views

Putting Your Bow Together

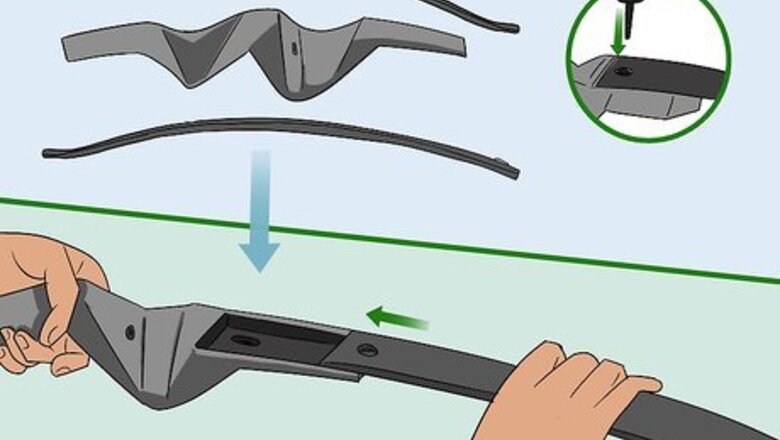

Screw in the limb bolts for a takedown recurve. Slide the limbs into the slots on the riser. Use the bolts provided to screw in the limbs. Some bow's limbs can be done by hand, but others will require a hex wrench. Most bows will require quite a long time to screw in the bolts, so remain patient. If you are having trouble, try screwing the bolt all the way into the limb and fitting the limb into the riser slot afterward.

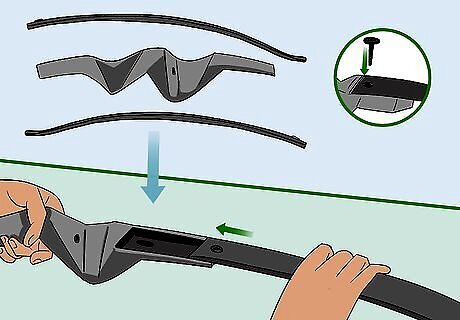

Know how to string your bow. Purchase a stringer tool to do this safely and avoid damaging your limbs. Stringing your bow with the step-through or push-pull methods can twist the limbs and render any warranty you have void. The larger string loop goes on the top limb and the smaller loop will go on the bottom limb. Place your string on the bottom limb and pull it up as far as you can to the top limb. Put one pocket of your stringer on the bottom limb-tip and place the other rubber block/pouch just below the top string loop. Step on the stringer (not the string) and pull the bow up, sliding the top loop onto its place as you do. Give it a pluck when you're finished, to make sure the string is seated properly on the limb tips. Make sure you're not stringing the bow backwards. A recurve bow's limbs bend away from the archer. Many people believe all bows look like a longbow and, thus, string them backwards. If you are having trouble, try stepping on the stringer with two feet or tying knots in it, to shorten the length of the stringer. If the limb tips are too sharp and cut into the protective serving at the end of the string, smooth it with sandpaper. It's also best to unstring your bow after you're done. This isn't necessary since most bows are made of modern materials that prevent the limb from setting, but it's good to have the peace of mind knowing that nobody will be able to pick up your bow and dry-fire it.

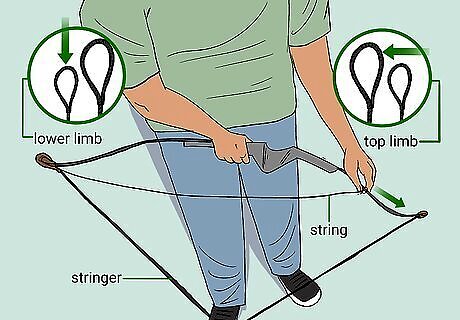

Make sure you have the right bow. Test your eye dominance. If you are right eye dominant, hold the bow with your left hand and draw the string with your right (the arrow shelf should be on the left of the riser). If you're left eye dominant, hold the bow with your right hand and draw the string with your left (the arrow shelf should be on the right of the riser). However, if you are cross dominant (opposite hand and eye dominance) you will need to decide which one to use. Some people will wear an eye patch over their dominant eye and use their dominant hand. Others will go with their dominant eye and non-dominant hand to hold the bow.

