views

MP and writer Shashi Tharoor’s oft expressed views on the reparations owed to India by the former British Empire stoke the patriotism of every Indian who hears and or watches them, and rightly so. And while we do agree with everything the esteemed gentleman so eloquently states, we have a small addendum to make, to wit, Anglo-Indian cuisine. While this particular facet of the crown jewel that was India was also developed as an Indian means to a British end, we suggest that it at least added value to the country instead of detracted from it. But why take our word for it?

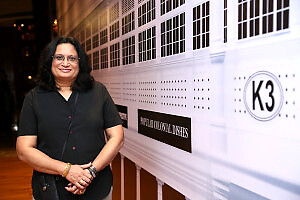

Bridget White Kumar is the preeminent authority of the syncretic cuisine that was crafted over the entirety of the British Raj, and perhaps beyond. Having dusted off and uncovered a myriad old recipes and written a number of cookbooks, White Kumar has also curated a number of culinary lessons and experiences for leading hotels of the country. Currently stationed at the JW Marriot Aerocity in New Delhi for a hatke (pardon our Hindi) Independence Day festival, we caught up with the food historian and writer to delve back through the ages and pages of culinary yore.

Delving is a subject White Kumar grew up with as the the fourth generation of a British, and subsequently Anglo-Indian, family that worked and lived at the Kolar Gold Fields, located outside present-day Bengaluru. The gold mining works and community can said to be established when John Warren, a British surveyor, set up a camp in the region in 1802. Interestingly, one of the earliest recipe tomes found by White Kumar is dated around the same time, attributed to an unknown author but subsequently published by Higginbotham’s, another relic of the Raj. As she attempted to recreate the ages-old recipes in a modern day kitchen and calculate what a ‘two paisa of coriander’ and ‘five paisa of red chilies’ would amount to today, she discovered a spark to fuel a new fire, as it were. It probably helped that she had been a banker.

Indeed, this culinary career was White Kumar’s third, following stints as a teacher and the aforementioned banker. She also found the time to dismay the good people of KGF when she married a Hindu South Indian; they came around after a month, and we imagine the prospect of Chettinad food may have helped in this. In any case, following her early retirement from the banking center and subsequent discovery of dusty old recipe books, including an Indian cookery book printed on the storied Gutenburg press, sparked as we said an interest that would lead to the publication of White Kumar’s first book, printed by her local church.

While the first book was meant for as a resource for White Kumar’s daughter as the latter left for college in the UK, further digging up of recipes as well as anecdotes had her, er, digging in more and more. For instance, the Dak Bungalow Chicken Curry, a mainstay of any Colonial-era menu, developed at the dak, or postal, bungalows that dotted the various highways that bisected the country. Each bungalow was maintained by a man-of-all-work and his family, who used to throw together whatever was locally and seasonally available, along with one of the chickens they reared, whenever a mail carriage came rattling in. As several generations of the servitors, and the many, many more generations of their fowl passed, the birds began to identify the rumbling of the carriage wheels with imminent death and descend into a panicked cacophony, or cock-aphony if you prefer. Hence, the other name for this storied dish is the ‘Sudden Death’ curry.

Then of course is the Railway Mutton Curry, referring to the curried mutton served on the ‘Blue Trains’ that began at Victoria Terminus in Mumbai and chugged all the way to Calcutta, via Nagpur. Given that steam was the pinnacle of modern technology at the time and refrigeration was non-existent, no food was prepared or cooked on the train (the wagons of the time having been constructed almost entirely of wood may also have something to do with this logistical anomaly). Instead, as the railways presumably didn’t want their passengers to starve over the course of the journey, food was picked up at various stations along the route. And since there were no fridges or freezers (or electricity), the curries had tamarind-water or vinegar added to them, to prevent spoilage. Rather amazingly, this enabled them to stay preserved over two or three days, with the acidic addition also imparting the curries with their characteristic sour taste.

These two curries are among a whole menu the kitchens at JW Marriot are turning out under the aegis of Executive Chef Vivek Bhatt and White Kumar. The curries are quite watery (a la the British palate) and meant to be mopped up with assorted Western breads, rather than our local rotis, an interesting variation of this particular style of cuisine. There’s no dearth of flavor here, however, and our visit had us finish our meal on crockery as spotless as before we festooned them with curries, chops and other provender. History has never gone down so easy.

Comments

0 comment