views

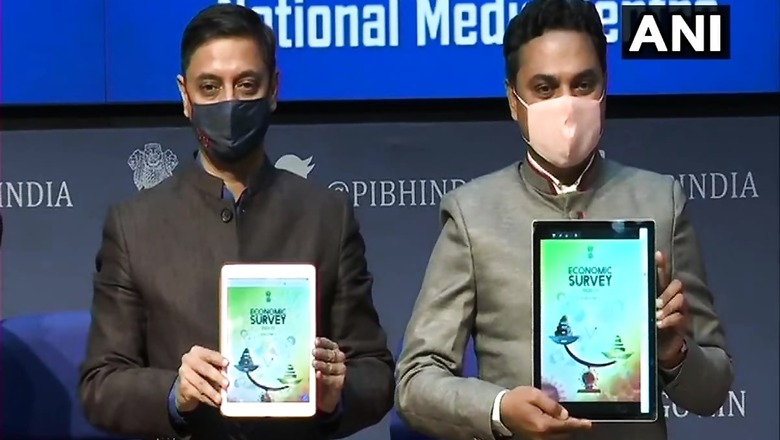

The Economic Survey 2020-21 conceitedly states, “The increase in the size thresholds from 10 to 20 employees to be called a factory, 20 to 50 for contract worker laws to apply, and 100 to 300 for standing orders enable economies of scale and unleash growth. The drastic reductions in compliance stem from (i) 41 central labour laws being reduced to four, (ii) the number of sections falling by 60 per cent from about 1200 to 480, (iii) the maze due to the number of minimum wages being reducing from about 2000 to 40, (iv) one registration instead of six, (v) one license instead of four, and (vi) de-criminalisation of several offences.”

It concludes the paragraph, vainly, that the reforms “balance the interest of both workers and employers.” Incidentally, this is the only paragraph the Survey has actually used the term ‘worker’, other than for ‘knowledge’ and ‘health’ workers in some sections.

The term ‘investor’, however, has been used in the survey in almost all sections in all chapters. Over the period of the last two decades, the economic surveys have had a significant makeover from having worker centric and trade union centric economy debates to now when the debates entirely focus on the interests of employers and investors.

So when the survey declares that reforms ‘balance the interests of both workers and employers’, it is not difficult to understand that the balance is categorically in favour of investors.

The survey later argues, “Despite making huge strides in the overall Ease of Doing Business Index rank, India still lags behind in the sub-categories ‘Starting a business’ and ‘Registering Property’ where the country’s rank is 136 and 154 respectively”.

Even after three decades of deregulations, it complains about the presence of a high number of procedures. It argues for continued deregulation. Incidentally, on the same page, it says that India is ranked 104th in government regulations being effectively enforced; ranked 107th in government regulations are applied and enforced without improper influence; and ranked 101st in the context of percentage of females employed with advanced degrees. For some reasons, these rankings do not find bothering for the survey.

Instead, it has listed the steps the government has taken for enhancing Ease of Doing Business: “Decriminalisation of Companies Act defaults involving minor technical and procedural defaults; Lower penalties for all defaults for Small Companies, One-person Companies, Producer Companies & Start Ups; and Private companies which list Non-Convertible Debentures (NDC) on stock exchanges not to be regarded as listed companies”.

Incidentally, it has also listed the three farm laws as steps to represent accomplishments of the structural reforms. In all this, what is disconcerting is that these ‘successes’ are shown as ‘successful’ government response to the pandemic. It states, “India initiated a slew of multi-sectoral supply-side structural reforms to lend flexibility and resilience to supply chains as a part of the Atmanirbhar Bharat Mission (ANB). India is the only country to have undertaken structural reforms on the supply-side at the initial stages of the pandemic”.

Ironically, while the survey states that the Atmanirbhar Mission is to endeavour to build resilience to supply chains, it does not necessarily seem to reminisce the face of stranded migrant workers belonging to that supply chain for weeks beginning the inglorious lockdown. Does the resilient supply chain not mean the presence of a delighted supply chain migrant worker? If that is so, the survey should have recognised that the basic need for a worker in the supply chain is receiving a living wage, with all social security benefits.

The survey, instead of debating on living wage, quotes a 2016 study to argue that countries with more stringent labour codes are less likely to enforce them, by using the argument, “The stringency of labour regulation (measured as fine for violation of minimum wage) correlates negatively with the intensity of its enforcement (measured as average medium imprisonment for the same)”.

It further reasons, “The over-regulation caused endemic unreliability and defeated the whole purpose of having detailed regulations” citing examples of such inspectors in the developed country (USA) who check particular standards in some places, but neglected in others.

The survey concluded, “The evidence, however, shows that India over-regulates the economy. This results in regulations being ineffective even with relatively good compliance with process.”

The course of the so-called economic reforms for this forthcoming decade is thus well-defined: there is going to be further deregulation of the economy in favour of businesses. It also means, in future, the very institution of minimum wage may not necessarily have formal protection. They may not be removed, but the regulatory infrastructure, such as labour inspection, might become redundant. Do not the farmers fear the same with respect to Minimum Support Price institutions, in the context of new farm laws?

If the survey represents the government analysis of the current status of Indian economy, the most important takeaway from pandemic is that the government can actually not learn even from the pandemic. It also means that there is little surprise element we could expect from the National Action Plan on Business and Human Rights, which is expected to be out in early 2021. The dominance of the need to enhance Ease of Doing Business Index ranking would mean that the government would rather bury any mechanism or institutions that visibilise human rights than to address violations.

The institutions of minimum wage, living wage, minimum support price; and those of collective bargaining, trade unions would continue to be seen as bottlenecks for investments, even though they are embodiments of human rights. The NAP is not going to be created in a vacuum, but amid the struggle between the interests of employers and of workers; of businesses and of workers and communities; of objectives of growth and of redistribution. The survey summarily dismisses the mechanisms of redistribution, when it cites some research to say that rise in the growth of mean consumption was responsible for approximately 87 per cent of the cumulative decline in poverty, while redistribution contributed to only 13 per cent; and concludes, “redistribution is only feasible in a developing economy if the size of the economic pie grows”.

The Economic Survey is entrenched into the government’s so-called structural reforms, in which labor is a commodity; human rights is a risk in smooth functioning of a company; and in which the investor continues to be Superman.

The survey has an elaborate, but convenient, Bare Necessity Index, but if it had empathy for the poor as a necessity for a survey, this surely would rank poor on that. ‘Let us not spend our time looking around for something we want that can’t be found’! This is not Rudyard’s Jungle Book!

Read all the Latest News, Breaking News and Coronavirus News here

Comments

0 comment