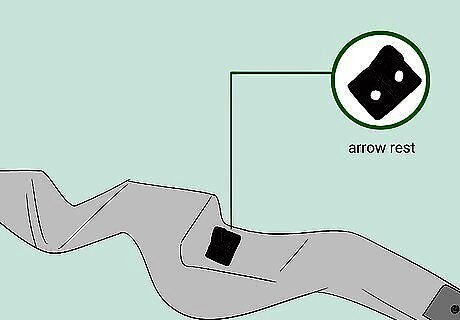

Attach an arrow rest or shelf pad. The plastic stick-on rests are usually the best quality, even though they're dirt cheap (from $1 to $6). Both Olympic and barebow archers use them for consistent placement of the arrow. If you want a traditional look, go with a fur shelf pad to stick on the bottom of your arrow shelf. Both prevent the arrow from scraping the shelf which would affect your accuracy and are usually stuck on with an adhesive pad. You can shoot both vanes and feathers off of a plastic rest, but you should only shoot feathers off a fur shelf. Vanes tend to deflect off the surfaces changing the arrow's flight a little. Don't get a magnetic rest, as it is more expensive and will move around. Wipe the riser with an alcohol wipe prior to attaching the rest/pad. This gets rid of dirt/grime/remnants from the previous adhesive that could prevent it from sticking properly.

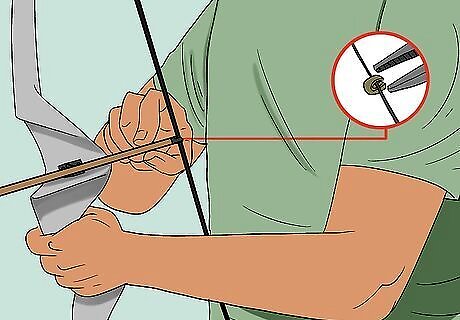

Add or tie on nocking points. These are usually small metal pieces that prevent the arrow from sliding upward on the string and let you know where to nock it. Use pliers to attach them approximately ⁄2 inch (1.3 cm) above your shelf/plastic rest, although you might change this when tuning your bow. You can use an arrow to know where to place the nocking points or buy a bow square. Many archers also tie their own nocking points using thread or floss. Run the thread/floss through some type of glue before tying. Tie one knot on each side of the string, alternating until you feel it is large enough. Singe the ends using a lighter/match to melt the glue and make the nocking point last longer. You can only use one nocking point and always place your arrows below it, or use two and place your arrow in between them. Make sure there's enough space between them if you decide to use two, so the arrow doesn't have trouble coming off the string.

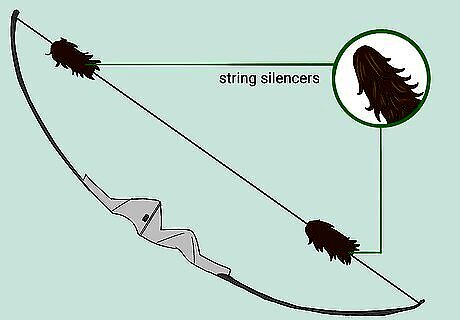

Put on string silencers or dampeners. Some bows tend to be louder than others when they slap the upper limbs during each shot. You should attach these if you plan on hunting, to avoid frightening your game. Dampeners reduce vibration in your bow and go on the limbs. You can make your own string silencers using yarn on the string or tying some around the limbs where the string will strike them. They may not, however, look as good.

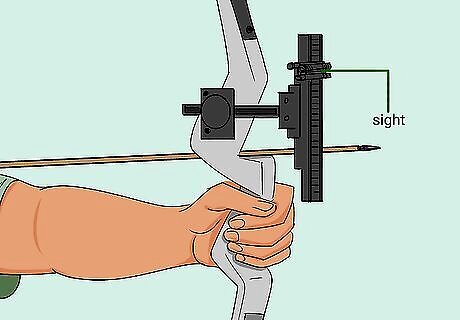

Attach a sight. They simply act as a point of reference and most don't offer magnification. Recurve sights usually consist of two metal bars that have markings on them or a hole with multiple pins for shooting different distances. Place your bow on its side and align your sight with the hole in the riser. Install the screws using either a screwdriver or Allen wrench, depending on what you're provided with. Sights have different methods of changing its elevation. Some use micro-adjustable wheels while others require loosening screws by hand. Get a quality one to start out with. Cheap sights (beginning at $10-30) come loose and are difficult to adjust, but a Shibuya sight (around $200-$300) will have finer and easier adjustments. You won't use a sight if you plan on shooting barebow/traditional recurve.

