views

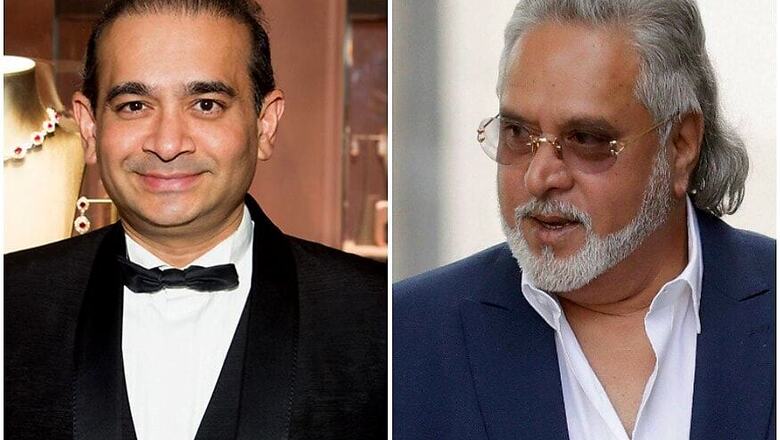

London: Following straight on from the Vijay Mallya case, overlapping issues and common questions will arise inevitably in the extradition hearings for Nirav Modi now underway at the Westminster Magistrates' Court in London. But an odd echo has arisen over identical sections in witness statements presented by the Indian government.

Clare Montgomery, appearing for Nirav Modi after representing Vijay Mallya earlier, pointed out certain examples to the court.

Statements from Supriya Sakhare and Jasmine Makwana, both cited as government witnesses on the critical point whether the Letters of Undertaking (LOUs) from the Punjab National Bank were issued irregularly, contain lengthy identical passages which replicate grammatical mistakes, Montgomery told the court.

She brought up the expression “Rs 99 Lakhs each were got prepared” that’s common to statements from both witnesses. Another expression in common between both statements, that she said also failed properly to attribute actions, was: “I asked Shri Joshi who was the caller.” This fails, she said, to clarify whether it was Ms Sakhare or Ms Makwana who did the asking.

Such repetition, Montgomery said, strongly suggests drafting and “copy-pasting” by the investigating agency rather than an accurate recording of evidence by witnesses. It “strongly suggests the statements were drafted by the CBI and ED on the basis of their own views rather than recording the words of the witnesses themselves”.

The dispute goes back to statements taken and presented under section 161 rather than section 164 of India’s Criminal Procedure Code (CrPC). Section 161 authorises a police officer to orally question anyone acquainted with a case and to “make a separate and true record of the statement of each such person whose statement he records”.

Section 164 gives the authority to record a statement to a magistrate who must “explain to the person making it that he is not bound to make a confession and that, if he does so, it may be used as evidence against him”. The magistrate must be satisfied that the statement is being made voluntarily. He must then (under related section 281) make a memorandum of the summary and sign it. The CrPC demands that “the whole of such examination, including every question put to him and every answer given by him, shall be recorded in full” and “the record shall be shown or read to the accused”.

Defence for Nirav Modi argues now that statements under section 161 should be inadmissible. These statements, it is argued, offer no information about the circumstances in which they were taken, and are not signed by the witness. Many of the statements that defence for Nirav Modi contests, and that include repetitions, have been recorded under section 161.

The objection from Nirav Modi’s team is to more than repetition. “A large number of statements contain information which does not appear to derive from the witness’s own knowledge, but from information put to them by the investigating agency,” Montgomery said. “Second, and relatedly, significant evidence is given which is hearsay, and therefore not evidence which the witness can admissibly give.”

Helen Malcolm appearing for the Crown Prosecution Service, the official British prosecution agency arguing the case on behalf of the Indian government, told the court that it is accepted that the affidavits of the investigating officers cannot amount to admissible evidence of matters the officers did not witness. “It is not, and has never been, suggested that the Government of India response documents are admissible evidence in relation to the court’s consideration of prima facie case. However, that does not mean they are of no relevance to the court’s prima facie case consideration. Observations made within them in relation to admissible evidence can be taken into account.”

Much the same issue was raised by Montgomery in the course of the hearings in the Mallya case. Then too a number of statements from witnesses declared to be independent included large sections that repeated one another verbatim. Chief Judicial Magistrate Emma Arbuthnot who heard the Mallya case made it clear that she was not relying on such submissions as evidence. But, she ruled, “there is no reason why the points they (the witnesses) made on the documents could not be taken into account as informed explanations of or commentary on the documents, rather than as evidence of relevant events”. The statements were accepted as illustration, not evidence.

Malcolm told the court that the objections being raised now were among issues “raised and dismissed” in the Mallya case. They effectively stood dismissed in appeal in the High Court as well. Verbatim repetition in witness statements in the Mallya case did not come in the way of the Indian government winning that case in both the district court and the High Court, which on April 20 confirmed the extradition order passed by the magistrate’s court earlier. Before the Mallya case too, objections over admissibility of statements under section 161 of CrPC have been “consistently rejected by UK extradition courts”, Malcolm said.

These arguments will now be for magistrate Samuel Goozee to consider when the hearings resume on September 7 for five days. That is when the court is due to consider additional charges presented relating to "causing the disappearance of evidence" and “criminal intimidation to cause death”. Those issues appear a great deal more serious than that of language repeated across affidavits.

The defence argument is of course not about statements getting their grammar wrong, but about getting the grammar wrong in the same way, and what that suggests. A simple explanation for this was offered to Magistrate Arbuthnot by Mark Summers who appeared for the Indian government in the Mallya case: that it simply was the practice for a junior police investigating officer to hear oral statements and to then record them in his or her own language. And if witnesses appeared to be saying much the same thing, this officer would not feel burdened by a need to write the statements down in different language all over again.

In court these statements could be illustration, not evidence. In police stations these are illustrative of another reality.

Comments

0 comment