after the case was decided (either by the judge or the jury). Instead, the court will look at the documents from the case, a “brief” by both parties discussing why each one believes that they have the correct view, and in some cases, will listen to both parties argue your case in front of the court (this is referred to as “oral argument). The consequences of an unsuccessful appeal: if a party unsuccessfully appeals the court’s order, the higher court will “affirm” the lower court’s ruling (or the jury’s), and the current judgment will stand. For more information on appealing a court order, visit WikiHow’s guide on Appealing a Court Order.

Comments

0 comment