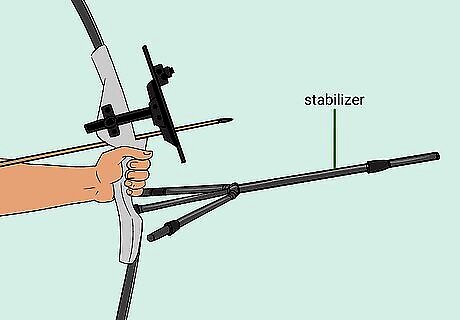

Screw in a stabilizer. This is essentially a weight to help keep your bow balanced and reduce vibration. You can screw one into a hole on the front of your riser on most bows. The length of the one you buy varies; if you are going to be hunting, it would be preferable to have a short 6-inch stabilizer. If you're an Olympic archer shooting distances of 70 meters, you'll want a steadier 30-inch stabilizer. This hole can also fit a bowfishing reel if you wish to do that. You don't need a stabilizer for backyard shooting or hunting. However, competitive archers use them to shoot better groupings and reduce bow torque.

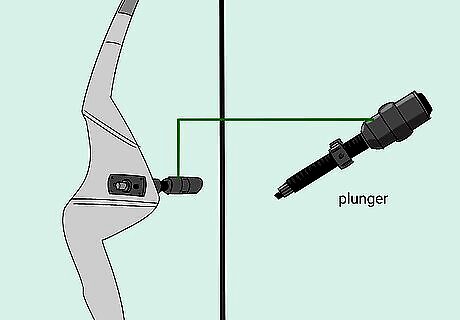

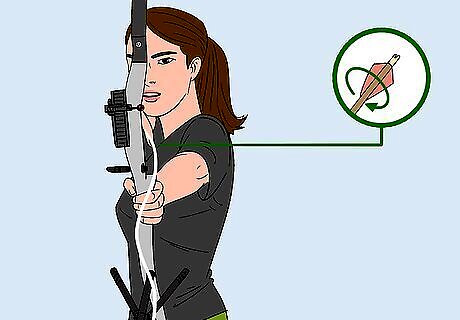

Put on a plunger. A plunger acts as a shock-absorber, stopping the arrow from moving inward and pushes it slightly away from the riser. Screw it into a hole on the side of your riser. Make sure it's the one that matches the hole in your arrow rest so that the plunger will go through. Tighten it so that it won't rattle while you're shooting. Many arrow rests come with a small flap that acts as a pseudo-plunger. You can cut this off if you are planning to use a plunger with it. You will need to properly tune it so that the plunger doesn't cause the arrow to deflect or cause clearing problems. Plungers get expensive, and it's fine to get a cheap one to start off. Better to have one than to have none.

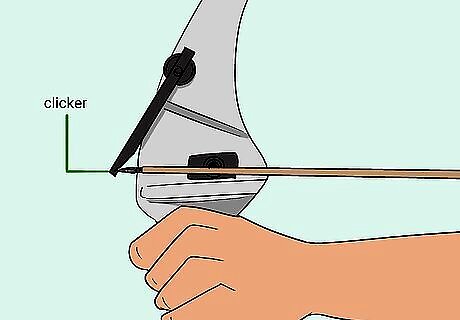

Get a clicker. It is a strip of metal (aluminum or carbon) that juts out from the riser and goes over the arrow. Once you've reached the end of your draw, it'll click, letting you know to release. They either screw into a hole on the riser or are stuck on with an adhesive pad and can be adjusted to your draw length/arrow length. You will need a correct draw and anchor for the clicker to help rather than harm you. A clicker is typically used by more advanced Olympic archers who have fixed their draw length (tends to change when beginning slightly). When using a clicker, it is necessary to use arrows with the right length and have all of them at the same length. With practice, the sound of the clicker is the mental trigger and you will instinctively release as soon as you hear it.

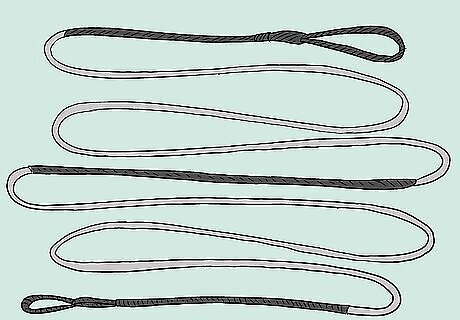

Make sure you have the right string length and material. Older recurves that are made mostly of wood should only have Dacron strings. Fast flight (any bowstring with modern materials), Flemish twist strings, or endless loop can be used on newer recurves to get about 5% more FPS (feet per second) on your arrows. Different strings have many different components and it's up to you which string you want to use. Fast flight and Flemish strings or endless loop can be used on newer recurves to get about 5% more FPS (feet per second) on your arrows. Flemish twist strings are also quieter than Dacron ones. You can make your own strings by buying a string-making jig and learning how preferably getting taught by someone at your club. Your string should have an AMO length of the length of your bow. The actual length of the string should be about 4 inches (10 cm) shorter than the bow. Be careful about whether the seller is measuring the string using AMO length or the actual string length. Dacron strings tend to stretch as you use them more than Fast Flight or Flemish varieties.

Wax the bowstring when necessary. Buy bowstring wax to keep your bowstring functional for longer. Before waxing, rub the string with your fingers to warm it up and melt the wax. Coat the string with a thick layer of wax and rub it in to get all the strands covered. Clear off the excess by running floss down your string afterward. Do not wax your servings, which are the layers of extra protection over some parts of the string. Some people do this after every practice, but you only need to apply wax when your string starts to feel dry (don't wait for it to dry out completely).

Tuning Your Bow

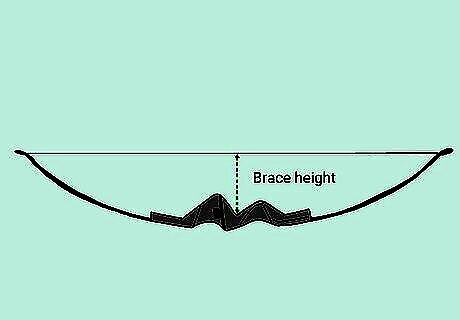

Establish your brace height. Most manufacturers recommend a brace height anywhere in the range of 7 inches (18 cm) to 9.5 inches (24 cm). You can change your brace height by adding (increases brace height) or removing (reduces brace height) twists in your string. The perfect brace height for you is where the bow is the quietest and results in the least vibration. String your bow without any twists, take note of the brace height, and shoot a few arrows. Have someone observing you if possible to get hear how much noise the bow makes when you shoot. Adjust the brace height by adding 3 twists. Each time, measure the brace height and shoot some arrows until you get to the quietest point. Mark that amount of twists down for reference; some people will write it on the limbs of their bow. The ideal brace height varies based on draw weight, bow, string material, and your arrows. Don't take another person's recommendation; the perfect setting can even vary with two of the same bow.

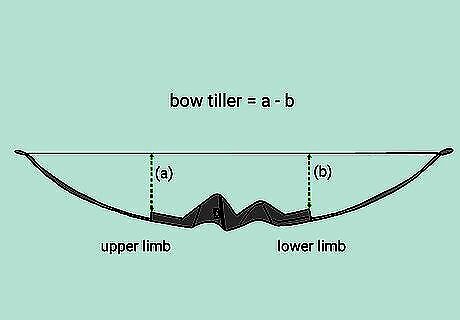

Check your bow's tiller. This is the gap between the string and the upper limb compared to the gap between the string and the lower limb. Recurves are meant to be shot with a positive tiller which means the gap between the bottom limb and the string is smaller ⁄4–⁄8 inch (0.64–0.32 cm) than the other one. This means that the bottom limb is heavier than the top limb On a one-piece recurve, look for where the limbs begin to curve and measure to the string. On a 3-piece takedown, measure from where the limbs meet the riser. The reason for a positive tiller is because when you nock an arrow, it isn't in the exact middle of the bow (in fact, the grip is). This imparts an uneven pressure on the limbs, but with a positive tiller, the limbs will both return to their places at the same time after you shoot. Without the right tiller, your bow will have excessive vibration, shoot slightly off-balance, and be pulled off because one limb is under too much tension. The effects of an improper tiller can be reduced by using a stabilizer. You can also move your nocking point up or down If you are shooting a modern recurve with adjustable tiller bolts, be sure to turn each of them the same distance when you're adjusting; eg. 1 full turn on the top one and 1 full turn on the bottom one.

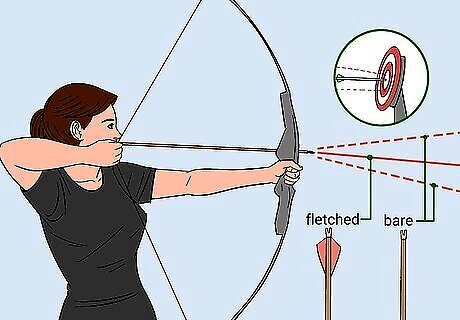

Fix porpoising in your arrows. This is when the arrow's flight fluctuates up and down towards the target and it means that your nocking point is not in the most optimal position. Conduct a bare shaft test to diagnose this problem. Place a target 20 yards (18 m) away and shoot 2-3 fletched arrows at a particular spot. You can move it closer if you aren't accurate enough yet. Standing from the same position and aiming at the same location, shoot 2-3 unfletched arrows (bare shafts). If the bare shafts landed higher than the fletched shafts, your nocking point is installed too low on the string. Try moving it upwards ⁄8 inch (0.32 cm) at a time and conducting the bare shaft test each time. If the bare shafts landed lower than the fletched shafts, your nocking point is installed too high on the string. Move it down ⁄8 inch (0.32 cm) at a time. Once both sets of arrows land at the same vertical height on the target, your nocking point is at the best spot.

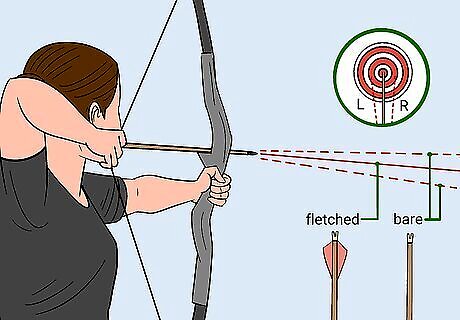

Check for fishtailing in your arrows. This is similar to porpoising, but the arrow turns left and right and is caused by an improper spine on your arrows. As before, place a target 20 yards (18 m) away and shoot 2-3 fletched arrows and then 2-3 unfletched (bare shaft) arrows. Make sure you're standing in the same spot and aiming for the same place on the target. If the bare shafts land noticeably left of your fletched arrows, your arrows have too stiff of a spine. There are a few ways to fix this problem. Reduce the tension on your plunger if you have one. Use heavier arrow points than you are using. If you have 125-grain points, switch them out for 150-grain points. Increase the brace height by adding a few twists when stringing your bow. If the above options don't help, you will need to buy new arrow shafts at a lower spine. If the bare shafts land noticeably right of your fletched arrows, your arrows have too weak of a spine. Try doing the reverse of the solutions above. Increase the tension on your plunger. Use lighter arrow points; eg. switching from 125-grain points to 100-grain points. Decrease your brace height (by 1/8 in. each time) by removing twists when you are stringing the bow. If these don't work, you'll need to get new arrow shafts with more spine than the ones you have right now. Try consulting the manufacturer's chart if you didn't before.

Get proper clearance on your arrows. Because of something called the archer's paradox, the fletchings/vanes on an arrow don't making direct contact with the bow when you shoot. However, if the shafts don't clear properly, it will reduce your accuracy and increase your grouping size. Find a powdery substance that will be disturbed by your arrow, yet will also stick to the riser. Apply a layer of powder to the arrow shaft in between the nock and the fletchings, the fletchings themselves, 2 inches (5.1 cm) of the arrow shaft below the fletchings, and your arrow rest. Shoot a fletched arrow while being careful to avoid disturbing the layer of the substance you applied. Release the arrow at a target that will stop it before the fletchings penetrate. Examine all the spots where the powder has been disturbed. The most common problem will be the fletchings not clearing the rest properly. Rotate your nocks very slightly and continue the test after each adjustment until the fletchings no longer leave marks. Try putting on smaller fletchings such as parabolic ones (curved). Make sure you've conducted the bare shaft test and corrected any porpoising in your arrows before conducting the arrow clearance tests.

Comments

0 comment